Art reviews: Robert Powell | Made at Castle Mills | Kevin Harman

Robert Powell, New Work, Kilmorack Gallery ****

Made at Castle Mills, Edinburgh Printmakers ****

Kevin Harman, Ingleby Gallery, Edinburgh ****

Wikipedia tells us that a Phantasmagoria was a form of horror theatre that used magic lanterns to project frightening images such as skeletons, demons, and ghosts onto walls, onto smoke, or onto semi-transparent screens, typically using rear projection to keep the lantern out of sight. The article has a helpful illustration from a nineteenth-century French book on optics showing people in regency costume recoiling in horror from a ghostly skeleton projected on the wall of a gothic interior. The dictionary is more succinct and defines a phantasmagoria as ‘a sequence of real or imaginary images like that seen in a dream.’ It seems to me that both accounts fit, as nothing else would, Robert Powell’s remarkable prints, though of course he doesn’t use a magic lantern, but an often intricately worked etching plate. A bit of magic is often added, however, when his prints are tinted with watercolour.

Appropriately to this theme too, in Powell’s online show on the Kilmorack Gallery website one of the most extraordinary of a number fairly extraordinary prints is titled Phantom Things. A metre long by just nine centimetres high it is a phantasmagoria in seven parts, or rather in seven adjoining rooms in a cutaway view of a building. At the left-hand end, ghoulish figures are cramming into a monstrous mouth. Then there is a bedroom and a figure half out of the window with a Fuseli-style incubus on his or her back while, by the bed, a man embraces a woman with a skull on the end of her serpentine neck. Next door in the kitchen, a hideous cook is about to put a large pod bursting with humanoid peas into the oven. In the bathroom, hands reach up out of the toilet to grab a naked figure attempting to sit on it. And so it goes on, with a great deal more detail on the way, until at the right hand end a group of grinning bogles peer back gleefully along the line of rooms.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe title of Cenotaphia or the Bone Shakin’ Finger Snappin’ Skull Claspin, Halligarnassan Fun Park of Mausolus is almost as long as the print Phantom Things, but this print is actually square. Citing the Cenotaph and the tomb of Mausolus at Halicarnassus, which gave us the word mausoleum, the subject seems to be a cemetery theme-park, or a fairground of the dead. There is a big wheel and a graveyard ghost train and much else all within a border of gravestones. The Stone Web continues this macabre theme with a cutaway view beneath a graveyard of the winding tunnels of a labyrinthine catacomb where a population of skeletons carries on life or afterlife as normal.

There are simpler images too, however. The Staircase shows a frightened man on a long staircase in a gloomy house watched by ghouls below and ghostly portraits above. The Grey Wallpaper is a plain interior with patterned grey wallpaper, a sick bed (or a death bed) and a rather melancholy couple. A charming oddity here, really a sculpture not a print but print-derived all the same, is a box made from used etched plates in the shape of a gothic reliquary. Adam and Eve are visible on one side, a pair of skeletons on another. A very long title tells us that it is indeed a reliquary, not for a saint’s bones, but for a mobile phone and all the photographs and memories it took with it to the grave.

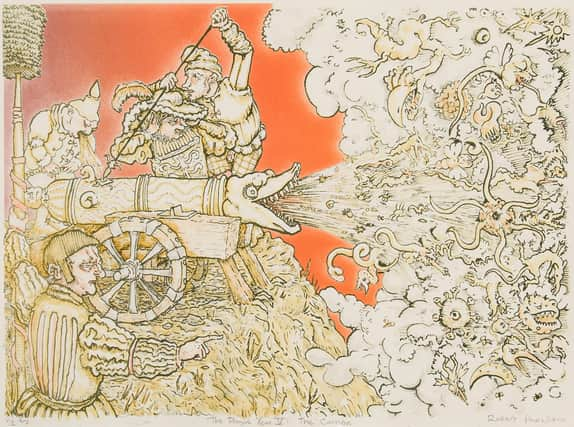

The Invisible Hand, if obliquely, is more topical. It takes a swipe at market-led economics as the invisible hand of Adam Smith’s socio-economic metaphor reaches out to the darkness to grab him. A small group of plague pictures about the Plague Year is even more topical though. The Plague Year 1 shows figures in the hideous bird masks of 17th-century plague doctors attending a man with Bubonic plague while figures with the masks our present day plague peer out form beneath the bed. In The Plague Year II, The Annunciation, the usual figures of an Annunciation are replaced with a bird-masked plague doctor and a modern woman clutching herself in pain. In Plague Year III and V, we are back to Phantasmagoria. In the former, one of the four horsemen of the Apocalypse rides out, backed by a crowd of monsters. In the latter, a dragon-headed cannon manned by 16th century soldiers spews a cloud of horrors that includes the too readily recognisable coronavirus. Finally, on the same theme, I think, in Revenant City an ominous black cloud overs over an island city. These are images for our times indeed.

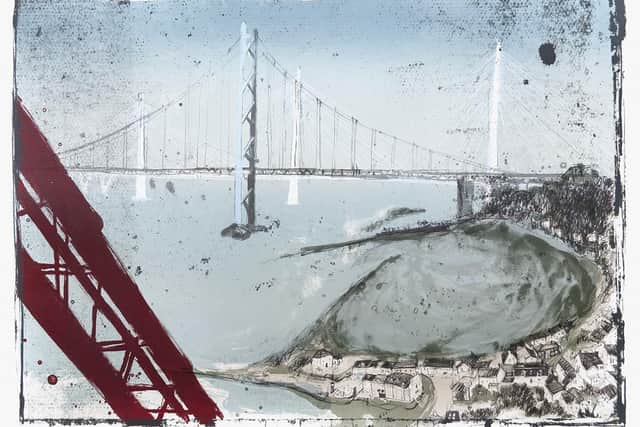

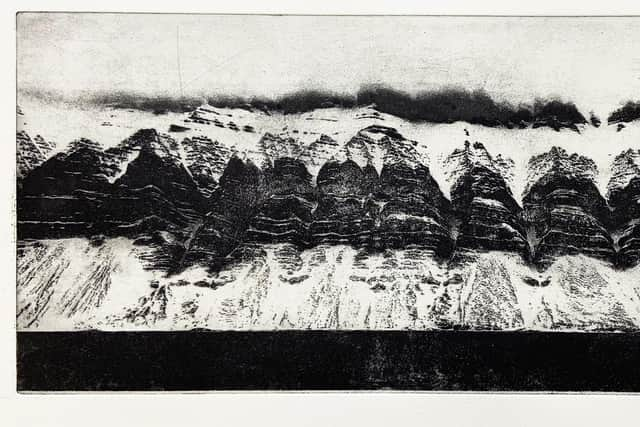

Robert Powell works at Edinburgh Printmakers and so is also included in the current EPS members’ show, Made at Castle Mills. Powell’s contribution is Clod King, a man with a stick and paper crown standing on the Bass Rock like an enigmatic giant. Including 20 artists, this show is pretty diverse. Appropriately for a state of the art workshop such as EPS now is, the skill and variety of the techniques is striking. Mary Walters’ Svalbard Mountain, for instance, is a sombre cliff of ice and snow, probably in the original no more coloured than this stark black and white photo etching. Very different, Rona MacLean’s beautiful Birches Blue, mixes flat screenprint with blind embossing so that parallel birch trunks range across the paper, first in white relief and then in gentle blue. Joyce Gunn Cairns' The Pedigree of Honey, a delicate drawing of a bee in screenprint, takes its title from Emily Dickinson and quotes her alongside the image. Joy Arden’s Untitled uses collagraph, effectively a print from a collage, to create a quasi-musical grid of simple verticals and horizontals. Equally abstract with a pattern tangled lines, Alison Grant’s For You is lithograph in intense blue against near black. John Heywood’s Royal Mile in the Rain is a fine etching in the classical tradition of ES Lumsden who, appropriately, long ago played a key part in establishing the vigorous, craft-based tradition of Scottish printmaking so well displayed here.

At the Ingleby Gallery, Kevin Harman uses household paint on double glazing units to create rather striking abstract pictures. I am always suspicious of artists using household paint. It is a bit of statement: “Don’t think I am an ordinary artist using oil paint like some stuffy old master,” is the sentiment it suggests. In Harman’s case, however, the texture, density and viscosity of household paint do appear to make some sense.

I have to say, though, that this business of having to look at art online has serious limitations and I do feel them very strongly with Harman’s work. Density, transparency and other more intangible things simply get lost reduced to binary code.

Advertisement

Hide AdRobert Powell until 25 February, www.kilmorackgallery.co.uk; Made at Castle Mills until 28 March, www.edinburgh printmakers.co.uk; Kevin Harman until April, www.inglebygallery.com

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions