Art reviews: Hugh MacDiarmid, the Brownsbank Years | Tonico Lemos Auad | Alex Boyd

Hugh MacDiarmid: The Brownsbank Years, Biggar and Upper Clydesdale Museum ****

Tonico Lemos Auad: Unknown to the World, Cample Line, Thornhill ***

Advertisement

Hide AdAlex Boyd: Tir an Airm (Land of the Military), Stills, Edinburgh ****

In 1951, Hugh MacDiarmid and his wife Valda came to live at Brownsbank, a few miles east of Biggar. The cottage, where the couple were allowed to live rent-free by the farming family who owned it, had no running water or indoor toilet, but it became a haven from which MacDiarmid engaged with the wider world in the last decades of his life, and a place of pilgrimage for his admirers, from Seamus Heaney to Allan Ginsberg.

Hugh MacDiarmid: The Brownsbank Years grew out of the 2018 touring exhibition, Landmarks, created by Alan Riach, Professor of Scottish Literature at Glasgow University and also a poet, and artists Alexander Moffat and Ruth Nicol. Taking Moffat’s seminal painting Poets’ Pub as a starting point, the three explored the writers in the group through poetry, portraiture and landscape.

In lockdown, the collaborators revisited MacDiarmid and made new work. Moffat (who sketched the writer at Brownsbank in the last year of his life) has added to his existing suite of portraits with a new pub scene, Milne’s Bar, which includes Valda and film-maker Margaret Tait, portraits of MacDiarmid with Hamish Henderson (with whom he had a much-publicised “flyting” in the 1960s) and with Norman MacCaig.

Another shows MacDiarmid with composers Ronald Stevenson (a near neighbour) and Dimitri Shostakovich, a meeting which took place when Stevenson’s Passacaglia on DSCH was performed at the 1962 Edinburgh Festival. This painting – the colours in the background are the flames of Leningrad burning – is the ideological heart of show, reminding us that MacDiarmid, nationalist and internationalist, was also a statesman of sorts.

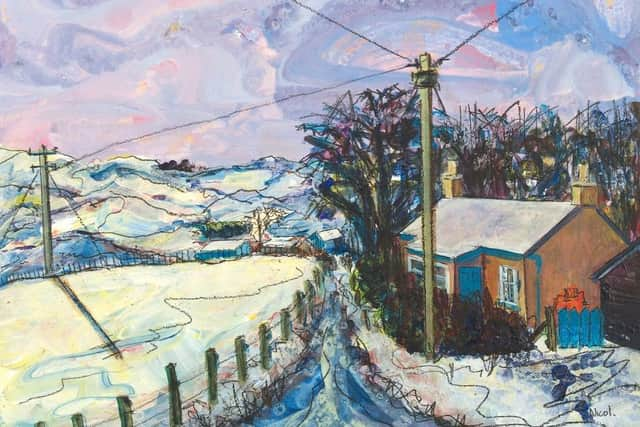

Nicol’s paintings of the cottage and surrounding landscapes through the seasons zing with colour, balancing a graphic energy of line and an expressiveness in tone and texture. Her interiors of Brownsbank (managed by the museum since Valda’s death in 1989) are vibrant and cosy, celebrating the details of everyday life: the armchairs, the wally dugs, the Fairy liquid by the sink. MacDiarmid and Valda each had one of the cottage’s two main rooms which they furnished in their own way; it was, as Riach writes, “a partnership / sustained by separation”.

Advertisement

Hide AdRiach (who also visited the couple) picks up on more detail in his poems: McDiarmid’s collection of paperback crime novels, his stockpiled copies of The Morning Star, the methodical way he did the dishes after every meal. He also sketches out his importance as a writer and public intellectual, at the centre the group of dissenters in the pub whose ideas have gone on to shape the country we now live in; who could “preside” at the meeting of the two composers “placid as an undisturbed volcano”.

Brownsbank now needs restoration and the MacDiarmid’s Brownsbank Trust aims to open it as a museum. With that development on the horizon, this exhibition is an invitation to consider MacDiarmid, often marginalised in his lifetime, and now in danger of being further relegated today, as a major player in Scotland’s intellectual landscape.

Advertisement

Hide AdNot so far from Brownsbank, at Cample Line, the contemporary art space curated by Tina Fiske near the Nithsdale village of Thornhill, Brazilian (now London-based) artist Tonico Lemos Auad is engaging with landscape and the past in a very different way. The centrepiece of his show is a series of found timbers, hefty beams and supports reclaimed from buildings being renovated or demolished. He uses the gallery’s exposed trusses to support one such beam which in turn carries another, attached by copper rods and appearing to float crosswise in the space.

While retaining the qualities of the found wood – cracks, weathering, notches cut for hinges or brackets – he adds his own embellishments: inlay, loops of copper, lengths of hand-woven rope. Auad is much concerned with craftsmanship, and here he lets it blend with the wood’s history until we are no longer always sure which is which. In the lower gallery, the cut lengths of wood stand on their ends, two big dark ones, like grazing buffalo, and a group of four in a corner, a family sheltering from the rain. Some are embellished with textiles, and there are also woven pieces on the walls which are treated to similarly subtle interventions, weaving and unweaving, embroidering and the opposite, where threads are removed to create images.

There is great attention to detail, and a sculptural playfulness with ideas of weight and weightlessness. Blocks of wood which might otherwise have been thrown away take on an aesthetic importance because of the attention paid them. But this work is about materials, not metaphor. One can admire it; any meaning beyond that is not readily revealed to the viewer.

Meanwhile, Alex Boyd, in the last of the Projects 20 showcases for emerging artists hosted by Stills in Edinburgh, heads out into the landscape with his camera to record how Scotland’s wilderness is being abused by the military. Walking and photographing at Cape Wrath, near Tain and near Kirkcudbright – all home to extensive training areas for forces from the UK and other NATO countries – he brings back images of red flags and warning signs, shell craters and bombed out vehicles.

His stark black and white photographs – and a film made in the Outer Hebrides – are most striking when there is a contrast at work: remote sandy beaches pockmarked with shells; wild moorland which suddenly reveals the wreckage of a tank. It’s shocking and it’s meant to be: “villages” are built from shipping containers to act as shell targets, the human shapes of “dummy insurgents” discarded on the moor.

The show is far from neutral. There’s a bitter irony in the fact that the more distant parts of our land are home to “wilderness, protected wildlife and depleted uranium rounds”. But if Boyd’s stance is not neutral, it serves to remind us that landscape is not neutral either. The Ministry of Defence is a major landowner in Scotland, and perhaps we should have an opinion about that. MacDiarmid certainly would have.

Advertisement

Hide AdHugh MacDiarmid: The Brownsbank Years runs until 28 November; Tonico Lemos Auad until 12 December; Alex Boyd until 13 November

A message from the Editor

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions