Art reviews: Reduct and Stuart Duffin at the RSA | Robert Powell at the Fine Art Society | Fiona Finnegan at Arusha Gallery

Reduct, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh ****

Stuart Duffin: Peace Starts with a Smile, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh ****

Robert Powell, Phantom Things, the Fine Art Society, Edinburgh *****

Advertisement

Hide AdFiona Finnegan, Midnight Candy, Arusha Gallery, Edinburgh ****

In 1951, the Arts Council put on an exhibition called 60 for ’51 to complement the Festival of Britain’s vision of a new and modern Britain with a bit of modern art. William Gear won a £500 purchase prize with Autumn Landscape, a painting that in spite of the title was completely abstract. It caused a furore. The pages of the Telegraph and Mail almost self-ignited with readers’ rage. Abstract art had been around for nearly 50 years, but the British public were not in tune with it. Prefiguring Brexit, after the Second World War anything that looked foreign was suspect and Gear had gone straight from war service, latterly as one of the monument men, to Paris. There he had joined a new, Continental avant-garde. Alan Davie, catching up on a traveling scholarship delayed by the war, visited him and was introduced to the new abstract art. Before the war, abstraction had been cool and decorous. This art was wild and anarchic. Gear and Jackson Pollock exhibited together in New York in 1949 and Davie then encountered Pollock’s work in Venice. He never looked back.

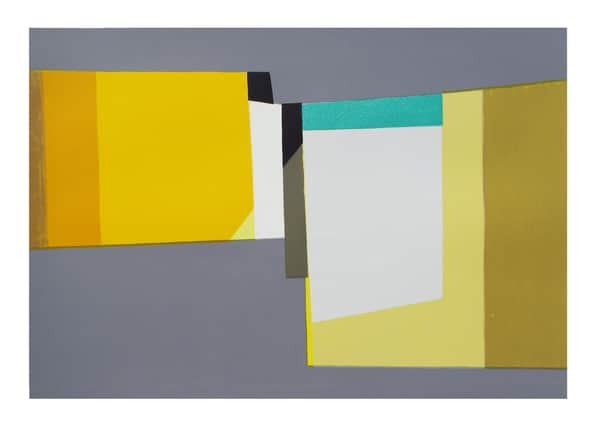

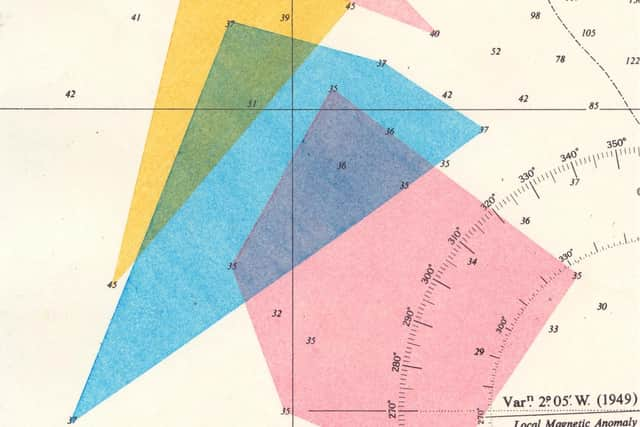

Now, with a single, slightly tame picture, Davie features in Reduct, an exhibition devoted to abstraction in Scottish art at the RSA. Like Gear, who is not in the show, Davie became an abstract expressionist, a gestural painter of subconscious moods and images. But Reduct, we are told, focuses on a more intellectual abstraction, “the pursuit of non-objective form, through the prism of geometry.” What we would expect then is not Davie, or even Paolozzi, who is also here with a small work from the sixties, but an art that is austere and ordered. Ultimately idealist, the kind of geometric art that this suggests goes back to the Bauhaus and de Stijl. It deals in an imagined order, unsullied by the imperfection of our sublunary world. (Sublunary because it was once supposed that above us, the moon and planets moved in a perfect, immutable order, the music of the spheres.) There are certainly some examples of this kind of imagery here. Joe Ganter’s prints, overlapping geometric shapes in blues and greys and greens with no hint of any expressive intention, do look back to Bauhaus experiments with geometry and colour. With a set of three pictures composed of concentric squares, Rhona Taylor also pays homage to Josef Albers, one of the masters of this Bauhaus abstract geometry. (Jim Lambie similarly paints brilliantly coloured, concentric circles, but then subverts this idealist proposition with an unruly dribble of red paint.) In a similar visual language, the complex perspectives of Bronwen Sleigh’s prints suggest an ideal architecture of the mind.

But then there are two small works by the late John McLean. He was certainly an abstract artist all his life and one of the works here is composed of interlocking shapes, but geometry was a long way from his mind. "Like singing, like dancing,” was a simile he used for his art. It is purely intuitive and rooted in the world we live in, not in some abstract realm beyond. The same is true of Philip Reeves. One of the most beautiful works here is his Complementary Stacks, two sets of 25 squares, split diagonally with colour above, black and white below. The left-hand group are hard-edged, the right-hand softly brushed. It is pure visual poetry, but the title still refers to the stacks along the cliffs of the north east coast which were an early inspiration to the artist, to landscape in fact. (The interlocking shapes of Katie Schwab’s patchwork quilts are also beautiful, but they are something else altogether.)

