Art reviews: Elizabeth Price | Matthew Arthur Williams

Elizabeth Price: Slow Dans, GoMA, Glasgow ***

Matthew Arthur Williams: Soon Come, Dundee Contemporary Arts ****

The ground floor gallery at GoMA has always been a challenging space. Whatever you put in it has to contend both with its architecture and with its history. It was built, after all, for a Glasgow tobacco merchant with money made in the triangular slave trade. Blacked out to show Elizabeth Price’s films, it feels vast and cavernous, but it’s almost a pity the space isn’t putting up its usual battle: it would add an interesting further layer to the multi-layered conversation within the work.

Advertisement

Hide AdPrice’s three films are mounted on a complex rig down the centre of the space and run sequentially, taking about 25 minutes. It’s perhaps the artist’s most ambitious work to date, made possible by a range of partners including London-based Artangel and Glasgow Museums, which has purchased the second film for its collection. Arriving at GoMA two years later than originally planned because of the pandemic, it coincides with another Price show in Glasgow, Underfoot, at the Hunterian Art Gallery.

Price, who won the Turner Prize in 2012, is interested in social history and labour, class and patriarchy, and in technology, from the jacquard loom to the dot matrix printer to an imagined future in which data files are stored in people’s DNA. Her projects often begin with archives: in this case photographs of British coal mines, a collection of men’s ties, and a selection of images of women’s formalwear, all from the 1970s-1990s. These inform the work, but become the jumping off point for stories which draw together the past, the present and speculative futures.

The first film, Kohl, the simplest and most evocative, spins a yarn of ghostly “visitants” inhabiting the flooded tunnels of disused coal mines. The third and most mysterious, The Teachers, is about an outbreak of elective silence among a group of academics who seem instead to be communicating through the taps and clicks of digital culture.

At the centre, physically and schematically, is Felt Tip, in which the four female narrators (the same four across all three films) talk about neckties and workplace culture, critiquing – not without humour – hierarchies based on gender and class. These “administrators” are also the voices of the future, though it seems that in the future they are still exploited.

Very rarely does Price use what one might describe as conventional “film”. These are multi-channel digital constructions of found images, text, animation and sound (a loud, immersive, almost intrusive soundtrack by Price and Andrew Dickens). Words write themselves across the screen as if they were being typed as we watch, sometimes accompanied by keyboard clicks.

Motifs and references are densely layered. There might be the upside-down silhouette of a pithead, the close-up weave of a tie, the abstracted shape of an evening gown unfolding in mirror image or a slow-dancing high-heeled shoe. There is much wordplay and allusion, suggestion and connection: ties, fountain pens and phallic symbols; coal and eyeliner; evening dresses and academic gowns. A data-storage icon replaces the crest in the pattern on the old school tie.

Advertisement

Hide AdNo one will catch every allusion, and with such a dense weave of material it’s up to you what you take away. Are there references to the environment, to diminishing resources, the demise of patriarchy (or its persistence), the consequences of our over-digitised lives? Probably. They won’t be handed out on a plate, but it might be worth packing your metaphorical fishing rod.

Glasgow-based Matthew Arthur Williams, currently the subject of a solo show at Dundee Contemporary Arts, is interested in archives too. He draws on both official and personal histories. In fact, one of the central contentions of this show is that we are each a living archive of the things which have made us who we are, an archive still under construction.

Advertisement

Hide AdWilliams, one of a number of black artists whose work has come to prominence in Scotland, trained in Manchester in photography. Now he works across sound and film too, but the careful eye of the photographer is always present in this show which brings together still images and a newly commissioned 20-minute film, Soon Come.

The film is a thoughtful exploration of his own family’s heritage. His mother left Clarendon, Jamaica, in the 1960s as a child, following her parents who had found work in Stoke-on-Trent. Her father was a bus driver: his badge recognising five years of safe driving is a recurring image in the show. Williams collages film from newsreels and archives with the voices of his mother and others of her generation and adds film of the area today: derelict buildings, demolished factories, houses to let.

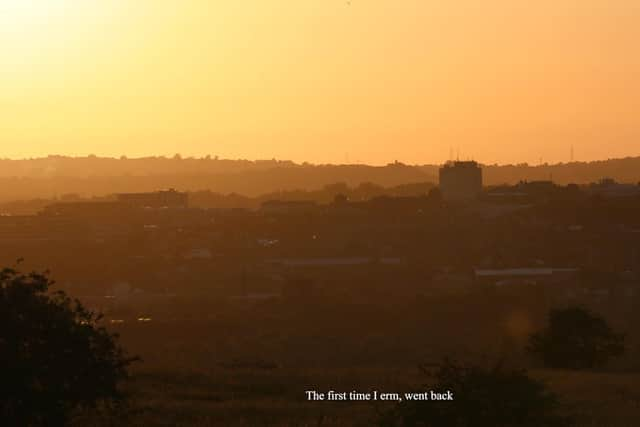

It’s a complex weave of juxtapositions: an authoritative broadcaster voice talks about immigrants losing their culture and customs; a black man talks about the prejudice he faced; a motorway cuts through field; a factory belches smoke in a green valley; a kestrel hovers; the sun sets. Many in that generation planned to work in the UK for five years then return home; few did. Yet they made a kind of home where they were, and their children grew up with a complex sense of what that word means.

The film is shown on two screens which face one another, putting us, the audience, in between two states which can’t quite be reconciled: Jamaica and England, past and present; public and private, personal and political. Nevertheless, the upbeat tones of reggae band The Chosen Few singing People Make the World Go Round seem to end with, if not a high note, then a sense of hard-won acceptance.

With the film is a collection of photographs, some echoing the film locations, others capturing places, faces, a church congregation in Jamaica, feet shuffling at a graveside. These prints were made in the darkroom with the time and care that implies, but the pages are allowed to curl and twist as they respond to heat and light, a fragile, living archive.

Standing out alongside them is a series of self portraits of Williams’ own body, in harsh, contrasting light. But perhaps the show itself is a kind of self portrait, about how one life, one self, is the product of all that has come before. It’s thoughtful work in which the personal does not exclude the viewer. One leaves wanting to ponder more deeply the building blocks which make up one’s own personal history.

Elizabeth Price until 14 May; Matthew Arthur Williams until 26 March