Art reviews: Howardena Pindell | Jyll Bradley

Howardena Pindell: A New Language, Fruirmarket Gallery, Edinburgh ****

Jyll Bradley: Pardes, Fruirmarket Gallery, Edinburgh ***

“I am an artist,” American artist Howardena Pindell has written. “I am not part of a so-called ‘minority’, ‘new’ or ‘emerging’ or ‘a new audience’.” These terms, she goes on to say, are demeaning to people of colour. What’s required is to “evolve a new language”.

Advertisement

Hide AdThus we have the title for Pindell’s first show in a public gallery in the UK, opening at the Fruitmarket in Edinburgh and touring to Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, and Bristol’s Spike Island. Pindell is now 78, having worked determinedly and consistently as an artist for nearly 60 years, and her words are timely at a moment when many artists of colour are being “rediscovered” or “reappraised”: extraneous labelling is not helpful. An artist is an artist, no more, no less.

Pindell’s long career can be read as a tussle with the question of race: to what extent she, as an artist of colour, chooses to engage with it; whether such engagement is inevitable, whether she intends to or not.

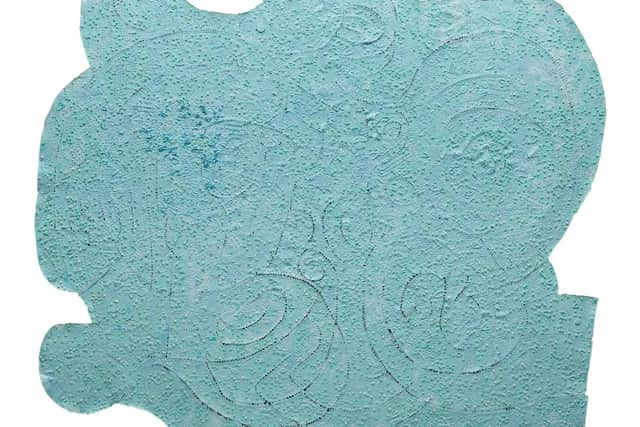

At first glance, her early works seem to sidestep it. The lower gallery at the Fruitmarket shows large, ambitious abstracts in dark, jewel-like colours made shortly after completing her MFA at Yale. Created by spraying paint through a hand-made stencil of dots, they have a texture which is blurred and velvety, a kind of pointillism. A few years later, she is making similar sized abstracts in creamy pastel shades, collaging paint with dots of paper from an office hole punch, adding sequins, thread, even talcum powder.

But, we learn, nothing here is apolitical. Engaging in abstraction in 1960s New York was already a political act, the territory having been staked out by white men. In doing so, she also caught the disapproval of the black community for not addressing race directly. Then the women’s collective of which she was a part rejected her ideas for overtly anti-racist work as being too “political".

Even her use of the circle has a backstory: visiting a root beer stand with her father in Kentucky in the 1950s, she was given a mug with a red dot on it signifying segregated utensils for black customers. It left her with a horror of circles, and her decision to use them was an act of reclamation. She would later say her pale abstracts were a response to the whiteness of the art world, the pressure to “whitewash” what she made.

After surviving a car crash in 1979, Pindell made a decision to make work with an unambiguous anti-racist message. Her film, Free, White and 21, made the following year, is both formally inventive and frankly autobiographical, prefiguring the work of various younger artists. In it, she recounts her own experience of everyday, endemic racism, then dons a blonde wig and stage make-up to play a young white counterpart who accuses her of being “paranoid” and “ungrateful”. It is still hard-hitting today.

Advertisement

Hide AdShe continued to make paintings in a collage style, using circles to new and devasting effect in Diallo (2000), which commemorates two young black men shot dead by police in New York: white circles to show the volleys of shots fired, red ones for the ones which found their targets. Separate But Equal Genocide: AIDS 1991-2, uses the form of the American flag and the names of young Aids victims to highlight the contrasting experiences of black and white people in the US healthcare system.

In 2000, she made Rope/Fire/Water, a film which catalogues racist violence in the USA from the end of slavery until the present day. Her narrative calmly recounts the dates and places of lynchings and burnings while a metronome ticks. Occasionally, the black screen gives way to graphic images, though perhaps these are not strictly necessary, the words are shocking enough. A Black Lives Matter coda adds the (increasing) numbers of black people killed by US police since 2015.

Advertisement

Hide AdRecent work has continued to mine the dark history of racist violence. Columbus (2020) is a large canvas using black-on-black text to catalogue racially motivated cruelty in the name of profit from Christopher Columbus onwards, particularly with regard to the severing of hands as punishment. A pile of sculpted hands, painted black, rests on the floor like a gruesome memorial. These works are violent in themselves, unflinching assaults on complacency. One might find them heavy-handed (no pun intended), but perhaps the subject matter leaves no room for subtlety.

However, we see another side to Pindell, too. In other recent work, she returns to working with collages of circles on unstretched canvases which are stitched together then painted, laborious works of lightness and colour which celebrate the Aboriginal songlines of Australia or the biological diversity of the oceans. They are a “relief” from the darker works, for her and for us, acts of healing, and of an artist of revelling in materials and colours and textures. An artist, nothing more, nothing less.

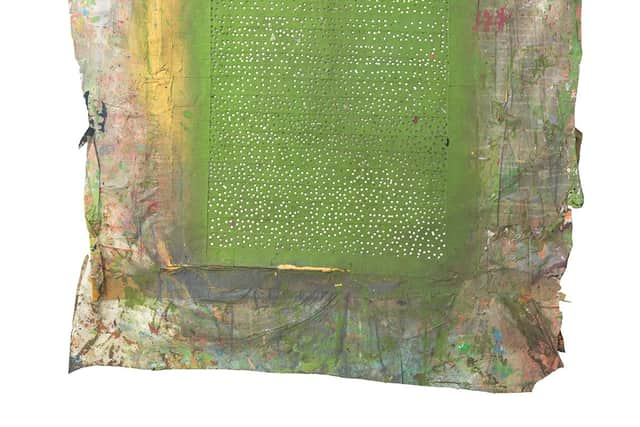

One’s head is full of Pindell as one moves on to the Fruitmarket’s new Warehouse space, currently hosting a site-specific installation by sculptor Jyll Bradley. Pardes is a grid of slanted perspex panels supported by diagonal wooden beams. Seen from one angle it seems to cut across the tall brick-lined space; from another it creates a new space which the gallery hopes will be used for events and performances.

The forms, we are told, are inspired by the artist’s research into the history of Scottish fruit growing: slanted greenhouses built in walled gardens or on sheltered slopes to maximise warmth and light. Bradley has used live-edge perspex which draws in the available light (not very much, in this space) and pushes it to the edges so each panel appears illuminated.

The ideas she is hoping to evoke are to do with growth, light and sustenance through winter, the coming together of man and nature in plant cultivation – the title comes from the word which gives us “paradise” – though the use of perspex seems to work against this somewhat, being hard-edged, man-made and not very sustainable.

This is the gamble of minimalism. Its success depends on the pieces falling into place and opening up a range of themes and resonances for the viewer. If it succeeds, it becomes a space to spend time and meditate on these ideas. If it doesn’t – and it didn’t for me, though this could be down to my failure as a viewer – it appears accomplished but sterile, less than the sum of its parts, a plastic garden where nothing grows.

Howardena Pindell until 2 May; Jyll Bradley until 18 April

A message from the Editor:

Advertisement

Hide AdThank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions