Art reviews: Douglas Gordon | Annalee Davis & Amanda Thomson

Douglas Gordon: k.364, DCA, Dundee ****

Annalee Davis and Amanda Thomson: Lightly, Tendrils, CCA, Glasgow ***

The times in which we live colour our appreciation of art. Particular works hammer this home, and the unveiling of Douglas Gordon’s k.364 at Dundee Contemporary Arts is one of them. Premiered at the Venice Film Festival in 2010, the film now has its first UK public gallery show, and lands in a very different world from the one in which it was made.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe events of World War II in Germany and Poland hang over k.364 like a melancholy shadow. Watching it now, while a 20th-century throwback of a war rages in nearby Ukraine, we wonder at the notion of history as progress. Perhaps time is cyclical after all.

The film begins with an impressionistic journey from Berlin to Warsaw which Gordon made in the company of two Israeli musicians, violist Avri Levitan and violinist Roi Shiloah, through the lands their families were forced to flee in 1939. It ends with a performance of Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat Major (catalogue number k.364) in Warsaw Philharmonic Concert Hall in which the two are soloists.

Two big screens sit at an angle to one another, and two mirrors pick up the images and stretch them into infinity. There are train tracks and overhead wires, trees whizzing past. There are scenes shot in a swimming pool in Poznan, a former synagogue commandeered by the Nazis.

There is – briefly – the kind of fragmented, occasionally profound, conversation which happens on long journeys. One of the musicians talks indistinctly about how his family fled. On a train in these lands, it seems, one can think of little else. “I don’t have a holocaust complex,” the other says. “But when I see these trees…” They talk about how one can feel connected to a past country, even when one has never lived there. And they talk about music.

While it is beautifully filmed, multi-layered and often poetic, there are two things about k.364 which make me uneasy. One is the casual, glancing way it touches on the holocaust. The other is that everything I’ve described so far happens in the first 15 minutes. The rest of the film is given over to the performance. Structurally, this makes it a game of two very unequal halves.

That said, the performance is a joy. The music sounds fantastic, and Gordon’s camera, close-up on the faces of Levitan and Shiloah, captures every nuance: the shifting emotions, the glances exchanged between them as they work. It feels like being in the front row at a concert and, for an audience largely deprived of concerts for two years, that feels rare and special.

Advertisement

Hide AdBut, whatever one might say k.364 is about – history, memory, friendship – it is above all about music, how it is both ephemeral and somehow eternal, how it exists only in the moment and can never be completely captured, even in this film. The charred pages of framed Mozart score in the next room explore this too: music can be destroyed, yet it is always with us, not just on paper or on a recording, but in our heads.

The uneasy question we’re left with is where the art in this project lies. Douglas Gordon has worked with geniuses before: Hitchcock in 24-hour Psycho, Zinedine Zidane, more recently Robert Burns. But by giving two-thirds of his film over to a performance of Mozart by world-class musicians, it seems he has met his match. Give Amadeus a chance and he’ll upstage you every time.

Advertisement

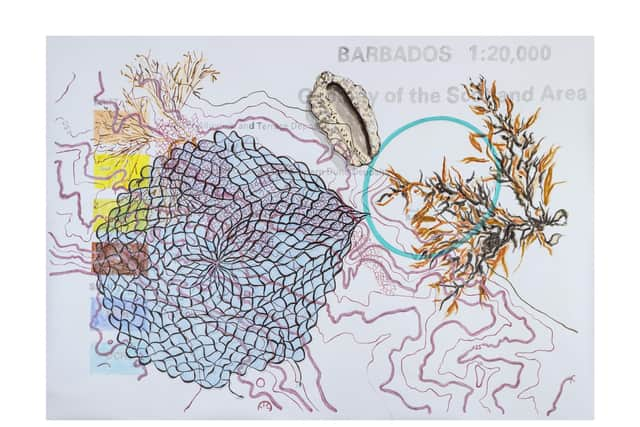

Hide AdMeanwhile, Barbadian artist Annalee Davis and Scottish artist Amanda Thomson also circle big themes in their two-person show at CCA. In practical terms, this is a frustrating show: there are no labels and the printed guide gives no information about whose works are whose. And while it’s true that both artists do make work about exploring their surroundings – Thomson in the pinewoods of Abernethy forest, Davis around the former sugar plantation on which she has a studio – this feels like two very different bodies of work awkwardly meshed together.

Imago, in the first room (but numerically the second – more confusion) is an immersive installation by Thomson about Highland moths. There are at least eight different screens, a text work and a layered soundtrack in which several overlapping voices talk about moth names (which are wonderful: “mottled beauty”, “dotted carpet”, “true lover’s knot”) and plant lore. There are so many components one quickly feels exhausted.

Her beautiful film, Twinflower, is also something of an information overload, telling us – surely – all there is to know about this rare and delicate plant with bell-shaped flowers the size of large raindrops. Her intimate knowledge of her subject and enthusiasm for it are not in doubt, but the impact could be greater if more rigorous editing was applied to the material.

Thomson has mapped her walks using GPS and used the maps to make photopolymer etchings and a digital print. Davis uses a wall to map the contours of the Scotland District on the East Coast of Barbados, decorating it with drawings of seeds and sea creatures, but the heart of her work is in the buried history of the inhabitants.

On the opposite wall, fragments of pottery unearthed on the land spell out the name “Frances” on pages of old plantation ledgers (Frances appears on the will of the one-time owner Thomas Applewhaite in 1816, described as his “little favourite Girl Slave”).

The third room (numerically the first) is more of deep-dive into Davis’ work. She has taken fragments of a lace tablecloth and sewn seeds into them, made a tea service from local Barbadian clay decorated with pottery shards. There are herbs drying, tea tastings on weekends, and What’s the Opposite of Erasure?, a copy of The Atlas of British Flora, in which the maps of plant species are overlaid with the names of 152 Scottish women sent to Barbados as indentured labour.

Advertisement

Hide AdIt’s all atmospherically presented, but the way the works are realised lacks nuance. In the atlas, for example, one name is painted per page in rose-coloured ink, but no more information is given, though something about these women is clearly known. Why are the seeds stitched to the lace? Why are we drinking tea? If the subject was less interesting, less important, we might not be troubled by these questions. Precisely because it is both of those things, we want to know more.

Douglas Gordon until 7 August; Annalee Davis and Amanda Thomson until 21 May