Art reviews: Elizabeth Price | Lara Favaretto | Nira Pereg | Qiu Zhijie

Elizabeth Price: Underfoot, Hunterian Art Gallery, Glasgow ***

Lara Favaretto, Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh ***

Nira Pereg, Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh ****

Qiu Zhijie, Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh ****

The grand frontage of Templeton’s carpet factory – inspired by the Doge’s Palace in Venice – still dominates the view across Glasgow Green. Templeton’s merged with Elderslie-based Stoddards in 1983, and the archives of both companies (Stoddards closed in 2009) belong to the University of Glasgow. Underfoot, by Turner Prize winner Elizabeth Price, is the result of a research fellowship looking at both archives.

Advertisement

Hide AdPrice, who works predominantly in digital film, was initially intrigued by the way in which the early “programming” of Jacquard looms prefigured the digital revolution. Down the rabbit hole of research, however, she became captivated by one of Glasgow’s most famous public carpets: the spectacularly psychedelic floors of the Mitchell Library’s modern extension.

Her major work, a digital film, Underfoot, is as much about libraries as about carpets. The Mitchell is the star, with photographs from the time of the extension’s opening celebrating its 1970s design (sadly, in black and white, so the impact of the carpets is much reduced). She also designed her own carpet, Sad Carrel, a tufted rug woven by Dovecot Studios’ Ben Hymers, displayed on a cocoon-like curve. It’s beautiful, making use of the circular motif found in the carpets in the Mitchell’s music department, meant to represent vinyl records and resonating with Price’s own visits to Glasgow for gigs with indy band Talulah Gosh.

Price’s work often touches on hierarchies of knowledge, social history and on stories which archives overlook, and in her film she is proposing a contrast between the highly structured nature of the library – its various departments which silo knowledge, the way design is used to control environmental factors such as noise – and its free-flowing, gloriously coloured carpet designs. While the film is meticulous, with superb use of sound and some great digital animation towards the end, as a critique of libraries it’s flawed, neither drawing out the faults of the current system or really making the case for a more freestyle approach.

In the end, the carpet archives are a point of departure, rather than the substance of the work, though two black and white photographs of women workers in the 1950s are among the most arresting images here. Those hoping for more of this, for work which sheds light on the archives, or probes the history of the factories and their predominantly female workforce, or even tells the story of the Mitchell carpets themselves, are at risk of being disappointed.

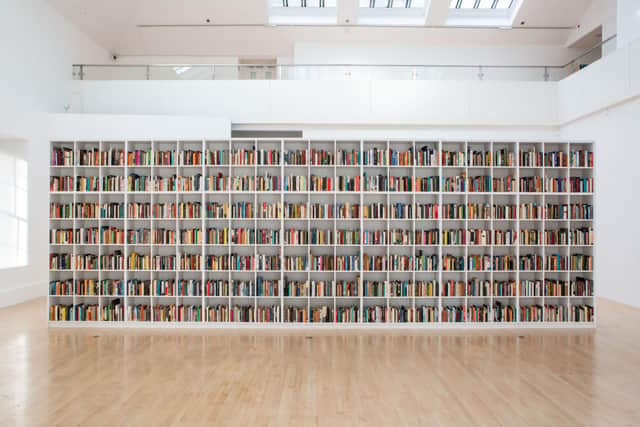

Lara Favaretto, one of three artists currently exhibiting at Edinburgh’s Talbot Rice Gallery, is interested in libraries too. Her work, Momentary Monument – The Library, is a collection of some 2,488 books which were destined to be pulped, locally sourced in Edinburgh for this iteration from surplus stock from libraries and book shops and from house clearances. Shelved in no order at all in a giant monolithic bookcase, each book contains a folded photocopy of an image from Favaretto’s own archive of thousands of found photographs, and each visitor is invited to take a book away.

For the bibliophile, it has all the excitement of a treasure hunt, not just discovering the books themselves – from FR Leavis to Marlowe’s Complete Plays, Archie Gemmell’s Autobiography to Rhododendrons for Amateurs – but finding the images concealed within. Many of the pictures feature structures, sculptures, or abstract shapes found in architecture. All are captionless; many leave you wanting to know more.

Advertisement

Hide AdAgain, there’s a point being made about structure, but whether it is bemoaning the lack or celebrating the anarchy, I couldn’t be sure. What seemed most striking, to me at least, is that so many books can be deemed surplus to requirements (what of the bereft rhododendron-grower?), and how a library – with its ethos of preservation and permanence – is in fact as “momentary” as everything else.

The three distinct shows are highly contrasting. Upstairs, Israeli artist Nira Pereg, presents films made in the Cave of the Patriarchs in the Old City of Hebron in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Believed to the place where Abraham is buried, it is among the most revered of religious sites for Jews, Muslims and Christians. Following a massacre in 1994 in which 29 Muslims were killed, it has been strictly divided into Jewish and Muslim areas, reinforced by bullet proof walls and checkpoints and the presence of the Israel Defence Force.

Advertisement

Hide AdPereg’s two-screen film, Abraham Abraham Sarah Sarah, focusses on the occasional days when, for special festivals, each faith gains access to the whole building for a 24-hour period. She films the moments of changeover: carpets being rolled up and stored, religious artefacts placed behind locked screens, Hebrew banners hung to cover up Arabic inscriptions. By homing in on the detail, the practical, the ordinary, she hints at the depths of division which surround this contested space.

Another peculiarity of the division of the Cave is that the minaret, used by the muezzin for the five-times-daily Muslim call to prayer, is in the Jewish part of the building. Pereg’s four-screen film, Ishmael, follows his walks to the minaret for each Adhan, under escort of heavily armed IDF soldiers. The four screens track his journeys back and forth through the building.

Filming this, she discovered another anomaly. When the Jewish settlers discovered the sunset Adhan coincided with their own Mincha prayer, they demanded their own call to prayer to replace it. This may be the only Jewish call to prayer anywhere in the world, and the only place in Israel or Palestine where one of the five Adhan is prohibited. Once again, by simply filming what happens, she conveys a sense of deep-rooted, complex hostility kept at bay by the rigorous observance of protocol. Proximity and repetition, one feels, does not breed greater tolerance, but only deeper resentment.

Finally, if taking the route suggested, one arrives at the Georgian Gallery and another contrast: the work of Chinese artist Qiu Zhijie, calligrapher and painter and vice president of China’s Central Academy of Fine Arts. This is a significant body of work, combining traditional Chinese techniques with contemporary practice, and deserves time and detailed looking.

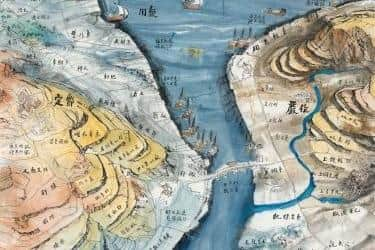

If you come in from Pereg’s show, you arrive on the balcony which displays his Colour Experiment series, hand-drawn maps inspired by contemporary digital imaging. They read like visual poems, marked with names, phrases and ideas instead of place names and topographical features: Ship of Fools, River of Forgetfulness, Peter Pan, Faust, Lolita, a medley of references by turns whimsical, historical and geopolitical.

Downstairs showcases several bodies of work, the long-format vertical pieces looking as if they were tailor-made for the recesses on the gallery’s walls, including Forms of Meditation, which depict abstract forms in traditional Chinese ink painting, and The Art of War, which draws on Chinese thinkers such as Sun Tzu (English translations of the writing on the maps are visible under ultra violet light, torches are provided). On the floor is a series of Paper Reliefs which mimic archaeological finds, from the historical (with titles like Greece and Babylon Tower) to the personal and domestic (Table Cloth, Lover).

Advertisement

Hide AdOverall, it’s a body of work borne of huge skill and expertise, bringing together the mastery of traditional techniques with a contemporary art sensibility and a playful imagination.

Elizabeth Price until 16 April 2023; Talbot Rice shows until 18 February