Art reviews: Brent Millar | Norman Gilbert | Michael Craik | William Johnstone

Brent Millar: After the Rain, Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh ****

Norman Gilbert, Tatha Gallery, Newport-on-Tay ****

Michael Craik: Echo, & Gallery, Edinburgh ****

William Johnstone: The Inner Eye, Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh *****

Advertisement

Hide AdIf the earliest known paintings date from 40 or 50 thousand years ago, it is worth reflecting that those are only the ones that survive and that they do so only because they are painted on the walls of caves deep in the earth. There is no reason to suppose that our ancestors had not been painting on more fugitive surfaces for a very long time before that. It is clear anyway that painting with brush, medium and pigment and the peculiarly rich interactions of heart and hand and eye, of fluid paint and solid surface, of image and idea that they provide, is deep seated in the human psyche. It is a fact worth remembering when the simple act of painting is regarded in some circles as passé. That is hubris. It suggests we are superior to our ancestors. We are not. Our technology may be better than flint axes - it will also probably be our nemesis - but we ourselves are just the same.

These prehistoric reflections are prompted by Brent Millar’s lovely paintings at the Open Eye. He has shown from time to time in the gallery, but this is more comprehensive than any previous exhibition of his work that I have seen there. One room of the gallery is filled with paintings, the other with drawings and it all starts right at the beginning. The earliest work is an illustrated letter to Granny from Brent aged just four. There are one or two other childish works too. The show doesn’t then go on to fill in every artistic detail since that promising beginning, but it does include some fine drawings from his early years as an adult artist. There is for instance an eloquent large pencil drawing of his brother Kenneth from 1966. There are a number other drawn portraits, including three comical self-portraits of the artist shaving. There are one or two prints and several landscapes. A pencil sketch of a house in Newhaven dated 1968 is particularly satisfactory, just a few lines and pencil marks in different weights and it’s all there. No more need be said. This already shows the inimitable delicacy of touch that also gives such life to his paintings.

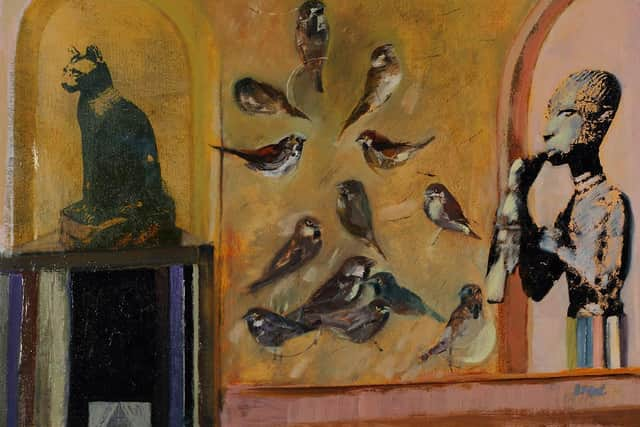

Birds are one of his favourite subjects and there is a happy symbiosis between their light movements and colourful delicacy and the way he paints. There are swans, canaries, hoopoes, bee-eaters, bullfinches and flocks of sparrows. An oil portrait of yellow canary against a plain black ground, another of a black swan and a third of two affectionate scarlet canaries are all particularly striking, while five owls of different species congregated on a branch are delightfully comical. A lovely painting of swans beneath the moon in Inverleith Park opens this bird motif out to the landscape though of course it is in the dark. But then he branches off to paint a herd of elephants in loosely handled gouache. A new departure here, too, is a group of ceramics, jugs, mugs and bowls. There are, for instance, five canaries painted on a white vase and five swans swimming round the inside of a lilac coloured bowl. The translucent glazes are perfectly suited to the artist’s way of painting and the birds all look wonderfully at home in their new ceramic environment.

Celebrated in a retrospective at the Tatha Gallery in Newport-on-Tay, Norman Gilbert is a very different artist. His tightly organised, patterned surfaces are the polar opposite to Millar’s loosely painted birds in drifting spaces. Where Millar is spontaneous, too, Gilbert took months for each picture. But both succeed, each in his own terms. Born in 1926, Glibert lived and worked into his nineties. The earliest work here is from 1959 and the latest from 2019. It’s a 70 year span. Throughout that time he is consistent in his concern, on one hand with the intimate and domestic, and on the other with pattern. Already in Paul from 1963, for instance, a picture of a boy sitting by a table, the table is flat yellow, the floor flat blue and the composition is tipped towards us to emphasise its patterned flatness. In a documentary nearly 50 years ago he said of his work that he was trying to produce “a sort of picture where everything fits together.” Its like a jigsaw composed of patterns and carefully balanced colour. The people, often members of his family, fit into this intricate web too. There is no background and foreground division so they seem suspended in a mosaic of colour. To get the colour balance right, too, they sometimes end up with blue faces and pink hair.

In the seventies, in pictures like Patterns in Blue and Red from 1977, for instance, a boy and a girl standing in a room with a fireplace, furniture and patterned wallpaper behind them, the flat colour and sharp edges clearly recall Matisse’s cutouts. There is even a rubber plant whose leaves are a classic Matisse motif. There is none of Matisse’s spontaneity however. Everything seems fixed in its place, but it is not always completely passive nevertheless. He echoes Balthus as well as Matisse and there are often erotic undertones. Girls sit in Balthus poses looking impassive, but with their skirts rucked up. In Mark and Barbara in the Attic, Barbara, a provocative hand between her thighs, looks challengingly at a rather nervous Mark. A nymph in the wallpaper behind her echoes her gesture as a satyr charms her with his flute. Not all these pictures are so loaded however. Latterly he focussed on still-life with frequent memories of Matisse, but with overall patterning like Vuillard.

The pure simplicity of Michael Craik’s abstract paintings at the & Gallery make another contrast to Gilbert’s complexities. Craik paints in layers of colour, but rubbed so that the colour, beneath, usually dark, is visible through the dominant top layer. Thus, for instance, he lays clouded blue over red and so, even though the surface is polished smooth, there is a hint of depth and distance. There are echoes of Joseph Albers and Mark Rothko in his images.

Advertisement

Hide AdRothko is brought to mind at the Scottish Gallery too. There, 15 of William Johnstone’s abstract brush drawings have been hung together. The effect is dramatic and very moving. Dating from the seventies, Johnstone made bold and simple gestures with a broad brush laden with dense black ink. It is like calligraphy, but it has its own fierce energy. Rothko again - seeing them all together like this reminded me of impact of his chapel in Texas. But these drawings have their own authority. Johnstone was beholden to no-one. A lifetime’s experience is distilled into the simple gesture of his hand. He is present here in person too. One drawing, just as abstract as the others, but a bit more complex, is titled Anonymous Portrait. I recognised the artist himself immediately in its web of abstract lines. That is some alchemy.

Brent Millar, Norman Gilbert and William Johnstone until 24 October, Michael Craik until 4 November

A message from the Editor

Advertisement

Hide AdThank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

The dramatic events of 2020 are having a major impact on many of our advertisers - and consequently the revenue we receive. We are now more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription to support our journalism.

To subscribe to scotsman.com and enjoy unlimited access to Scottish news and information online and on our app, visit https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions

Joy Yates, Editorial Director