Art review: Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer, V&A Dundee

Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer, V&A Dundee ****

Once upon a time, museums were reverential places: ordered, circumspect and above all, quiet. None of this is true about Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer, which has just opened at the V&A Dundee. It comes at the viewer – and at its subject – from all angles, and it pulsates with sound.

That said, it would make no sense to tell the story of Michael Clark in po-faced silence. A kind of real-life Billy Elliot, he turned the ballet world upside down in the 1980s with rock music, outrageous fashion and a fearless punk energy, all the while retaining the technical virtuosity, poise and precision of his classical training.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe opening of the show in Dundee brings Clark’s story close to where it started (he grew up in Aberdeenshire). But the true locus of the story is London, where he went at 13 to take up a scholarship at the Royal Ballet School, and where, by the early 1980s, he was immersed in the gay scene, club culture and the energy of punk. Curator Florence Ostende pitches the show well, creating a trip down memory lane for those old enough to remember, and a colourful introduction to the time for those who are not.

Capturing dance in a museum is always going to be challenging. The art form is ephemeral, and while you can exhibit costumes, sets and even film, it still leaves the viewer with the unshakable feeling that the party has already happened elsewhere. At least we’re left in no doubt about how good a party it was.

Clark formed his own dance company in 1984 at the age of 22, dressing his dancers in costumes by Leigh Bowery and BodyMap, choreographing to The Fall, Bowie and T-Rex. The energy of those early years is captured in the first, and largest, space, in a loud multi-screen installation by long-time collaborator Charles Atlas, chopping up and re-editing his two films about Clark, Hail the New Puritan (1986) and Because We Must (1989).

Described at the time as “fictional documentaries”, they mash-up dressing rooms and nightclubs, ballet classes and costumes and candid chat until performance and real-life are indistinguishable. That’s the point, of course. There was no distinction, and everything happened in bright colours, at full volume. Clark was consciously creating a spectacle, on and off stage.

While the show is broadly chronological, it feels more like everything is unfolding in a loud and continuous present. The exhibition is not overburdened with costumes and sets, though there are a few: Bowery’s designs for I Am Curious, Orange, and the giant burger and fries Clark designed himself, BodyMap’s dinosaur costume which Clark wore in Because We Must.

The company’s work is mainly recorded in film; TV monitors literally spill out of the exhibition space into the foyer. There are so many, in fact, that it’s possible to miss the rarest gems. There are a lot of interviews too, including a memorable Walkie Talkie (the chat show with legs) with Muriel Gray from 1989 in which Clark wears a kilt and a Chanel headscarf. Sadly, the biggest screens rarely show dance, though when they do it looks spectacular.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe artist Elizabeth Peyton (whose portraits are shown here) said of Clark’s early choreography: “I never saw anything truly total like that before… I’d never seen a dance work that held this/our time somehow with no filter.”

Spending time in the exhibition, one begins to discern something underneath the noise and the spectacle. It would be easy to see Clark’s work as pure hedonism (he did one say he believed it was the duty of an artist to explore altered states and report back), but he had a very clear idea what he was rebelling against.

Advertisement

Hide AdWhen he clothed his dancers in costumes with cut-away bums, he was fighting a ballet aesthetic which turned dance into something prim and asexual. In a wider sense, he was fighting the conformity and conservative values of Thatcher’s Britain, its homophobia, its hyprocrisy towards the working-class. He was celebrating queer culture, challenging gender norms long before this became de rigueur.

His work engaged with issues, from junk food to police brutality. I Am Curious, Orange was created for the Holland Festival in 1988, responding to the 300th anniversary of the coronation of William of Orange, and featured dancers in Rangers and Celtic strips. Meanwhile, Mark E Smith’s lyrics took on the Troubles, colonialism and Aids.

Wrong, made by Clark and his then partner Stephen Petronio for the South Bank Show in 1989, is a glorious pop-art influenced mash-up of the moment, name-checking Myra Hindley and Leon Britton, the Hillsborough Disaster, apartheid, clause 28 and the death of the rainforests. Around the same time, he made one of his most intimate works, Heterospective, which included a solo, Heroin, in which he danced in a white body suit with needles attached.

The show tells his story through his collaborations: Bowery, Peyton and Smith, and the artist Sarah Lucas, who designed the notorious masturbating arm for Before and After: The Fall (2001), and later made Cnut, a concrete cast of Clark’s body (cut off at the shoulders) sitting on the toilet smoking a cigarette. There are photographic portraits by Wolfgang Tillmans, who manage to find a fresh, intimate take on this much photographed man.

There is a painting by Peter Doig, Portrait (Corbusier) 2009, lowered onto the stage during Come, been and gone, shown alongside 16mm footage filmed by Clark himself of the company dancing on the roof of a Le Corbusier apartment block in Marseilles.

More recent work includes paintings in response to his work by Silke Otto-Knapp, and It for others, the 2013 film by Glasgow-based artist Duncan Campbell, for which Clark created choreography representing the economic equations in Marx’s Das Kapital.

Advertisement

Hide AdIt’s a show which struggles to find an ending, which is appropriate because, despite the fact that it feels like a tribute at times, Clark is very much alive – turning 60 this year – and still working. That said, his voice is an absence in the exhibition, which adds to its elegiac quality. Indeed, there are few voices in the show who are close to him. As tributes go, it’s oddly circumspect.

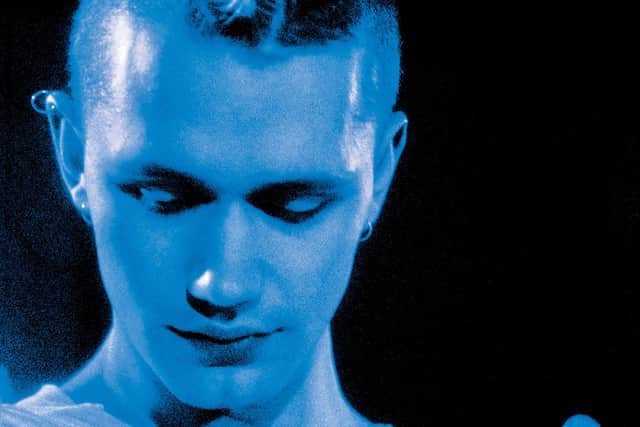

One leaves with the sense of the bad boy of ballet as a restless, questing intelligence (a reading list in the catalogue includes Camus, JG Ballard and James Joyce). And although Clark’s image is everywhere in the show, his compelling elegance little changed by the years, the essence of the man himself is strangely absent. Not inappropriately, we see his plural selves, hard to pin down, perpetually in motion.

Advertisement

Hide AdUntil 4 September, see https://www.vam.ac.uk/dundee/exhibitions/michael-clark-cosmic-dancer

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions