Art reviews: Robert Powell | Patricia Paolozzi | Lily Macrae | John Byrne

Robert Powell and Patricia Paolozzi Cain, Kilmorack Gallery, by Beauly ****

Lily Macrae: Reverie, &Gallery, Edinburgh ***

John Byrne: Selected Prints, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh ****

Advertisement

Hide AdAt a meeting of art historians in in London many years ago, as the venue for the next gathering was discussed the late Andrew McLaren Young, professor of Fine Art at the University of Glasgow, volunteered Glasgow. To which the plaintive reply was, ‘but it is so far away.’ To this shameless demonstration of metropolitan provincialism McLaren Young’s robust riposte was, “It depends where you start from.”

Remote is not just geography, it is an attitude of mind. Around Scotland there are a good many galleries that might be regarded as remote according to this same small-minded geography, but which flourish nevertheless. The Pier Art Centre in Orkney, An Lanntair in Stornaway, or Taigh Chearsabhagh Museum & Arts Centre in Lochmaddy are just some examples of art institutions flourishing a long way from the notional centre of things. Like most art institutions, they inevitably struggle for funding, but to endeavour to make your livelihood running a commercial gallery showing serious art far from the centre is a challenge of a quiet different order. Nevertheless there are galleries that do just that. The Kilmorack Gallery outside Beauly is one notable example and Rhue Fine Art, on a beautiful site by the sea, west of Ullapool is another.

The Lost Gallery in Upper Donside, more or less on the eastern slopes of the Cairngorms and so remote that it was occasionally cut off by snow, was even more remarkable. It was founded by artist and illustrator Peter Goodfellow and his wife Jean and defying every possible metropolitan assumption was run by them with notable success for almost thirty years. Sadly though Peter died in December and from earlier this month the gallery will be closed till further notice.

There are certainly others too, like the Smithy Gallery in Blanefield for instance, and Brown’s Gallery in Tain, both marginally more ‘central’ as they are actually in places, but these reflections were prompted in particular by a visit to the Kilmorack Gallery. It was the brainchild of Tony Davidson who still runs it. He opened it in 1997 after a battle with the planning authorities over whether an art gallery was an appropriate use for a beautiful Georgian church. Now you cannot imagine how there was ever any question. On the road from Beauly to Cannich, or indeed to Glen Affric, but nowhere else, it is certainly one of the most beautiful galleries in the country, central or remote. There is always a range work on show there and currently the featured artists are Robert Powell and Patricia Paolozzi Cain.

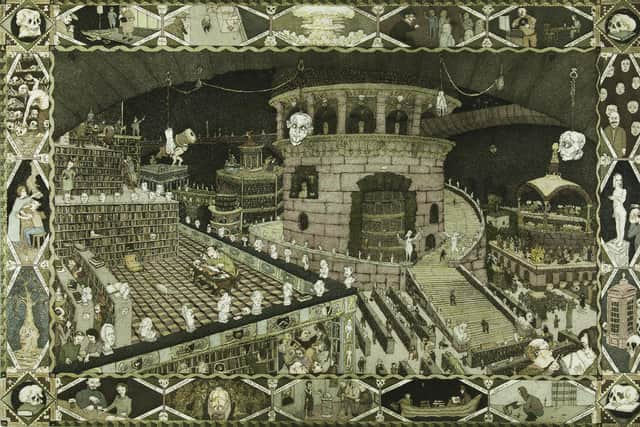

Robert Powell’s phantasmagorical prints are familiar and there are a number of them here including his particularly complex, many-figured etching Library of the Blind or Memory of Babel. It is like something from Bosch or Brueghel, a vast library where the rotunda that used to be the heart of the British Museum Library, where Karl Marx once sat and thought, seems to have been crossed with Breughel’s Tower of Babel. In keeping with the latter image of confusion and doomed aspiration, however, it is a library of books that no one can read.

