Art reviews: Islander: The Paintings of Donald Smith | Pandemic: A Personal Response to Covid-19

Islander: the Paintings of Donald Smith, City Art Centre, Edinburgh ****

Pandemic a Personal Response to Covid-19, Royal Scottish Academy ****

Advertisement

Hide AdRecently, I commended Edinburgh’s City Art Centre for coming out of all the difficulty of the pandemic guns blazing, with two first-class shows. Now, a week later, they have opened yet another, Islander: the Paintings of Donald Smith. Smith’s work is big and uncompromising, but it is not as well-known as it deserves to be and so this is a welcome introduction. His relative obscurity is partly because, like so many who began their careers in the bleak postwar years when there was no significant art market in Scotland, nor the opportunities to exhibit that brings, he had to make a living as a teacher. As a teacher, however, his approach and personality left an indelible impression. Arthur Watson, who went on to become President of the RSA, remembers his arrival in the classroom as a startling change from the spinster ladies who had taught him hitherto.

Smith was born on Lewis in 1926. His background was in fishing. After call-up and National Service which took him to India, he went to Gray’s School of Art. Ian Fleming, the school’s principal, said of him that he was “the outstanding student of his year… unquestionably a man of great ability as an artist.” Forceful personalities, dedicated Socialists and fine draughtsmen, the two men had much in common. Fleming championed drawing, but at Gray’s, Smith was also taught by Robert Sivell for whom drawing was the essence of art. After a number of years as a school teacher in Aberdeen, in 1974 Smith returned to Lewis. There he combined part-time teaching with painting and crofting. It was a challenging combination, but he carried it off and his ambition never flagged.

The City Art Centre show brings together a wide range of work, but does leave us without a clear idea of the course of his career. It may be pedantic to look for chronology, but with an artist whose work is unfamiliar, it is a help to be given an idea of how it evolved. It certainly doesn’t lessen the the work to be put in such a framework. Here the images in the catalogue, though numerous, are mostly untitled, apparently on purpose, while dates on the wall are sporadic. There is, however, a group of paintings dated to the 1960s that must reflect his early career. Eileanach (Island), for instance, is dated 1964 and Fisherman 1965. Both show the same blocks of heavy paint in blacks and earth colours. In the latter the fisherman’s red ochre canvas shirt becomes a leitmotif for the whole show. It was evidently his signature garment, too, for there is just such a shirt draped over a chair in front of the artist’s easel set up in the middle of the gallery.

These earlier works show a preoccupation with fishing and island life that stayed with him thereafter. Their heavy social realism was very much of the moment and appeared in John Bellany’s work at just the same time. A wild painting of cormorants is distinctly reminiscent of the younger painter’s work, too, but Smith was 15 years Bellany’s senior. There was no connection between the two, but they did respond to the same contemporary stimuli and also had a common background in Scottish fishing communities. Smith’s painting remained rooted thereafter in the real and earthy, not to say the salty, life of Lewis and its fishermen and women.

These early works however also show that as a painter he was ready to learn from the new abstract expressionism, mostly the kind coming out of Paris rather than the American sort. This new French painting was the subject of a major show in Edinburgh in 1958 and the bold work of artists like Nicholas de Stael or Sergei Poliakoff clearly made the same impression on Smith as it did on his contemporary, Joan Eardley. Smith’s Salmon Fisher, also of 1965, and the undated Lotaichean Crofts are in fact both reminiscent of Eardley’s work. The latter picture shows a row of slate-roofed Highland cottages with a flat grey sky above and, below, fields rendered as simple rectangular blocks of earthy colour. The whole thing is done with a palette knife used like a trowel in a way that clearly recalls de Stael. In Dearg agus Gorm, fishing nets are described with runs of paint like Jackson Pollock.

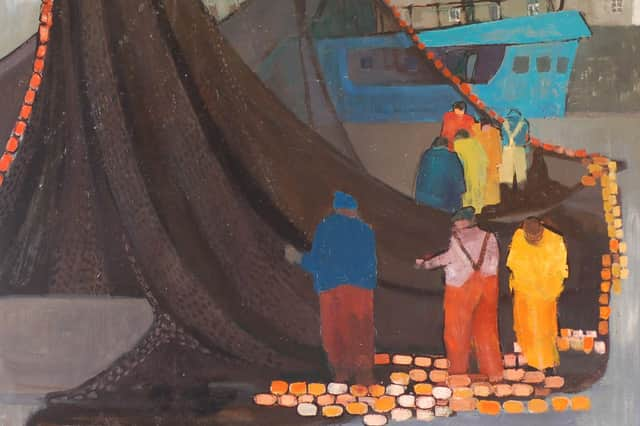

Like Eardley, however, Smith did not surrender to the siren song of abstraction. His commitment to his subject matter was too strong to be abandoned for what might have seemed self-indulgence. Instead, he sought to use the lessons of abstraction to make his own work more forceful. There are portraits here, both drawn and painted, including a self-portrait and a delicate painting of his wife and fellow artist Jewel Barrack. There are also landscapes and a lot of fine drawings, both in cases and in a slide show. The main impact of the exhibition, however, is made by a group of monumental paintings of fishermen and women working on the nets and the creels and other harbour tasks associated with boats and fishing. Wheelhouse, Fishermen with Creels, Dà Lasgair, Fishergirls and Mending the Nets all have real grandeur, but the bold simplicities of abstraction have much to do with their effectiveness.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe RSA’s imaginative response to the pandemic was to set up a special award. Twelve artists were each awarded £2,500 to create a work and the results are now brought together in Pandemic: A Personal Response to Covid-19. Some of the responses seem to be on the point, others way off. Ronald Binnie’s Zoonosis, is pretty blunt, a bat hanging in a butcher’s shop. Blair McLaughlin’s Venus shows a laptop on a rumpled bed, a girl’s face on the screen – enforced long distance lovemaking. Chris Leslie shows a film still of a deserted urban motorway, almost a symbol of lockdown, while Anthony Schrag’s Work Life Balance shows him taking indoor exercise and literally climbing up the wall. However, Steven Grainger’s Untitled I, a small, pierced vertical screen appears to be just another abstract sculpture quite untouched by the pandemic and its anxieties. Suzanne Antony’s Sprawl is also abstract, but its spiky, yellow, serpentine shape distinctly suggests a mood of unease.

Finally, Susie Leiper’s show at the Open Eye Gallery in Edinburgh was on the walls and about to open when lockdown happened. More than a year late, it has now finally opened. I reviewed it then so won’t do so again. It does, however, include new work and in all her work the physical presence really matters. Online won’t do.

Advertisement

Hide AdIslander: the Paintings of Donald Smith until 26 September; Pandemic: A Personal Response to Covid-19, until 20 June

A message from the Editor

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions