Art review: The Turner Prize 2023, Towner, Eastbourne

The Turner Prize 2023, Towner, Eastbourne ****

This year the Turner Prize circus moves to Eastbourne, a coup for the local Towner art gallery which is celebrating its centenary. This has brought much excitement to an East Sussex town better known as a fading seaside resort and a haven for retirees. Its arts community has leapt into action with an ambitious wraparound programme of contemporary art around town, Eastbourne ALIVE.

The gallery itself, which moved to a new building in the centre of town in 2009, has cleared most of its permanent collection (it is known for 20th-century British art) to make room for the Turner. The four shortlisted artists have a spacious room each which, given how different they are from one another, operate almost as four separate shows. The winner will be announced in Eastbourne on 5 December.

Advertisement

Hide AdIt’s hard to think of four more contrasting practices, ranging from meticulous pencil drawing to large-scale conceptual installations of found materials. What unites them is a certain engagement (albeit in very different ways) with the moment in which we live, and with the question of what it means to make art in the world today.

First up is Ghislaine Leung, whose work might be the toughest in the show. Dominating the space is Violets 2, a gargantuan section of ventilation piping removed from a pub in Belgium in 2017 after a public smoking ban. Next to it is Fountain, a cascade of water in a steel drum which, we’re told, is for noise cancellation purposes, though the effect it has is to fill an otherwise quiet space with noise.

Leung’s particular mode of art-making is to create “scores” – written ideas which are then realised in different ways by installation teams in each iteration – part of her ongoing desire to highlight the labour and support structures around making art. She’s also interested in what it means for her to make art as a woman and a mother: Hours, a black and white wall grid, illustrates the limited amount of time per week she is able to spend in her studio.

It’s a somewhat incongruous group of things, however: big industrial piping next to a baby monitor (linking to the gallery’s art store) and a line of toys borrowed from a local library. It’s not clear what she’s communicating, particularly with the ventilation pipes, which take up most of the space.

Rory Pilgrim’s RAFTS was realised during the pandemic along with eight members of Barking & Dagenham organisation Green Shoes Arts, which offers arts programmes to disadvantaged and vulnerable people. The raft becomes the central metaphor for reflections on what keeps us afloat through difficult times.

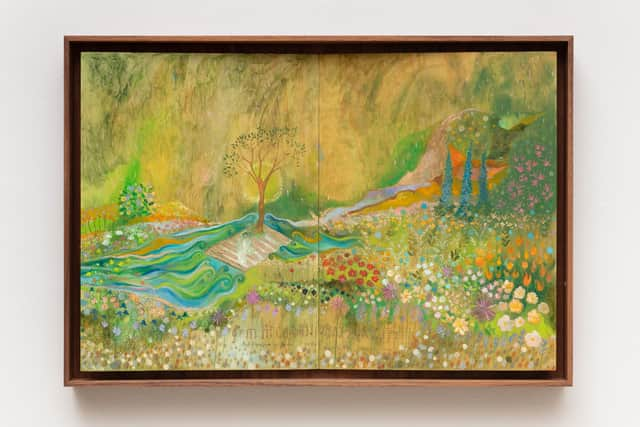

The result is a film of Pilgrim’s seven-song oratorio, performed by the London Contemporary Orchestra, interspersed with performances and interviews by the eight collaborators who celebrate their own creativity in photography, painting, poetry and animation. A second film shows a live performance of the same material in Cadogan Hall (both are about an hour long). Small jewel-like artworks, by Pilgrim and some of the eight, adorn the walls of the space, naive but rather beautiful.

Advertisement

Hide AdWhile there’s some excellent singing by Declan Rowe John and Robyn Haddon, and a strong routine by Barking & Dagenham Youth Dance, the film is heavy on inspirational jargon – creating your own sunshine, finding joy in nature, becoming the person you want to be – which is either sincere and tender or schmaltzy and clichéd, depending on your point of view. However, whether or not you can fully buy into it, Pilgrim succeeds in giving voice to ordinary people for whom creativity has been a lifeline in precarious times.

In that sense, RAFTS could be understood as a series of portraits in which the subject and artist collaborate, and there are more portraits, in the more traditional sense, in the work of Barbara Walker. She celebrates another community, in this case people affected by the Windrush scandal who arrived from the Caribbean between 1948 and 1973 and suddenly, from 2017, found themselves wrongly classified as illegal immigrants, forced to dig up decades-old paperwork to prove their right to remain.

Advertisement

Hide AdWalker’s pencil portraits, Burden of Proof, layer images of individuals with pencil drawings of the documentation which came to represent them, as red tape cut across personal stories. Her work, though it might suffer on this shortlist for being seen as too literal, has the effect of restoring the individual stories: an exemplary service record from the (British) Army; a glowing testament from a Birmingham school to the work of its classroom assistant.

However, her work does more than make individual stories visible, it makes them monumental – five of them, at least – in a set of large-scale charcoal portraits which take up one large wall, another example of how this Turner Prize is making art from ordinary lives.

Finally, we arrive at the work of Jesse Darling, who presents a significant group of new and recent sculptures around the theme of Britishness. It’s a vision of a post-Brexit Britain in crisis, going by the predominance of pedestrian barrier fencing, barbed wire, incident tape and tattered union jack bunting.

Several large pieces set the tone: a maypole, adorned with incident tape instead of ribbons, a steel ladder bent into a rollercoaster which bursts out of a wall (perhaps referencing Eastbourne’s past as a seaside resort), a humanoid “Gorgon (Britannia)” with feet made of jittery stacks of lever arch files, desperately waving union jacks made from tea towels. Everything feels on the edge of collapse, barely holding together.

There are so many smaller works that this show could use a bit more room to breathe: hammers bound with ribbons and bells, as if they belonged in a particularly fearsome Morris dance; a series of clay works which depict hands, cupping water or seeming to reach out in plaintive gestures (called Covenants); humorous “Grandad” personages made of crutches and walking sticks, bells and candles; dusty lever arch files (Epistemologies), their contents calcified into concrete.

Almost everything here in some way references the human figure. Metal barriers become anthropomorphic. A cluster of porcelain torsos on a shelf is titled Inflation. They speak, perhaps, to the costs of the current moment both on individual bodies and the decrepit body politic. While the space is somewhat overcrowded, Darling is the artist who creates the most vivid visual metaphors for the state we’re in.

Advertisement

Hide AdIf the Turner Prize is a snapshot of contemporary art in Britain, perhaps this year’s key word is “fragility”. From Darling’s rickety structures to Walker’s ephemeral wall drawings, from the fragile resilience of Pilgrim’s raft, and the tentative propositions of Leung’s “scores”, they speak to a world in which little is certain, not financial or personal wellbeing, nor one’s right to citizenship, nor even one’s right to make art. Art, then, must question everything, even itself.

Until 14 April 2024