Art reviews: Barbara Hepworth | Steven Campbell

Barbara Hepworth: Art and Life, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh *****

Steven Campbell, Dressing Above your Station, Tramway virtual exhibition ****

Advertisement

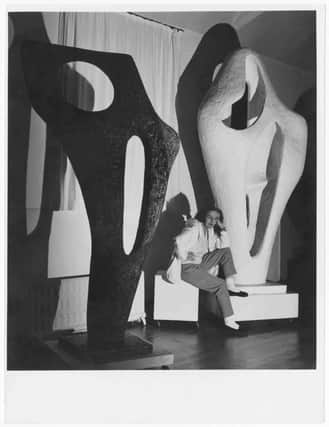

Hide AdBarbara Hepworth was born in Wakefield, Yorkshire, in 1903. In later life she recalled driving with her father through the countryside as a child at “the furious pace of about 25 miles an hour” and connected flying through the Yorkshire landscape in this way with her sculpture; “the hills were sculptures; the roads defined the forms.” Certainly a conversation between line and form does characterise much of her work. She was of course principally a sculptor, but in drawing line defines form and amongst much else in the comprehensive show of her work occupying the whole Gallery Two of the SNGMA, the generous display of drawings and also of prints are both striking in themselves and offer a significant enlargement of our understanding of her work.

At school in Wakefield she was encouraged by her art teacher, Miss Murfet, and a rather beautiful drawing of her, by the 17-year old Hepworth confirms her judgement of her pupil’s promise. In 1921 Hepworth went to the Royal College and four years later married the sculptor John Skeaping. Superb figure drawings from the late 1920s are echoed directly in a series of semi-figurative sculptures in wood which are amongst the most beautiful things in the show.

The earliest of them, Torso from 1929, is recognisably a female torso in the truncated form familiar from classical sculpture, but simplified and refined. Here and elsewhere she often selected a beautiful, exotic, but conspicuously hard wood. This figure is picardo wood. In another taller, slimmer Torso from a couple years later she used African black wood, but the resulting finish is always very beautiful, not least because her care and effort are still an almost tangible aspect of the sculpture.

This is also true of Figure in Sycamore, a figure standing on a massive piece of tree trunk, head turned. The bold simplification of this figure invites comparison, though not to her disadvantage, with Henry Moore. Both artists were no doubt responding to Picasso’s figurative work of the early 1930s and Hepworth had met Picasso in France in 1933. She also met also Brancusi whose radical simplifications are echoed in her work thereafter, but others influenced her too. Her Mother and Child of 1934, for instance, is very close to work by Jean Arp from a year or two before.

In 1933, Hepworth herself, Henry Moore, Paul Nash, Ben Nicholson and Edward Wadsworth formed a group called Unit One reflecting this ongoing dialogue with the new European modernism. In a fascinating archival display there is, for instance, a letter to Hepworth from Mondrian in Paris in 1936. Two years later he came to London. The rectangular pattern of a rather beautiful printed fabric that she designed in 1940 seems to reflect his work, or at least the principles on which it was based.

In 1936, the first Surrealist exhibition in London added something more subversive to the mix. Reflecting these new directions, in the later thirties Hepworth’s work includes both geometrically abstract works like Two Segments and Sphere, which, in white marble, is just what it says it is, and Standing Figure. The latter is also abstract, but rather than geometric, reflecting the Surrealist interest in the mystery of the subconscious, it somehow seems strangely animated as though a neolithic standing stone was inhabited by a mischievous surrealist sprite.

Advertisement

Hide AdWork like this, or Two Forms in Echelon, two slender, standing shapes in polished wood, dark as bronze, also reflect the interest in standing stones that Hepworth shared with Paul Nash. One of the elements of Two Forms in Echelon also has a hole in it, a sculptural device that had first appeared in her work in 1932 and which she used frequently thereafter, saying how she loved the idea of people seeing through her sculpture.

Her marriage to John Skipping broke down. Ben Nicholson became her second husband and in 1934 she had triplets, two girls and a boy. She had already had a son with John Skeaping and in August 1939, the Hepworth-Nicholson family moved to Cornwall which remained her home thereafter. With her young family to look after, little money and the difficulty of finding material in the war, (she had to have a permit to buy wood) she couldn’t make much sculpture, but she did not give up her art and spent her evenings drawing, mostly what she called “sculptures in the disguise of two dimensions” – geometric compositions of straight lines and curves that echo her first use of stretched string and wire in her sculpture. She also made work in plaster, however, and in spite of the difficulties of wartime, had her first one person show in 1944 in Wakefield.

Advertisement

Hide AdOne of the most striking group of works here followed an invitation in 1947 to draw in a hospital. The resulting drawings of surgical teams in the operating theatre have real grandeur that echoes classical Greek sculpture. Her interest in ancient Greece is also seen in her designs for a production of Sophocles’s Electra at the Old Vic in 1951. She cooperated with musicians and composers, too, and made work inspired by music. Rhythmic Form from 1949, for instance, is linked to Stravinsky in the label here. It is a simple standing form with an elegant curve that follows the wood grain. A single hole cut through it opens it up spatially as though music translated into dance was then translated into sculpture.

Movement did then become very much part of her vocabulary, especially in a group of gestural paintings that seem to have been inspired by abstract expressionism. The sea was visible from her studio and the movement of the waves is echoed in work like Sea Form (Porthmeor) from 1958. It is in bronze and she worked increasingly in metal to produce large, often curvilinear compositions which were often for public commissions or outdoor display. Open Curved Form from 1961, for instance, is composed of ribbon-like shapes in interlocking curves. Like a number these later works it is in patinated, but unpolished bronze. Working on a bigger scale and modelling rather than carving, she lost something of the intimate relationship with her material that makes her finest work so exquisitely beautiful. Her work on paper lost none of its freedom, however. Genesis III from 1969, for instance, a red and a black disk floating against splashes of black, is free and vivid.

Online, Dressing Above Your Station is an exhibition staged in a digital Tramway. (Tramway never looked so good, but I did find the digital experience slightly tricky, my fault no doubt.) The show explores a single aspect, dress, in all the diverse richness of Steven Campbell’s art. One of the finest and most inventive painters of his time, this virtual exhibition sets out to present something of his inimitable sense of style. Clothes matter in his pictures. His hikers usually wear Harris tweed and his own clothes were unconventional but carefully chosen. Here a dozen or so assembled works reflect these interests, but the leading act is a commentary from Carol Campbell, better qualified than anyone to illuminate the sometimes dizzying complexity of her late husband’s art and the range of reference that he brought into it.

Barbara Hepworth until 2 October; Steven Campbell until 26 June, see www.dressingaboveyourstation.com

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions