Art reviews: Bernat Klein | Hannah Lim | Catherine Baker | Ade Adesina | Outside Edge

Bernat Klein: Design in Colour, National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh ****

Hannah Lim: Ornamental Mythologies, Edinburgh Printmakers ***

Catherine Baker: Held Edinburgh Printmakers ***

Advertisement

Hide AdAde Adesina: Parallel, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh ****

Outside Edge, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh ****

Bernat Klein brought a bit of the Bauhaus to the Borders and from his base near Galashiels became an internationally recognised designer. He left his mark on the era, particularly in women’s fashion in the 1960s, but subsequently also through other branches of design. In it all, colour was key. “Clothes and colour are at least as important as food and drink,” he wrote, “but perhaps nearer, in their source and in the senses they satisfy, to music, poetry and painting.” He was himself a painter as well as designer and the colours of the Borders were a key part of his inspiration.

Klein was born in 1922 into an orthodox Jewish family in what was then Yugoslavia and is now Serbia. A new exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland marks his centenary. The show is drawn from the extensive archive the museum holds, but it also includes fabric samples and costumes from other collections. Brushed mohair was his invention and signature fabric and among the items on view is the brushed mohair Chanel suit from 1963 that was his breakthrough into haute couture. In 1965 he opened his own showroom in Paris. A press cutting notes that no less than 18 of his fabrics were to be seen in the couture collections that year.

In 1940, no doubt to get him out of Europe, Klein had left Yugoslavia to study at the Bezalal School of Arts and Crafts in Jerusalem. There he was taught by Mordecai Ardon. From 1920-1925, Ardon had been taught by the likes of Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky at the Bauhaus. He in turn passed on to his own students their radical ideas about design.

After the Bauhaus, Ardon was also taught by Max Doerner, a painter and colour theorist, so when Klein went to study textile technology in Leeds in 1945, he already had some very new ideas in his metaphorical school bag. Textile business brought him to Scotland and in 1952 he and his new wife Margaret Soper set up a textile business, Colourcraft, in Galashiels.

Klein painted abstract pictures in bold slabs of colour and might have enjoyed a minor place in the story of post-war abstraction. His interest seems primarily to have been in colour harmonies and his painting informed his textile design. A master of colour, he built up what he called his "five thousand piece” dictionary of colour charts. Paintings and textiles put side by side here demonstrate a close relationship. Indeed one of his remarkable innovations, random or space dyeing combining different colours in a single yarn, could be seen as translating painting directly into wool. As they blend, the constituent colours generate further colours creating the marvellous, rainbow effect in his fabrics. He also invented a velvet tweed with a texture even closer to his paintings. In applying his ideas, not just to what was fashionable, but to what suited the individual woman, Klein also developed a personal colour guide based on eye colour with a view in turn, no doubt, to the customer finding suitable colour matches in his fabrics.

Advertisement

Hide AdFashion changed, however, and Klein moved on. He branched out into printed fabrics and interior design. High Sunderland, his modernist house, flat-roofed, square and with glass all round, designed by Peter Womersley, was pioneering in this field and he went on to operate a very successful design consultancy. His wife Margaret also marketed dress and knitting patterns. The company they ran together had extraordinary reach from international high fashion to the homely and domestic. It was all very much in the spirit of the Bauhaus.

Ornamental Mythologies at Edinburgh Printmakers by Hannah Lim is a show of prints, small coloured objects and larger sculptures of painted laser-cut wood. In her accompanying text the artist discusses the exploration of colour in her work and cites as an inspiration an idea she attributes to David Batchelor: fear of colour as feminine permeates Western culture. It is an idea that is pretty hard to reconcile with Klein’s work, or indeed with the great tradition of western painting from which it derives. Lim’s iconography includes dragons and lions and, as the title hints, the whole ensemble has a vague flavour of chinoiserie. It reflects, she says, her exploration of her own mixed heritage coming from Singapore. It is all coloured, but not very boldly. She could maybe take a lesson from Klein.

Advertisement

Hide AdHeld in the upper gallery at Printmakers is a show of mostly photographic prints by Catherine Baker. She works in a crossover between art and health, not art-therapy, as you might suppose, but, it seems, rather art as observation. The most interesting part of her show is a text exploring an analogy between tree growth and curvature of the spine in adolescents, the medical field in which she evidently has expertise.

Her prints, mainly of trees and hands with occasional pieces of wood incorporated into the ensemble, don’t really make much sense, however, except as illustrations to this text. What she does is clearly admirable, but in this context surely the images should have priority and the text only illuminate them, not vice versa?

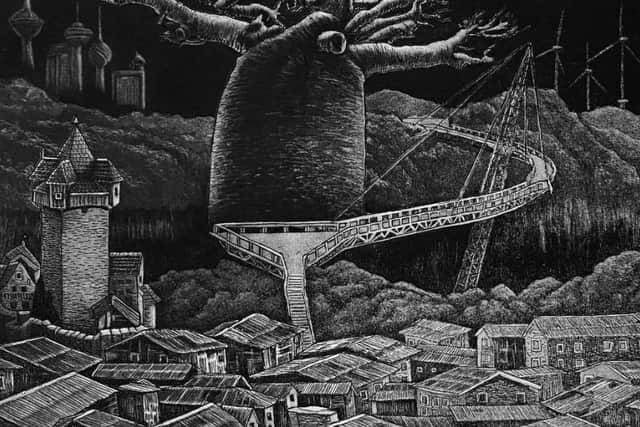

There is nothing so elusive about Ade Adesina’s linocuts at the RSA. He has made something quite new out of this homely medium, creating intricate and complex images often on an enormous scale. There are elements of his African heritage in his iconography, notably his favourite baobab tree, and there is commentary too on ecology and the serious state of the natural world, but it is really just the sheer strength of his images that is so telling.

Also at the RSA, Outside Edge is an international collaboration of four artists, Hongshen Ju and Professor Xu Yun from China and Kate Downie and Helen Goodwin from the UK. Their collaboration grew initially from time Helen Goodwin spent in China. However, Kate Downie who has always worked extensively in ink on paper has also taken a course on ink painting in Beijing. The four-way collaboration began with a shared residency at Carsaig Bay on Mull in 2019. The pandemic prevented the planned reciprocal residency in China taking place and so the collaboration went online.

All four artists have an interest in landscape, not as a passive thing, but as reflecting our living and changing environment. Their works have real affinity and the results of their interaction are impressive. Downie’s luminous watercolours of sky and water find an echo in the beautiful brush drawings of the two Chinese artists, particularly when she paints on linen. Their work in turn seems to be profoundly in sympathy with Goodwin’s brooding photographs of rocks and sea, or indeed with a brilliantly apposite photo of Chinese ink dissolving in the water of the Atlantic Ocean, or simply photographed as it spreads on a sheet of Xuan paper, an ancient Chinese paper much favoured by calligraphers and brush painters.

Bernat Klein until 23 April 2023; Hannah Lim and Catherine Baker until 20 November; Ade Adesina and Outside Edge until 13 November