Art reviews: Jeremy Deller | Cathy Wilkes | Drink in the Beauty | Khvay Samnang

Jeremy Deller: Warning Graphic Content, Modern Institute, Glasgow *****

Cathy Wilkes, Modern Institute, Glasgow ***

Drink in the Beauty, GoMA, Glasgow ***

Khvay Samnang: Calling for Rain, Tramway, Glasgow ****

Jeremy Deller is one of those artists who is a genius at the encapsulation of an idea, a mood, a moment, whether that’s on a billboard the size of a wall or in a large-scale participatory project. The first ever survey show of his prints and poster works, happening simultaneously in Scotland and in Paris, makes this abundantly clear.

Advertisement

Hide AdSome of these are encapsulations themselves, documenting much larger works, like the cards handed out by the 1,600 men in First World War uniforms who appeared silently in city centres around the UK to mark the centenary of the Battle of the Somme in his project We’re Here Because We’re Here. Others have appeared as billboard ads and bumper stickers. Some are posters for exhibitions or gigs.

Many are text works, by turns pithy, poetic and political, from the self-explanatory More poetry is needed to the philosophical Every age has its own fascism (Primo Levi), the succinct Strong and stable my arse, to the quirky Don’t not eat octopus. Rock lyrics are celebrated: one poster series frames quotes from Bowie and Cobain as if they were Bible verses (“Kurt ch.1 v.2”). And some are simply genius acts of observation, like the reproduced sign from the DJ booth in a long-gone nightclub reminding DJs to play calming music 45 minutes before closing time.

Music, politics and social history are recurring themes, as is Deller’s fascination with Stonehenge and “English Magic”. The major events of the last three decades are chronicled, from the invasion of Iraq to the Brexit vote. If anything, Deller’s political claws have got sharper in recent years, with good reason. “Welcome to the Sh*tshow” reads one sign emblazoned on a post-Brexit union jack. A new billboard is right up to the minute with “Cronyism is English for corruption”.

Deller is superb with details: the frontage of Modern Institute’s Aird’s Lane space is emblazoned with “Warning Graphic Content” posters in day-glo colours. Inside, the posters are patchworked on coloured walls, with giant post-it notes in Deller’s handwriting explaining bits of background.

While a po-faced chronological hang would be out of step with the spirit of the show, it would have been good to have more information on when the works were made as so many address specific moments. It’s a kind of social history filtered through the mind of one of our cleverest artists. However long you spend in it, there is always more to see.

If Deller’s work is generally designed to deliver its meaning straight away, sometimes with all the subtlety of a sucker punch, Cathy Wilkes, also currently showing at Modern Institute, is his polar opposite. Glasgow-based Wilkes, whose work was in the British Pavillion at the 2019 Venice Biennale, seems to grow ever more subtle, creating delicate warps in the fabric of reality and determinedly providing no clues to their meaning.

Advertisement

Hide AdPaintings and prints are arranged along one wall of Modern Institute’s Osborne Street Gallery, while a handful of sculptures seem to radiate out from them. It’s as if the human figures which have populated her tableaux in the past have become fragmented, ethereal, a pair of ghostly shoulders, an outstretched hand. Designed to be seen only in daylight, the whole show feels like it might fade before our eyes.

That said, there’s something hard-edged here. Look at the tiny drops of red (blood?) which star the floor from the wall to the first figure. In response to an unnamed menace, there is a kind of erasure, as if the occupants of the room were seeking to render themselves invisible. While Wilkes is adamant that any narrative here will be the one we supply, the hazy shimmer of this show has razor blades just below the surface.

Advertisement

Hide AdWith the legacy of COP26 still tangible in Glasgow, its themes are still echoing through the city’s galleries. Drink in the Beauty, a long-running show at GoMA inspired by recent acquisitions, is also the first show marking the gallery’s 25th anniversary. It celebrates art by women working with landscape and environmental themes (the title comes from writer Rachel Carson), and feels like a companion show to the excellent Dislocations at the Hunterian Art Gallery.

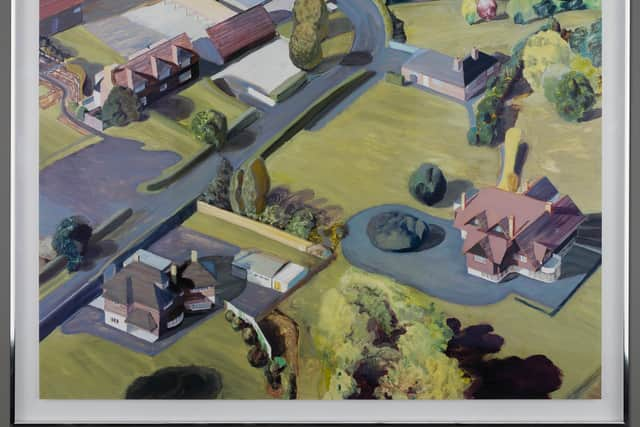

Carol Rhodes’ paintings and prints rarely feature people, but her underlying concern about the human impact on the world is increasingly clear. Ilana Halperin’s work is about geology and time; photographs of a fissure in Iceland at the meeting of the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates seem to convey as much about time as place. Kate V Robertson’s Better Versions are images from newspaper ads transferred onto archival paper by biro-rubbing, leaving hazy suggestions of idealised places.

There are cyanotypes by 19th-century botanist Anna Atkins, and rain-catchers made by Jacki Parry from hand-made papers. In a film by Jade Montserrat and Webb Ellis, Montserrat covers her body in North of England clay, gouging it out of the ground with her hands in a physical tussle with the landscape, an intense engagement by a non-white British woman with the land which might or might not be home.

At Tramway, Cambodian artist Khvay Samnang’s new film, Calling for Rain, has a direct environmental message. Commissioned by the Children’s Biennale National Gallery of Singapore, and suitable for all ages, it uses mythology, dance and impressive animal masks to create a narrative about climate change. The film is inspired by Reamker, the Cambodian version of Ramayana, and informed by time Samnang spent with the Chong people, an indigenous minority threatened by land grabs and deforestation and living at the sharp end of the climate crisis.

What we see, however, is a story. The monkey, Kiri, falls in love with the fish, Kongea, in a world in which habitats are threatened by the selfish behaviour of Aki the fire dragon, who grabs all the power and energy for himself. Though the film is wordless, Samnang doesn’t hold back on images of environmental destruction, trees being bulldozed and creatures dying as drought advances.

It saves its magic until the end, when the rain comes, both in the story and in Tramway, in one of those moments which synthesise real and imagined worlds and make the hairs stand up on the back of your neck. While one could argue that rain in Glasgow is not quite the godsend it can be in Cambodia, the point is powerfully made, and it serves as a reminder that there is a place for spectacle in an art world which has had to operate for too long via the small screen.

Advertisement

Hide AdJeremy Deller and Cathy Wilkes until 22 January; Drink in the Beauty until 23 January; Calling for Rain until 6 March.

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions