Art reviews: Nat Raha | Christian Noelle Charles | There Is Something In The Way | Makeshift | Kiosk | Synthesis: Beyond the Human

Colonial histories have become such a prevalent theme in contemporary art practice that I wonder how much longer these concerns can claim to be “marginal”. Nevertheless, Edinburgh Art Festival continued its platforming of performance work by marginalised voices with Nat Raha’s epistolary (on carceral islands) (***) on 18 August.

Raha is described as a “poet and activist scholar”, and the starting point for her work, which is a co-commission with the TULCA Festival of Visual Arts in Galway, is prison islands around the world, usually with a colonial connection. After a litany of these names: “Bass Rock, Robben Island, Alcatraz, Spike Island, St Helena…” Raha moves into a reading of an intricate and lengthy poem, delivered as if it were a series of letters.

Advertisement

Hide AdRead with little variation in tone, it seems to accumulate subjects: Covenanters banished from Scotland; white colonial power written in the architecture of Edinburgh; the plans for a £400 million “mega-prison” in Glasgow; and on and on it goes. Occasional sound effects and echoes help make it a little more performative, but the link to visual art seems tangible at best.

While there are many important issues here – and the idea of writing as an act of survival, defiance, resistance has a long and engaging history – the effect is a kind of cumulative levelling: incarceration, rebellion, queer rights, trans rights, police brutality, the Easter Rising, all of them are pummelled into a single diatribe which has all the subtlety of a punchbag. One leaves exhausted, rather than energised or informed.

Christian Noelle Charles takes a different approach to the idea of resistance in her solo exhibition, What A Feeling! Act I (****) at Edinburgh Printmakers. She has transformed the gallery space into a beauty parlour, with plush leather chairs and hot pink decor. In place of mirrors are large format “Gettin’ ready” screenprints featuring five black women artists and performers, Mele Broomes, Saoirse Amira Anis, Alberta Whittle, Cass Ezeji and Sekai Machache, whose voices we also hear on the “radio” speaking in extended interviews about what it means to be a woman of colour working in the arts in Scotland.

The transformation of the space is visually impressive, and the beauty parlour idea has resonance: a place of safety for women to come together, but also a place to prepare a face to meet the world. Screenprinting is a multi-layered process; these images are reflections, but more than that. One feels they are looking at us, looking at them.

The dynamic is not entirely comfortable. Charles conveys the sense of a strong, mutually supportive community, but one from which many viewers will feel excluded. While the audio lets us know what women of colour are up against, the work also embraces the strength of their solidarity. If they are banding together against the world, I wonder where this leaves the rest of us.

There’s a similar sense of female solidarity in There Is Something In The Way (***), in the Basement Galleries at Summerhall, which continues to be as important a platform for eclectic visual art during the festival as it is for performance. This group of women have come together around Edyta Majewska and Gail McLintock’s research on Women, Art & Inequality, about the barriers faced by women artists including age, health, class, race and circumstances. Ninety-one per cent of female creatives they spoke to “have had their progress in the arts affected by inequalities”.

Advertisement

Hide AdThus far, it’s awareness-raising. But, in response, the women make art. Lubna Kerr, best known as a performer, makes an installation about the catastrophic flood which destroyed her home. Eleanor Buffam, an artist, writer and musician living with chronic illness, uses cyanotype images of herself, multiplied and mirrored, to create kaleidoscope patterns. Majewska uses miniaturised family photographs to create a beautiful, complex wall sculpture best viewed with a magnifying glass (which is provided).

The barriers they face become grist to the mill of creativity. This, and the sense of female solidarity, leaves one feeling positive despite the issues they have highlighted. Art is struggle, yes, but art is healing, too.