Indeed, given the simplicity of the original premise there is a lot of variety here. John Houston once told me how in the 1970s pressure to turn to abstraction was such that he almost gave up painting. Others did yield to fashion and there are abstract works here from that time by Jack Knox and Ian McCulloch. But these works are outliers. Both artists soon abandoned the experiment. Arthur Watson sticks more closely to the exhibition’s premise with Geometric Moonpath, an assemblage of screenprints arranged to suggest moonlight on water. Outstanding here and also close to the original premise are a beautiful diptych by Paul Furneaux called Salt, and Multi-Coloured Chart 38 by David Batchelor, four blobs of poured glossy blue paint stacked vertically. Most intriguing however is Toby Paterson’s Messedamm, an elegant aluminium relief articulated in simple blocks of colour and texture. Stylistically it takes us back to the geometric style favoured for the Festival of Britain. It goes deeper though. Messedamm is an extraordinary underpass in Berlin constructed in 1936 at the height of Nazi roadbuilding. If anything continental, and even more anything German, was unacceptable, was the utopianism of the Festival of Britain nevertheless actually linked to ideas current in Nazi Germany? As Paterson so eloquently proposes, in their ebb and flow, the tides of art are indeed complex and often unexpected.

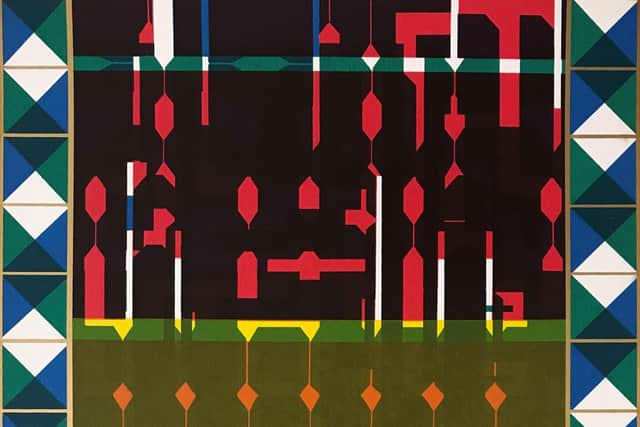

Also at the RSA, Peace Starts with a Smile by Stuart Duffin is an extended visual soliloquy on contemporary Jerusalem. Ultimately this show, too, goes back to the post-war years and to what the Palestinians call the Nakba, the Catastrophe, when in 1948, they were driven from their homes in Palestine by the creation of Israel. The terrible wound has never healed and much of Duffin’s work is a plea for peace and reconciliation. His rich and complex prints bring together imagery of the ancient city of Jerusalem and indeed of Babylon where the Jewish people were themselves once in captivity. There are doves of peace, angels and images of war. The work is a reflection on the complexity of the situation, but also an appeal for its peaceful resolution. Particularly striking too is Still Dreaming of Jerusalem, a collaboration in film and music between the artist and the composer Malcolm Lindsay.

Advertisement

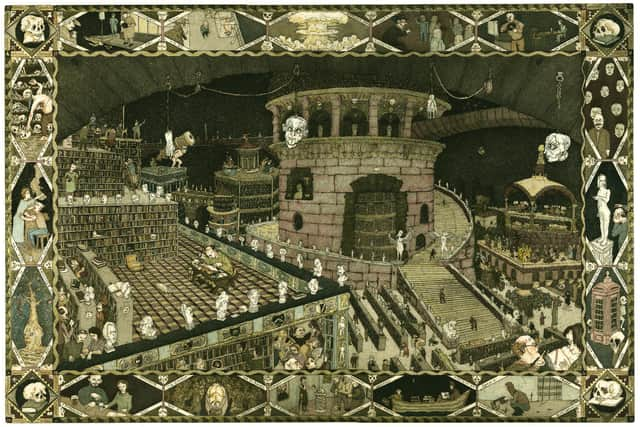

Hide AdThere are some similar themes, but an altogether different mood in Robert Powell’s Phantom Things at the Fine Art Society. The minute complexity of Powell’s prints is astonishing. So too is the dystopian vision they portray. Library of the Blind or Memory of Babel, for instance, takes its theme of the building of the Tower of Babel from Peter Brueghel, but Powell’s Babel is buried deep in one of Piranesi’s Carceri, his dungeons. In another print, Label, Babel is literally inverted, the Babylonians, (the modern Babylonians, I think) are not building a a tower, but digging a huge hole. In The Hole in the Ground, ten grotesque faces peer down into the eponymous cavern. There is much else, and throughout the quality of the printmaking is superb. Grisaille 1: Old Hamlet, for instance – what would Hamlet have been like if he had lived into old age? – is in etching and aquatint, finished in watercolour, and the richness of effect is really striking. Throughout, Powell's macabre vision recalls the grotesque, but also darkly comic world of James Ensor, another great printmaker.

Meanwhile across the road at the Arusha Gallery, in a show called Midnight Candy, Fiona Finnegan paints a mysterious, twilit world where, for instance, eclipsing the sun, the moon rules the sky, or where owls assemble for The Last Sunset, a world where magic might prevail.

Advertisement

Hide AdReduct and Stuart Duffin until 22 November; Robert Powell and Fiona Finnegan until 21 November.

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

The dramatic events of 2020 are having a major impact on many of our advertisers - and consequently the revenue we receive. We are now more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription to support our journalism.

To subscribe to scotsman.com and enjoy unlimited access to Scottish news and information online and on our app, visit https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions

Joy Yates, Editorial Director