Powell’s painted work is less familiar, but a painting called Supper, small in size but not in presence, is a fine example. Twelve grotesque people behind a long table laden with weird looking food caricature Leonardo’s Last Supper much as Luis Buñuel did in the spectacular climax of his film Viridiana with a line-up of beggars, grotesque as those in Burns great poem The Jolly Beggars.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn April, Rhue Fine Art, currently showing Linda Lashford’s beautiful photographs, will show Two Ravens, a remarkable animated film that shares something of the same grotesque aesthetic as Powell. The film is a collaboration between animator John McGeoch, painter John Slaven and musician Christine Martin.

Meanwhile, back at Kilmorack alongside Powell, Patrica Paolozzi Cain’s work depends on drawing. Indeed coloured pencil seems to be her favoured medium. She uses it to create intricate tangles of lines and the result is like looking into a hedgerow, or thicket of tangled growth. She titles two of them Maps, but if they are really maps of anything it seems to be of the intricate connections of thought and the mind’s processes.

Advertisement

Hide AdRemote of course has changed its meaning since these pioneering ‘remote’ galleries began business. Online sales have altered the economy of art in the centre as well as further afield. At &Gallery in Edinburgh, I was told how through the internet the gallery can sell work to people a very long way from Dundas Street where, like so many of Edinburgh’s galleries, it is located. The current show there is Reverie, the debut of artist Lily Macrae.

A small group of rather lovely abstract paintings are made by brushing on paint and then wiping it away to create transparencies and sweeping marks. The artist has evidently then moved on to find faces in these patterns. They seem mostly to be of children whose features catch the light as, close together, they engage in some mutual, childish amusement.

Also back in that part of the world that likes to think of itself as the centre of things, at the Academicians’ Gallery in the RSA, Robert Powell’s dark fantasies again find a certain echo in a selection of John Byrne’s prints. Though Byrne’s vision is not quite so dark as Powell’s, the two artists do share a certain ironic detachment.

Byrne’s irony, though, is often directed at himself. His self-portraits are numerous. There are several even in this small selection of his prints, but nobody could accuse him of vanity. In the screen print Red Kerchief, for instance, his face is gaunt as he squints sideways at us. In images like this, it seems that he is puzzling, just as David Hume did, over where the self could reside in what Hume called a “bundle or collection of different perceptions, which succeed each other with an inconceivable rapidity?”

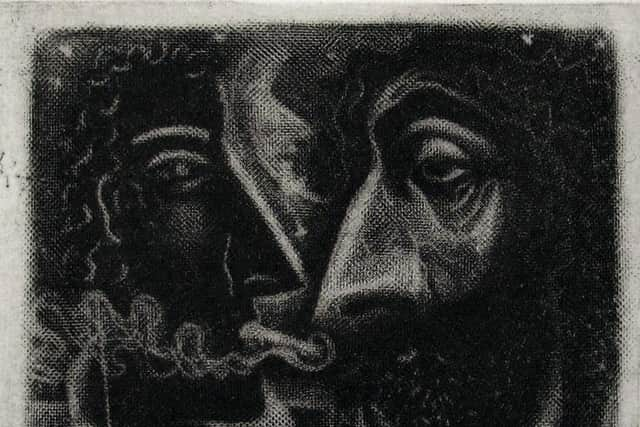

Byrne is a polymath and seems to work effortlessly whatever medium he chooses to deploy, or indeed whatever style —- Still Life with Guitar here is an accomplished essay in Cubism —- There are etchings, screen prints and mezzotints here and they range in date from 1992 to 2020. The latter technique is a way of engraving in tone not line and one of the most striking images here, Young Smoker, Old Joker, is an example of its unique qualities. Two shadowy faces close to each other are joined by an elegant curl of smoke, while the moon, perhaps the old joker in the title, looks on.

Robert Powell and Patricia Paolozzi Cain until 28 February; Lily Macrae: Reverie, &Gallery until 1 March; John Byrne until 5 March