Advertisement

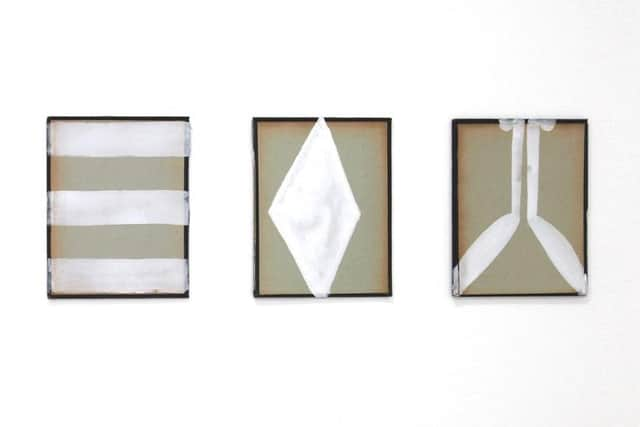

Hide AdIn the War Memorial and Sciennes Galleries, three artists let their work converse around a style they are calling “lyrical minimalism” in Makeshift (****). There is an astonishing harmony between the work of Nicky Hodge, Paul Keir and Alan Shipway in its delicacy and its experimental, provisional nature. Hard-edged ideological minimalism this isn’t – it’s work which happens between the hand and the eye; a suggestion, a question, an improvisation, not a statement.

The works echo one another in colour and form: Keir’s painted wooden objects displayed in open vitrines, Hodge’s small, softly saturated tonal paintings and Shipway’s (slightly) more formal paintings. The similarities between them also accentuate the differences, just as the gestures become foregrounded: the specific texture of a brush stroke, for example.

Where the show falters a little is with the larger scale works in the War Memorial Gallery. The provisionality, the unfinishedness, which is intriquing on a small scale, works less well when made large, as if it can’t quite justify taking up a larger space with a hesitant gesture.

Meanwhile Kiosk (*****) by Charlie Stiven, programme director for painting at Edinburgh College of Art, feels simply unique. Stiven’s rigorously constructed model kiosks are ideally suited to the glass cases of the Lab Gallery.

They are inspired by kiosks all over Europe – simple street architecture used to sell newspapers or coffee – but are not exact copies, more like amalgams and inventions which speak to shifting economic and political circumstances. All are boarded up and abandoned as if infrastructure were collapsing in the face of an uncertain future. A list of works at the end explains the background to each, but it would have been ideal to have this on a handout to read while looking.

Each kiosk has a different story. Grab’n’Go is about the evils of fast food. Happy Days is an art deco-style diner modelled on a refreshment kiosk near Athens, built in the 1950s when American influences arrived in Greece. Farmacia is about the selling off of bits of the Spanish healthcare system, perhaps not entirely legally.

Advertisement

Hide AdBest of British is an end-of-pier kiosk plastered with a peeling union jack. The pier leading to it is cut off, leaving it marooned in Brexit isolation. The accompanying text says it is about the high proportion of Brexit voters in British seaside towns, but it reads like a down-at-heel epitaph on Britishness itself.

Particularly evocative are the three dark kiosks from Lviv, with their Austro-Hungarian-art-nouveau-meets-functional-Soviet design. It’s the story of Ukraine encapsulated in a kiosk, right up to the present day: black debris strewn around suggests the presence of war.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe kiosks have a kind of small brilliance, containing big ideas in a way which is graspable, all wrapped up in a geeky model-railway-building charm. The detail is immaculate, right down to a paper pizza still in its box, a poster for the Ken Dodd Happiness Show. It’s one of the best things I’ve seen this festival.

Synthesis: Beyond the Human (***) is a more difficult show to grasp. Curated by Scott Hunter and Sam Chapman, it features four artists who have participated in a collaborative programme: Danielle Macleod and Oana Stanciu from Scotland, Gak Yamada and Yuichiro Higashiji from Japan. Their work seems to coalesce vaguely around ideas of ritual and spirituality; each practice includes photography.

Each artist has a room for their own work, and then in a final room they show work together, including a handful of collaborations. Macleod’s “wearable sculptures” made from antlers and buzzards’ wings are impressive, both in the flesh and in photographs. Stanciu’s filmed performances evoke everyday rituals, but more impressive still are her photographs which look like they’ve come straight from a surrealist experiment in early 20th-century Paris.

Yamada makes rather beautiful photocollages with broken fragments of who knows what, viewed with a torch in a darkened room. Higashi makes sculptures of mountains by slicing through bound volumes of paper and photographs them. All are interesting, but the dialogues feel tentative, uneasy. One suspects the collaborative element of this project is about process and learning, and is of greater value to the artists themselves than it is to the audience.

Christian Noelle Charles until 17 September; Summerhall shows until 24 September