Art review: Tartan, V&A Dundee

Tartan, V&A Dundee *****

Tartan is a chameleon, a shape shifter, endlessly variable both in its coloured patterns and in the purposes it serves whether clan, army, or nation, the grand, or the humble. Beloved of kitsch, it has been both a punk symbol of protest and inspiration for the elegance of haut couture. It is these contrasts that provide the text for Tartan at the V&A Dundee. In the words of the press release, the exhibition “highlights the ways tartan shapes identities, embraces tradition, expresses rebellion and conjures fantasy.” Correspondingly there is as much of the whacky and weird as there is of the straightforward story of tartan.

The show begins with an intriguing account of the mathematical basis of tartan and how with the simple opposition of the vertical and horizontal threads on a loom, the warp and the weft, it can build patterns of wonderful complexity and variety. This appealed to abstract artists and even to architects and a piece of tartan glass by Cathryn Shilling, transparent but folded like a cloth, does give a vivid idea of the spatial quality of the fabric. Architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh designed a black and white chequerboard fabric. It is not altogether clear that it derived from tartan, but the same pattern was adopted by Glasgow police and thence became the identifying symbol of police everywhere.

Advertisement

Hide AdMuch of the story of tartan is told here in little bits and pieces of cloth, whether in a weaver’s record of his work, or a manufacturers’ sample library. Jurgi Persoons has made a kilt entirely of such little pieces. It looks like an epitome for the show but it actually dates from 2001. There are also nineteenth-century books of tartans incorporating real cloth or coloured images and put together to classify tartans by attributing specific patterns to particular clans. A self-portrait of artist Andrew Robertson identifies him as one of the principal originators of this largely spurious codification. He wrote around asking for samples of family designs. Dependent on the whim of his correspondents, the whole thing became an earnest fabrication, but it had traction. Playing to our need for identity in a fluid world, clan tartans are bigger business now than they ever were in the past.

Robertson’s initiative was part of the revival of tartan. Because it was a unifier and identifier of the Highland people – and it is pretty clear they wore it, mix and match, exactly how they liked – it was proscribed after Culloden. Worn by his Highland troops and indeed by Bonnie Prince Charlie himself, it was indeed a symbol of rebellion. Some defied the proscription, however, and one of the loveliest things here is the wedding dress and plaid of Isabella MacTavish worn when she married in 1785.

Highlanders recruited into the army were exempt from this proscription and their tartans were turned into uniforms. Cartoons from Paris after Waterloo demonstrate that what the soldiers wore under their kilts was already a matter of pointed curiosity for the ladies. Queen Victoria’s faithful John Brown’s tartan drawers provide one answer. Fashion plates show that the French ladies also wore tartan themselves with great panache, however.

But the military kilt is a tight and constricted thing. The magnificent portrait of Lord Mungo Murray painted by Michael Wright about 1683 shows how tartan should be worn with kilt and plaid in a single flowing garment. Although it became famous because of the rebellion of the ‘45, tartan is not inherently rebellious as the show seems to imply. It is just a type of weaving pattern after all, but the rigid conformity of the military kilt that has become the standard of how it is worn, by men at least, denies its inherent elegance and so does perhaps invite disruption. Some of the early fabrics and garments are really beautiful, however, especially when “hard tartan” is used. (I did not find an explanation, but this is apparently woven from worsted wool spun more finely and more evenly than “homespun.”) In the nineteenth century a dress designed for Queen Victoria and another for Queen Alexandra show, too, that both the elegance and the political significance of tartan were well understood.

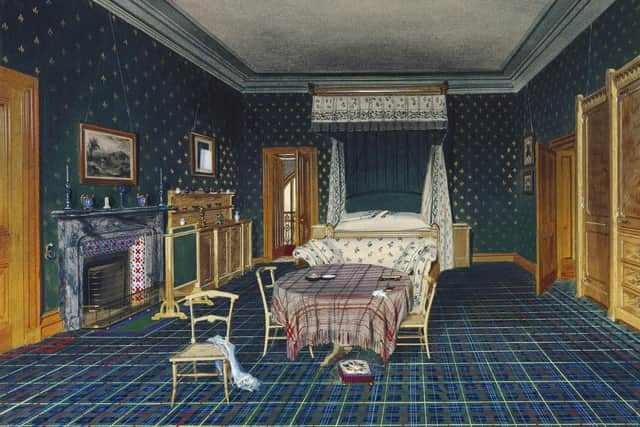

Queen Victoria’s tartan bedroom at Balmoral is definitely overkill, but exquisite garments designed by Jean Patou, Coco Chanel, or Christian Dior show that in the hands of genius tartan can still be supremely elegant and has no need to be undercut by arch self-mockery. The exhibition seems nevertheless to attribute recognition of its potential to the punk non-conformity of modern designers like Vivien Westwood. The Bay City Rollers also get a reference here, but it is debatable whether their use of tartan was punk or national pride. Alexander McQueen designed a Highland Rape collection in his own tartan “to commemorate the suffering inflicted by English landlords on Scottish Highlanders,” but the sexy elegance of his designs seriously confuses that message. There is a “tartan eleganza” drag suit worn by Violet Chachki which is indeed elegant and a pair of tartan codpieces designed by Marcel Duchamp which certainly are not. With three hundred exhibits there is a huge amount of diverse information to absorb. Tartan is not exclusively Scottish and its use in cultures in India and Africa is acknowledged here, for instance, while exhibits range from tartan-edged comic postcards and tartan plastic bags to the first ever colour photograph, a piece of tartan ribbon photographed by James Clerk Maxwell using three colour filters.

The earliest surviving piece of Scottish tartan is here. Dated to the sixteenth century, it was preserved by the peat in a bog in Glen Affric. The exhibition seems, however, to overlook the significance of the earliest precisely dateable item on view. It is a reference in an account book to clothing made of ‘heland tertane’ for King James V in 1538. That it is identified as Heland is surely significant here for it suggests that the tartan identity of the Gaels was by then already well established. But the show doesn’t seem to query why the king would have wanted tartan clothes in that year in particular. The answer might be that it was in June 1538 at the Palace of Linlithgow that he welcomed his new wife Mary of Guise to Scotland from France where they had earlier been wed by proxy. James was a pretty stylish monarch and while we have no proof, the date does forcefully suggest he dressed in brilliant tartan to meet his bride, just as so many Scots have done ever since. He would have made a splendid figure and would surely have impressed his new wife, but his tartan suit was making a political point too. It was only recently that royal authority had been established in the wider Gaeltacht. It was still precarious, too, and whatever the occasion may have been in fact, in his suit of Highland tartan James V was declaring himself king of both parts of his bilingual kingdom. That said, Gaelic may now be beleaguered, but it is pretty poor that in a Scottish national institution this show about tartan, the definitive costume of the Gaels, though visually it is wonderfully rich, has not a single word of Gaelic in the labelling and information panels.

Tartan, V&A Dundee, until 24 January 2024