Art reviews: SJ Peploe | Alberto Morrocco | John Mackechnie

SJ Peploe: Studio Life at 150, Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh *****

Alberto Morrocco: The Family Archive, Open Eye, Edinburgh ****

John Mackechnie : Shifting Sands, Glasgow Print Studio ****

Advertisement

Hide Ad2021 is the 150th anniversary of the birth of SJ Peploe. The Scottish Gallery is marking the event with a major exhibition, and it has two good reasons to do so: its director, Guy Peploe, is the artist’s grandson and the gallery has shown Peploe’s work since 1903. There was a break in 1913 when he got too modern for the gallery’s director, Peter McOmish Dott, but the relationship was picked up again in 1922. It continued until the artist’s death in 1935 and thereafter until it became a family relationship when Guy Peploe became director of the gallery. Photographs of the artist’s family and friends give the show a family feel, too, but it also roots the artist and his work in the real world.

Peploe was one of the four Scottish Colourists and we speak of them as though they were somehow a unit, but of course they were not. They differed in age and their work is very different too. Peploe was the oldest of the four. JD Fergusson was just two yeas his junior and he and Peploe were close friends from an early date. Peploe and Cadell became close friends, too, but not until much later. Even when they worked side by side, as Peploe and Fergusson often did in France, and Peploe and Cadell on Iona, you would never confuse their work.

Peploe showed his promise early. The Smiling Girl of around 1896, a study of his favourite model at the time, the teenage gipsy Peggy Blyth, is a vivid and accomplished painting. With echoes of Murillo and Velazquez, it also seems a bit old-fashioned. You could say the same of Still Life with Roses from a couple years later, but the inspiration, Manet now not Murillo, is more up to date. There might be a memory of Manet in Peploe’s early masterpiece, The Lobster, too. A red lobster, a yellow lemon, a white plate and an ochre knife handle are all seen against a dark ground. Above them his signature is written vertically in red, looking like a firework against a dark sky. Altogether, the picture has such economical mastery that really it is beholden to no one.

The same is true of The White Dress from a few years later, but the mood is quite different. Painted in Raeburn’s studio, it is a picture about light, but also about life. The picture is so freely painted that the sitter is hardly defined, but shining through swirling brush strokes in cool white, blue and grey, the warmth of her skin, set off by red in her lips and a rose in her hair, makes it seem radiant with life.

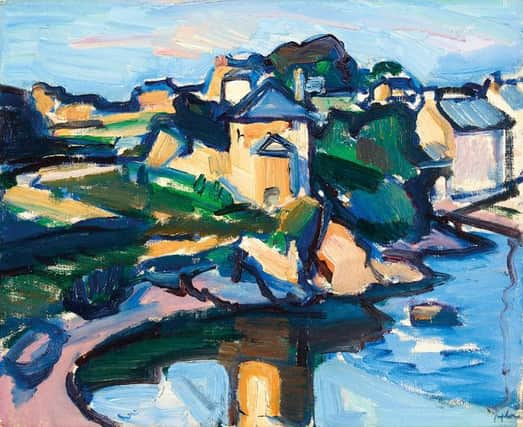

The same vivid freedom is seen in a small painting of Paris Page done working alongside Fergusson in the summer of 1907. Then in 1910, after several summers in France, Peploe, newly married to Margaret Mackay, moved with his new wife to Paris to join Fergusson. That summer the two artists worked together at Royan on the Gironde. Here Peploe produced paintings like Royan Harbour, whose freedom and brilliant colour clearly reflect the recent breakaway innovations of Matisse and the Fauves. Indeed, he painted his wife with bright green shadows in homage to Matisse’s The Green Stripe, one of the most notorious Fauve paintings, though Mrs Peploe doesn’t look too sure about it.

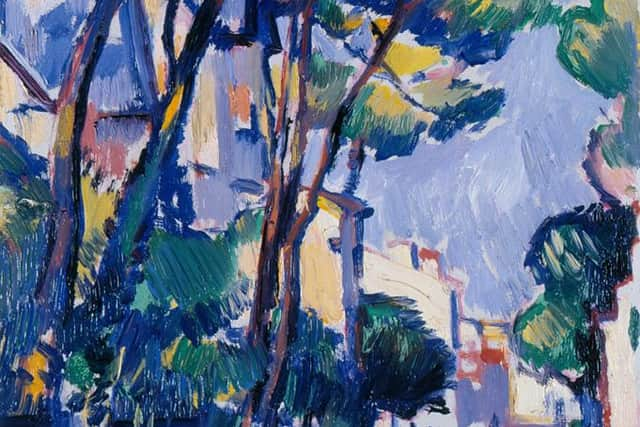

But Peploe was not just a follower of new trends. Already in 1903 he painted a startling picture of Edinburgh from Murrayfield which clearly shows he knew and admired the painting of Van Gogh, whose example was key to the new freedom of the Fauves. Later, though, it was Cézanne who inspired him. A lovely picture done in Brittany in 1911 already shows his understanding of Cézanne’s painting. Some ten years later, too, working alongside Cadell, he painted The North End, Iona. The picture, with its colour shifting subtly between warm and cool and its open, deliberately unresolved lines of drawing is pure Cézanne.

Advertisement

Hide AdUnlike many of the Provençal master’s imitators, however, Peploe clearly understood what he was driving at and in the latest picture here, a painting of dark trees in Perthshire from around 1933, he has built on Cézanne’s example to create a solemn and beautiful image. There is not a still life here from such a late date, but Pink Roses in a Glass Vase shows the same grasp of the mysterious magic of Cézanne in the balance he strikes between certainty and uncertainty. We look at what Peploe has painted and know at once that he has made something permanent and resolved, but has somehow at the same time incorporated into it our knowledge of life’s mutability. This is what Cézanne achieved, but very few of his followers, including his great champion Roger Fry, really understood, let alone were able to emulate it as Peploe has done here.

Peploe was a superb draughtsman and there is a lovely group of drawings in the show to prove it. There is likewise a group of fine drawings in Alberto Morrocco’s show at the Open Eye and their command of drawing links the two artists. It seems effortless, but it was taught. Drawing was once the bedrock of art education and they learnt it in the same tradition. There is, for instance, a lovely drawing by Morrocco in chalk and charcoal on tinted paper of his wife Vera sewing. It is precisely seen yet alive. A sketchy drawing of a mother and child has a Renaissance feel to it and so shows his debt to master draughtsman James Cowie. He was very much his own man, however, and there is a casual ease about a drawing of washerwomen in Anticoli, for instance, which is as charming as indeed the artist was himself.

Advertisement

Hide AdBut for all his informality, there is always a sense of structure in his work and it informs paintings here like a still-life with fruit, or a red field seen through a screen of vines. The show is called Alberto Morrocco: the Family Archive, however, and it is the family pictures that stick in one’s mind, that drawing of Vera, a beautiful painted portrait of her, or a drawing of his son Laurie as a small child.

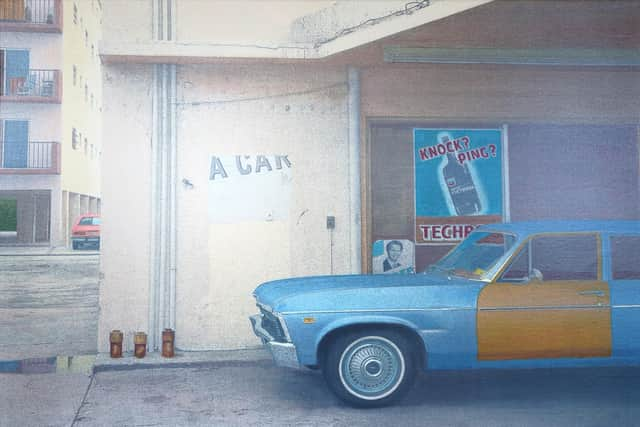

John Mackechnie has for many years led Glasgow Print Studio as its director, but he has never stopped making prints. He was to have had a show in the Studio for his 70th birthday, but after Covid delays it is now a show for his 72nd. He has made good use of the time in lockdown to produce a series of striking paintings on a favourite theme, American urban landscapes, populated by his signature, nostalgic vision of vintage American cars. But he is of course also a master printmaker and the show includes some really beautiful screenprints of water. It is transparent, looking into sunlit shallows and seeing at once surface and depth, or it shimmers with nighttime reflections. All very beautiful.

SJ Peploe and Alberto Morocco until 23 October; John Mackechnie until 20 November

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions