Art reviews: David Austen & Hisham Matar | Joel Tomlin | John Knox | From Copper, Wood and Stone | David Forster

David Austen and Hisham Matar: The Boys – an Adventure, Ingleby Gallery, Edinburgh ***

Joel Tomlin: Sculptures, Ingleby Gallery, Edinburgh ****

John Knox: The Light Sublime, Fine Art Society, Edinburgh ****

Advertisement

Hide AdFrom Copper, Wood and Stone: Two Centuries of British Printmaking, Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh ****

David Forster: Play, Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh ****

David Austen makes films, prints, paintings and sculpture, but a rather whimsical process of free association seems to be a constant across these different media. He also works in collaboration with others. His film, The story of my death as told to me by another, is, for instance, a joint production with the novelist Rupert Thomson. In the film Austen, made-up like a clown, floats in empty space while the writer reads a script describing a dream he had of the artist’s death. At the Ingleby Gallery, Austen’s show, The Boys: An Adventure, is a similar two-hander combining voice and image, but instead of film, it matches a series of small abstract paintings with the voice of actor Khalid Abdalla reading a short story by Hisham Matar.

In the gallery the pictures, small, abstract, painted in gouache and all the same size, are hung in a single line along all four walls, so close together they are almost touching. The words come out of four speakers hung above head-height. You are recommended to sit on one of four benches each placed directly beneath a speaker to hear the reading. All very well, except that if you wanted to hear it all you would be there for quite some time. The written story goes on for 72 pages and takes three and a half hours to read. Words and images will be published later as an artist’s book, which perhaps makes more sense.

The story is told through the eyes of the younger of two brothers, aged nine and 12. They are not named, nor is anybody else except for “Mum” and “Dad”. Over an evening and apparently the following couple of days and nights, the young boy’s perspective on what is going on is quite nicely captured. Wherever it is that they are, life is evidently insecure. They don’t go home at night because it is not safe. They do not seem to need to tell their parents they are staying with strangers, but the next day they are with their father and mother. They then have various encounters and the story culminates as, speaking in whispers, the boys hide with their father and other men behind the pulled-down shutters of a cafe, while outside they hear ominous sounds of violence and the smell of tear gas percolates the shutters.

There is none of this in the 60 or so paintings on the wall, all elegant and delicately executed. With a bit of Matisse here, a touch of Agnes Martin there, echoes of Victor Vasarely, Elsworth Kelly, Paul Klee, William Scott and of many others too, the pictures offer a nice thesaurus of abstract imagery. By definition this has no reference beyond itself, however, and indeed we are told no connection between words and images was intended. That being so, it is all a bit self-indulgent.

The collaboration of artist and author began as a WhatsApp exchange of words and images at the beginning of lockdown in March 2020. The casual intimacy of such an exchange was no doubt intriguing to the two participants, but as a collaboration it hasn’t managed the transition from private to public that would be essential for it to work as art. All the same, the paintings are lovely.

Advertisement

Hide AdUpstairs there are a few more small gouaches by Austen, unrelated to the main exhibition, but in the upper room there is also a collection off small wooden sculptures by Joel Tomlin. Mostly they represent conventional still-life objects, jugs, bottles, musical instruments and the like, but also occasionally figures. In one or two cases, the objects are assembled into traditional still-lifes of objects on tables. All are carved in wood with an evidently deliberate lack of elegance and with a rough, but carefully patinated finish. The effect is quirky and delightful.

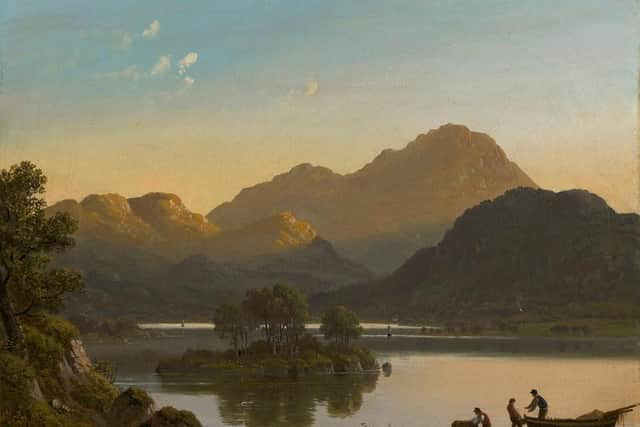

A show of Scottish landscapes at the Fine Art Society takes us back to an earlier time. It is built around a lovely group of six small landscapes by John Knox. Knox, who flourished in the first half of the 19th century, was really the first major artist to be based exclusively in the west, which naturally also provided his most familiar subject matter. Here there are two beautiful views of Loch Lomond, for instance, also the subject of one of his most familiar works, the two-part panorama of the loch in the National Gallery. Knox’s wife came from Keswick. For this reason, perhaps, the Lake District also featured in his work and the most beautiful picture in this group is a view of Ullswater as dawn lights the mountains, but has not yet touched the water below which, cool and still, remains in shadow.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe gallery has built a show of Scottish landscapes round this group of paintings by Knox. Either directly or indirectly, Alexander Nasmyth was Knox’s mentor and a small painting by him of travellers on a road with woods and a loch beyond certainly suggests the connection. Alongside these pictures are works by William McTaggart, Horatio McCulloch and Rev John Thomson of Duddingston. Others are less familiar, however. James Cassie, for instance, matches Knox’s painting of dawn with a beautiful sunset view from Kames Bay on Cumbrae looking across to the mountains of Arran. Equally outstanding and also by a less familiar artist is a painting of the Kelvin by John Milne Donald. It is a tranquil scene of ducks and barges, captured with a real sense poetry. These painted landscapes are backed up by etchings by John Clerk of Eldin, Muirhead Bone, James McIntosh Patrick and others.

Across the road at the Open Eye Gallery, From Copper, Wood and Stone: Two Centuries of British Printmaking is a more comprehensive selection of similar artists’ prints. There are around 70 in the show, and many are by familiar names like DY Cameron, Gerald Brockhurst and here too again both Muirhead Bone and McIntosh Patrick. An etching of Glencoe by the latter is very striking. A superb early etching by Graham Sutherland before he went a bit surrealist is also especially notable. A beautiful bookplate of a woman with a snake by Eric Gill, an artist who has more or less been cancelled, is a reminder of the problem of bad man/good art. There are also prints by artists who may be less familiar like William Walcot, Anthony Gross, Mabel Royds and Alfred Anderson, but who are clearly worthy of our attention. Eduardo Paolozzi, Alan Davie and Adrian Wiszniewski are among more recent artists represented in this intriguing and wide ranging show.

The Open Eye is also showing work by master watercolourist David Forster. The mood of his strange, carefully off-key paintings is summarised in the title of one of them, Secretly as witches creep (Auvergne). It is a picture of a church among trees. Beautifully painted, the light is carefully observed, but the colour key is subtly shifted from the natural towards the uncanny. Something similar happens in the painting Only the recent moon stared steadily back at her (Poland). The eponymous moon is visible through tattered clouds in heightened colours, while a tall ladder leads up to a platform in a tree. It may be a hunters’ lookout, but it appears vaguely sinister in the strange light the artist has contrived. By the use of similar lighting in Little brother took his little sister by the hand, a simple playground among trees suggests witches and the Babes in the Wood.

David Austen and Hisham Matar until 10 June; Joel Tomlin until 20 May; John Knox until 10 May; From Copper, Wood and Stone and David Forster until 27 May