Art reviews: Flesh Arranges Itself Differently | Mohammad Barrangi | Leena Nammari & Louise Ritchie

Flesh Arranges Itself Differently, Hunterian Art Gallery, Glasgow ****

Mohammad Barrangi: Anything is Possible, Edinburgh Printmakers ***

Advertisement

Hide AdLeema Nammari & Louise Ritchie: Presence of Absence, Edinburgh Printmakers ****

When Glasgow University’s Hunterian Gallery and the Roberts Art Institute (formerly the David Roberts Art Foundation) decided to work together on an exhibition, there was no hesitation about the subject. Given the importance of medicine and anatomy in the Hunterian’s collection, it would be about the body, finding echoes and responses in modern and contemporary art.

However, what the two curators – Ned McConnell from RIA and Dominic Paterson from the Hunterian – have come up with between them is much more than a that-was-then-this-is-now set of comparisons. Flesh Arranges Itself Differently is a vibrant, often surprising, exploration of the subject. Delving into the riches of both collections, it brings together work by artists such as Michael Armitage, Rita Ackermann and Robert Rauschenberg, among many others.

It takes as a starting point the moment in which both science and art started to probe under the skin of the body, dissecting corpses to understand disease and drawing écorché plastercasts to learn how muscles worked. Interestingly, the more we understood about the mechanics of the body, the stronger the desire to depict the self in ways other than the purely figurative.

There is, of course, no neutral view of bodies. Here, the anatomical watercolours of Robert Macaulay Stevenson, made while studying art in the 1870s, hang opposite the striking paintings of contemporary Swiss artist Miriam Cahn, challenging the canonical depictions of women with works at once confrontational and ethereal.

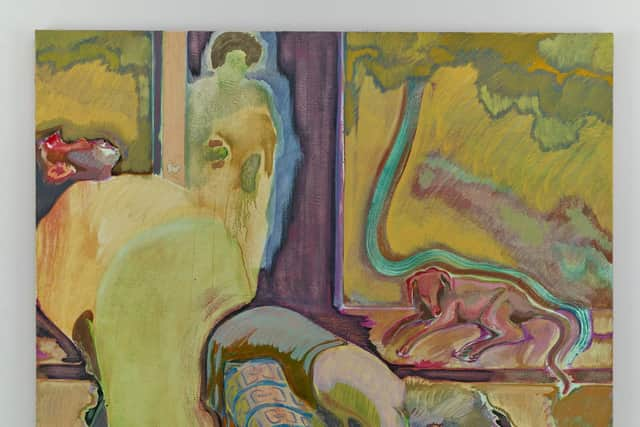

Michael Armitage, in a superb painting like Sun Wukong in Gachie, engages with the politics of Chinese industrialisation in his native Kenya by painting the Monkey King from Chinese mythology in the guise of a black African worker. Vietnamese-Danish artist Danh Vo writes on an Andy Warhol silkscreen of the electric chair the words “born out of a uterus I have nothing to do with”, his own defiant statement of cultural dislocation.

Advertisement

Hide AdArtists explore different ways of portraying the self: Ilana Halperin depicts the Eldfell volcano which erupted in the year of her birth and has become intertwined with her own story; Tamara Henderson’s fabric collage draped on an armature is both costume and sculpture; Huma Bhabha’s totemic sculpture, What is love, half styrofoam, half cork, is striking in its sense of presence. Rita Ackermann’s chalk drawing seems to shift in and out of figurative depiction, simulatenously drawn to it and drawn to erasing it.

It’s no coincidence that all these artists are women. Another particularly arresting work here is Christine Borland’s film Simwoman. Exploring the field of anatomical mannequins used for medical training, she discovered that only male and child models existed – there was no female. So she created one by casting her own face, breasts, hands and feet in wax and laying them on a male mannequin. The slowing panning camera does more than address a gender imbalance, it reveals a creature which – despite its mechanical breathing – is also intensely, poignantly human.

Advertisement

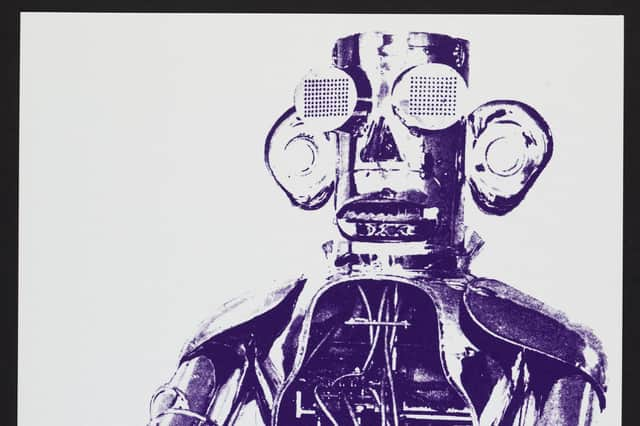

Hide AdPrints by Eduardo Paolozzi from the 1960s which explore aspects of the splicing of humans with robots act as a hinge into the second part of the show which explores more abstract depictions. Liliane Lijn’s Cosmic Flares III is cosmologial as much as corporeal, and as fresh today as when it was made in 1966. German outsider artist Horst Ademeit obsessively annotated polaroid photographs to depict what he believed were the hostile “cold ray” forces of a conspiracy. While the dot paintings of Yayoi Kusama seem to be both depictions of an internal state of mind and a way of controlling it, American painter Loie Hollowell plays with the space between figuration and abstraction with circles that suggest breasts and bums.

Many of these works were surprising, a few puzzling. The inclusion of four works by Ayan Farah feels like an unusual choice in a show about the body, given that her works are often made with processes removed from the artist’s hand. But one leaves impressed, once again, at how much has been fitted in to this awkwardly shaped gallery, and how works of such impressive calibre spark off one another to illuminate a subject in new ways.

Iran-born Mohammad Barrangi, currently showing in the main gallery at Edinburgh Printmakers, has some interest in the body too. His drawings of hands and arms (he has a disability in his left hand) echo some of Macaulay Stevensons’ paintings. But, for the most part, this show is more concerned with flights into the fantastical.

Barrangi trained in illustration in Iran, coming to the UK with refugee status and completing his studies at the Royal Drawing School. His work has recently been purchased by some major collections and his show at Edinburgh Printmakers launches In From The Margins, a Europe-wide project which offers support to artists from refugee and migrant backgrounds.

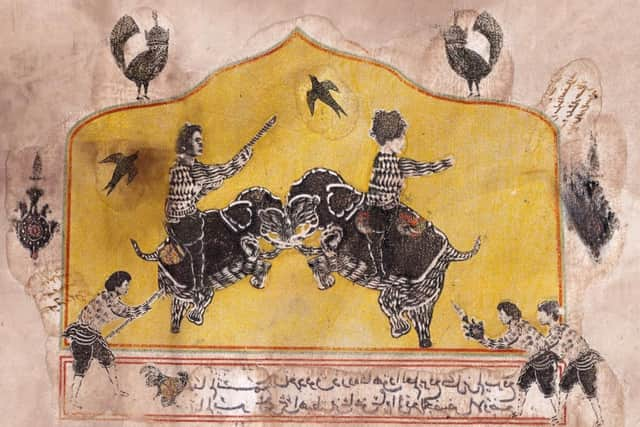

His figures – a courtier with a rabbit’s head, a sprite on a zebra’s back – call to mind 19th century illustrations, Tenniel’s work on Alice in Wonderland, for example, and he creates textures in his prints reminiscent of ancient manuscripts. But they splice together many techniques and inspirations: collage and calligraphy; Persian miniatures, scientific illustration and some of Edinburgh’s stranger statuary; mythology, game-playing and the occasional innuendo.

The presentation is theatrical – two unicorn-headed women point our attention to the large work on the back wall – and the whole thing sizzles with an accretive postmodern energy. But, while the audience are invited to enjoy all this, it’s difficult to get beneath the surface, to untangle what it might mean and how it might move us.

Advertisement

Hide AdNot so in the show upstairs, which brings together the work of friends and long-time collaborators Leena Nammari and Louise Ritchie. The two bodies of work face once another across the balcony space in a quiet conversation about the meaning of home, and the presence which lingers despite loss.

Nammari, who is Palestinian, is working with designs from Palestinian embroidery printed onto porcelain paper-clay. Her porcelain tablets, each of them fragile and unique, speak of human connections. Accompanied by a list of the villages and towns which were erased in 1948, their inhabitants killed or fleeing, the work becomes an intimate, handmade witness to a larger loss.

Advertisement

Hide AdOn the other side of the room, Ritchie begins with a saucer cast in bronze, the last of her grandmother’s wedding china, now memorialised. Then, taking the pattern from the china, she reproduces it in different ways, embossed on paper, etched on to glass, dusted with gold, and embossed into porcelain in a work which looks as fragile as lace. A poem by her mother is letterpress-printed on to porcelain, looking almost like a cuneiform tablet.

These works are about how objects come to stand in for something else, for human beings and communities and relationships now lost. It’s about how ordinary things become precious because of what they represent – the absence and presence of people we love.

Flesh Arranges Itself Differently until 3 April; Mohammad Barrangi: Anything is Possible and Presence of Absence until 27 March

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions