Art reviews: David Mach | Twenty Twenty One | gobscure | Sonia Mehra Chawla

David Mach: Heaven and Hell, RGI Kelly Gallery, Glasgow ****

Twenty Twenty One, Fine Art Society, Edinburgh ****

gobscure, Writing Liberté with Lips, Edinburgh Printmakers ***

Advertisement

Hide AdSonia Mehra Chawla, Entanglements of Time & Tide, Edinburgh Printmakers ***

Collage proved to be one of the most fertile inventions of early Modernism. People had cut things out and stuck them together since the invention of scissors and paper, but then Braque and Picasso started to stick cutouts onto paintings. The Surrealists, with a stroke of genius, saw that this opened the way to the completely free association of images. They could not have done this however without the huge surge in pictures cheaply reproduced in newspapers and magazines. Even so, as Max Ernst explored the surreal possibilities of collage, most of what he cut out and stuck together in wild conjunctions was still mostly black and white engravings. Then, as the century progressed, there were picture magazines, grainy newsprint photos and eventually cheap colour printing. It was an exponential expansion. Now we are almost drowning in images and that seems to be what David Mach shows us in Heaven and Hell, a show of his collages at the RGI Kelly Gallery – a world overwhelmed by images. These extraordinary artworks are surreal certainly, but his starting point seems not to be the Surrealists, but Hieronymous Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights. He has brought it up to date and even translated it to Glasgow.

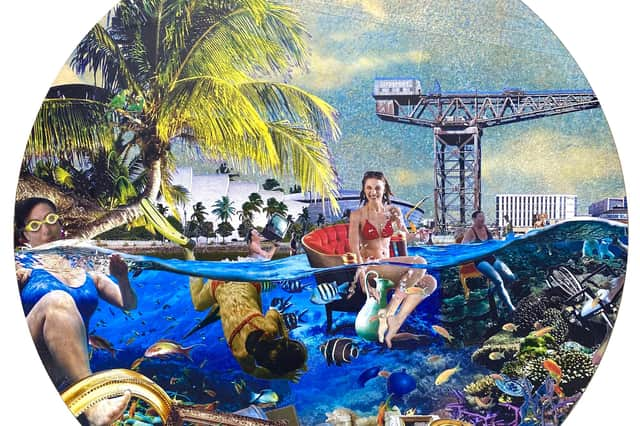

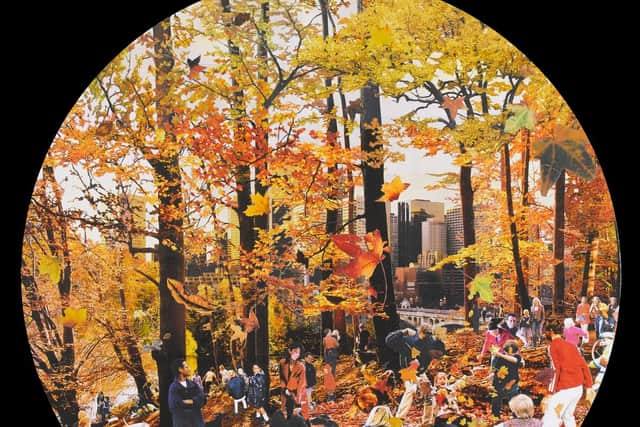

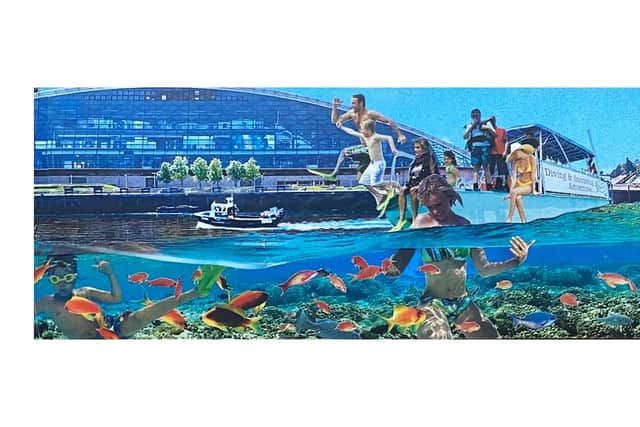

Bosch’s great triptych has heaven on one wing and Hell on the other. In between is a kind off purgatory where weird things happen. In addition, when the wings are folded, there is a circular painting of the sphere of the world on the outside. Most of are Mach’s collages are circular too and so he seems to have taken that hint from Bosch as his cue. It certainly adds to their weirdness. All the collages have the same teeming animation as Bosch, and mostly they consist of masses of figures with all sorts of things happening to them. Fittingly, too, they are either in heaven or in hell.

There’s Hell in Tokyo, in Paris and in Dublin. They are all very Hellish too. Hell in Dublin is a mass of figures, mostly swimming or tumbling into a swimming pool where the sea is rising and those in the water are battered by ice-floes. Crows circle above against a blood red sky. Hell in Paris is the most terrifying. Beneath the flaming sky of some horrific apocalypse, the Eiffel Tower is collapsing on horrific scenes of rape, murder, self-immolation and two terrified children. In Hell in Tokyo the figures are bigger but the apocalyptic mood is the same. A smartly dressed woman stands at a skyscraper window. She has lacerations on her back and the window is smeared with blood. A child is sleeping in a hideous mess while a man, gagged and blindfolded, stands nearby with mud up to his knees.

Heaven is a bit of a relief from all this horror, but as artists have always found, it is also less fun. Milton already had the problem in Paradise Lost, which prompted Blake to remark that Milton was of the Devil’s party without knowing it. Hogarth’s tragic Marriage à la Mode was a great success, but he never managed to complete its complement, the Happy Marriage. Mach’s Heaven in Athens is spring time is all flowers and green leaves and happy children blowing bubbles. His Heaven in Pittsburgh is autumn, but likewise all warmth and smiles.

The same mood prevails when he comes to Glasgow. In Buried Treasure, a tropical beach with happy holiday makers has been transported to Kelvingrove. The only note of discord is an abandoned car half-buried in the sand. In Glaswegian Eden, he has brought paradise to George Square with parrots, palm trees and happy naked people. Weegie Well is a bit of the same, but more grown up. A Clyde steamer sails past palm trees and bits of Glasgow, while in the foreground naked men and women happily splash around in the water, their bodies visible both above and beneath its surface.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe Scottish "old masters” in Twenty Twenty One at the Fine Art Society are altogether more chaste, though had he been included, JD Fergusson might have given David Mach a run for his money. From what we can gather, his partner Margaret Morris’s dance summer schools in the south of France were a bit like the Weegie Well. Mostly Scottish art is more decorous, though in David Robert’s painting of the interior of Rosslyn Chapel, it is not entirely clear what is going on. A girl and a child seem to be dancing and a barking dog is joining in, not really suitable behaviour for a church. Still it is a beautiful rendering of the interior of the chapel, faithfully recoding all the carved detail, but also the light. The view through a doorway to the level below is especially beautifully rendered. Also exquisite is a painting of Winton House in winter by Sam Bough. It sees to be morning, but the sunlight such as it is has not yet reached the hoar frost on the grass and cut wood in the shadow of the house high above.

One of the most striking pictures in this distinguished group which includes works by Raeburn, Ramsay, John Knox, DY Cameron and others, is a small gouache and watercolour by that most inventive of landscape painters, GP Chalmers. In its freedom and bold expression, it is comparable to a fine John Houston of sunset over cornfields, painted exactly a century later.

Advertisement

Hide AdYou couldn’t get a more striking contrast to these sober and accomplished artists from the past than the artist showing at Edinburgh Printmakers who goes under the name gobscure and whose show is titled Writing Liberté with Lips. This is art as polemic and the cause, their cause, is bisexuality. Some of the graphics are bold and vivid. An artist’s book, Anarkissed, edges towards concrete poetry though it could hardly be further in sentiment from Ian Hamilton Finlay, pioneer of the form, it is not so far in content. “Curlews, curfews, alibis, lullabies, goodbyes” is a sequence that has a bit of a Finlay ring to it.

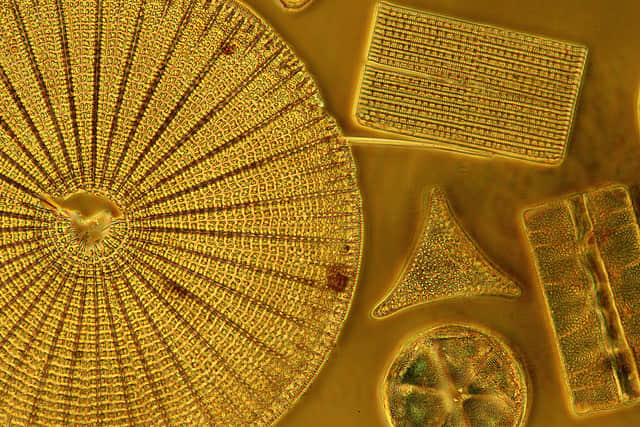

Also at Printmakers, in Entanglements of Time & Tide, Sonia Mehra Chawla has produced a poetic soliloquy on the North Sea and its margins. This consists of rather beautiful photographs of buildings, piers and other apparently solid human constructions being gradually reclaimed by the sea. Others are “living landscapes” – close up details of the sea’s margins – and, as this a print workshop, there are also delicate laser etchings of microorganisms. Altogether it is quite an intriguing documentary exercise.

David Mach until 16 October; Twenty Twenty One until 15 November; gobscure until 26 September; Sonia Mehra Chawla until 12 November

A message from the Editor

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions