Art reviews: Sam Ainsley | Research + Practice | Henry Fraser | Kirsty Wither | Jana Emburey

Sam Ainsley: Stories Real and Imagined, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh ****

Research + Practice, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh ****

Henry Fraser, Keep the Heid, Open Eye, Edinburgh *****

Kirsty Wither, In Colour, Open Eye, Edinburgh ****

Jana Emburey, Elemental, &Gallery, Edinburgh ****

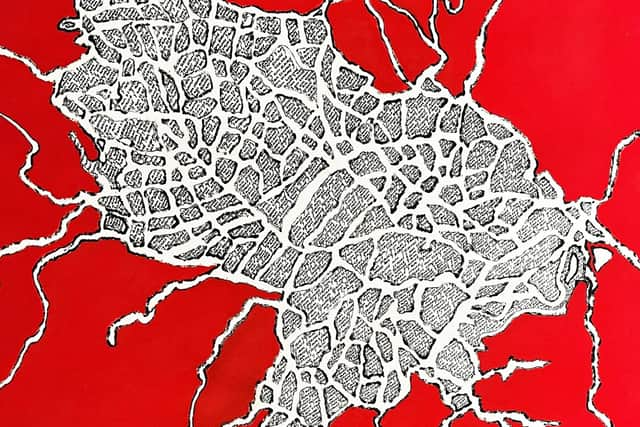

If you could conceivably imagine the view of the neighbouring atomic or sub-atomic world enjoyed by a single electron, it might well resemble our view of the stars in the night sky, and the macroscopic and microscopic do sometimes have a strange affinity. Their unequal symmetry is one starting point for the art of Sam Ainsley, and indeed in her show at the RSA Academicians’ Gallery, Stories Real and Imagined. She says she is “fascinated by the relationship between visual images of the ’micro’ and the ’macro’” and in the show there is a painting called The Milky Way that suggests just such a connection between the microscopic world below and the starry heavens above. Two prints entitled Scotland’s Waterways 1 and Scotland’s Waterways Doubled also demonstrate what she means. In them she has taken a simplified map of Scotland’s rivers and then repeated it in a mirror image. Going from geography to biology, the result is still clearly an image of Scotland, but it also resembles the two hemispheres of the brain with the waterways suggesting the patterns of its interconnecting fibres.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn a similar way, another print titled The Darkened Splinterecho Brainstream Tide suggests at once the organic matter of the brain and an aerial view of a river among hills, while Interior/Exterior seems to shift from an image of a hand and arm through diagrammatic veins, to a partial outline of the sun and a dark, starry sky. It is a poetic idea to suggest such an analogy between the natural world, the human body and indeed the human condition. At times it is her own condition too, and her perspective as a woman artist. Her Wild Scared Heart is a circular painting of something that could be at once an aorta and a tree, but tucked within it is a heart transformed into a scarlet flower. In The Ribcage Flower and the Blue Dress, a scarlet ribcage on a stem like a flower sits alongside abstract folds of deep blue velvet.

A print called Homage to D'Arcy Thompson, apparently an abstraction of the intricate patterns organic growth, also points to part of her inspiration. Thompson was a polymath. Professor of natural history at St Andrews University, he is described on the university website as the first bio-mathematician. His great book On Growth and Form published in 1917 described the logic, the beauty and mathematical symmetry of the dynamic processes that shape the natural world. Ainsley’s Worlds within Worlds is composed of a honeycomb pattern of hexagons, each suggesting different forms of cellular growth, and so does seem directly to explore Thompson’s analysis of structure in nature. He has been an inspiration to many leading artists, but his book has also been widely influential in modern art education, a field in which Ainsley has herself also been prominent.

The RSA lower galleries are adjacent to the Academicians’ Gallery and in them Research + Practice shows a selection of the work of six artists who have recently enjoyed support from the Academy’s programme of grants and awards. Since its inception in 2009, we are told, this programme has disbursed £313,000 to 106 artists. A really significant contribution to the visual arts in Scotland, it has supported both established artists and others at the beginning of their careers.

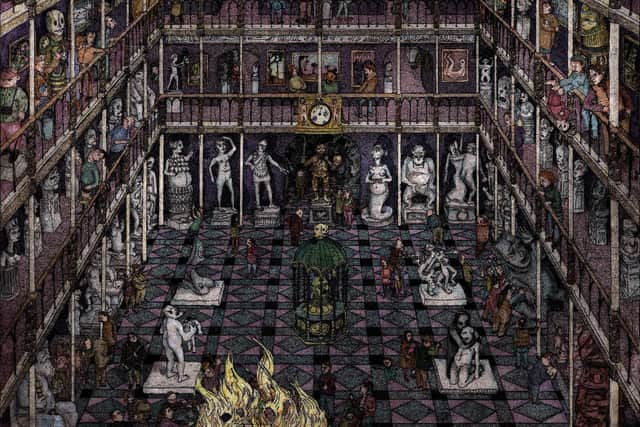

Among those showing work, Robert Powell, for instance, is a well-known printmaker. He has had a residency at WASPS in Shetland supported by the RSA. He went there, he says, to think about “how objects haunt us” – not in the ghostly sense, he assures us, though that happens often enough in his art – and correspondingly to unclutter himself and, he says, his own “cocoon of objects was scraped away.” Not that his prints show it. The Library of the Blind, for example, is a wonderful, phantasmagoric variation on the Tower of Babel, while The Work of the Dead is a crowded, multi-storey prison-like interior. Both are gloriously cluttered and repay endless investigation of their extraordinary details.

Powell’s bizarre world finds an echo in the work nearby of Flore Gardner who has used a residency at Edinburgh Printmakers to learn to etch and has put her new skill to good use in a set of images every bit as strange as his. There are echoes too of Sam Ainsley’s metamorphic imagery in her prints as arms and legs and breasts ramify into strange, compound creatures, half-human half-vegetable. She touches the truly bizarre, however, when she creates a headless torso with an open mouth in its belly, or a row of headless torsos strung up like butchered carcasses with macabre inscriptions such as “the dead can wait” written on them, while another print is just an overall pattern of disembodied eyes. It is all thoroughly surreal.

Among the other artists whose work is included here, Samantha Clark, awarded the William Littlejohn prize for excellence and innovation in water-based media, has respected the prescription of her award but in a technically inventive way to create paintings that are broadly abstract but suggest the sea. Meanwhile, working in the RSA Collections, by ingenious research Victoria Bernie has restored the name – Elizabeth Maria Ouchterlony – to an early 19th-century artist represented in the collection but hitherto only known baldly as Mrs Cumming.

Advertisement

Hide AdAt the Open Eye Gallery, the strain of dark surrealism seen in Flore Gardner and Robert Powell’s prints finds an echo in Henry Fraser’s show Keep the Heid. Mostly paintings of single heads, but so roughly executed and so little defined that they can hardly be called portraits, they nevertheless have striking individuality, each one a distinct and haunting presence. They reflect, he says, human fragility and resilience during these times of global chaos and uncertainty.

His sitters certainly seem haunted. Brother is a white-faced figure. A halo and a small cross suggest a religious brother rather than a sibling, but his religion doesn’t seem to offer him much comfort. Encore is a roughly painted skull with spooky black holes for eyes. Inferno, an exception among the heads, is a flaming sky with terrified figures massed beneath it. Perhaps the painting that best encapsulates it all, however, is Perfect Storm. A dark figure against a dark sky with a snowstorm whirling round his head seems nearly blown off his feet by the wind. It is an icon for our times.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Give me an ounce of civet; good apothecary. Sweeten my imagination”, says poor blinded Gloucester in King Lear, and also at the Open Eye, Kirsty Wither’s show In Colour does just that. Not that it is simply sweet. A laden brush and palette knife give body to her pictures. Consequently the colour in a painting like Lemons in Luxury, for instance, or in flower pictures like Fruit and Roses, is rich, but it is much more than decorative. On the contrary, her pictures have a very satisfactory kind of poetic solidity.

Round the corner at the &Gallery, in Jana Emburey’s show, Elemental, paint matters too, but in a very different way. She has revisited abstract expressionism in a series of elegant paintings carried out with freely handled paint on unprimed canvas, or absorbent Japanese paper. The balance she strikes between freedom and control is quite perfect.

Sam Ainsley and Research + Practice until 2 October; Henry Fraser and Kirsty Wither until 24 September; Jana Emburey until 28 September