Art review: Graduate Show 2021, Edinburgh College of Art

Graduate Show 2021, Edinburgh College of Art ****

This year’s ECA degree show is a pretty minimal affair, but in the circumstances it is a remarkable achievement that there is show at all, and even more that the students have managed to produce good work for it. Their circumstances really have been challenging. With very limited access to the studios, and only for some students, they have had to work wherever they can find space – in their bedroom, in the garage, the garden, or wherever else. And where they have worked at home in whatever space they could find, inevitably all sorts of other pressures must have arisen. Meanwhile, those who opted to come to town, if not to college, faced similar problems whether in rented accommodation or halls of residence. In the latter, as my guide round the show remarked, they couldn’t even put a drawing pin in the wall. All the teaching has had to be online, too. It has been a really taxing social, intellectual and artistic obstacle course, and yet they have come out of it with flying colours.

Kayna Macaulay's year not-at-college, as it were, seems to have been typical of many. She had to retreat to her family house in Cornwall which, she says, “my dad has been self-building” for a number years – a building site in fact. Nevertheless, she has made some beautiful abstract designs using found materials. These are represented in the show by a handsome digital print. Muriel McIntyre’s circumstances, too, seem to have shaped her work. “I completed my Fine Art degree in my parents’ basement in France, the abandoned wine cellar,” she says. Inspired by this, her work explores abandoned spaces in different ways. Nothing is more eloquent of her dislocation, however, than a steel chair simply cut in half vertically and its two halves, left and right, transposed. There seems to be something poignantly relevant, too, about the inspiration behind Roisin Pharncote-Rowe’s miniature beds in iPhone boxes. They were inspired amongst other things, she says, by “bad furniture in rented flats.”

Advertisement

Hide AdMhairi McPhail explores a domestic theme which it seems might also reflect her circumstances, at least implicitly. A rather beautiful installation suggests the hearth as heart of the home, but a target hanging at its centre proposes the domestic sphere as battleground. And in this battle she weaponises “hostess soap” in the form of the spearheads of cast iron railings. With enterprise typical of this group, she also organised a “washing line exhibition” in her back garden.

Fruzina Uhlar’s enormous whirling, long-haired wig is a dramatic piece of sculpture while two rather organic looking latex moulds suggest hers is a feminist theme. Nearby Jamie O’Donnell has made a really striking piece of stop motion animation. Two figures explore the inner workings of a human body and seem to compete there, too, apparently reflecting aspects the artist’s own experience.

Katherine Benson is an exquisite painter, but in miniature. She doesn’t say if her choice of scale is dictated by her circumstances, but her biggest pictures are just a foot across. Others that she calls miniatures are just three or four inches. Her subject matter is women in domestic interiors. It is an iconography that recalls Bonnard or Vuillard, but hers are definitely women away from the male gaze and they have an unusual, delicate intimacy. In spite of the small scale, she paints freely, but with a light touch and a lovely sense of colour which all adds to the feeling that she is celebrating her subjects.

Calypso Keightley seems primarily to be concerned with fast fashion and its environmental consequences. She poses in the woods in a ragged dress made from polluting fabrics, but intriguingly she has also gone in a rather different direction, first to construct and then make a rather beautiful painting of a set of 16th-century women’s stays, a peculiarly constricting garment and so implicitly a feminist image. She also poses in them. Lorena Levy is another remarkable painter. Her work is based on her austerely beautiful drawing and belongs more or less in the realm of strongly characterised portraiture. It also leans rather enigmatically towards narrative, however, if only because her paintings are almost all of pairs or groups of people. She works on unprimed board. This has the odd effect that her figures seem to float as much in a mental space as a pictorial one. This in turn seems like a metaphor for what she says about using the internet for company in lockdown.

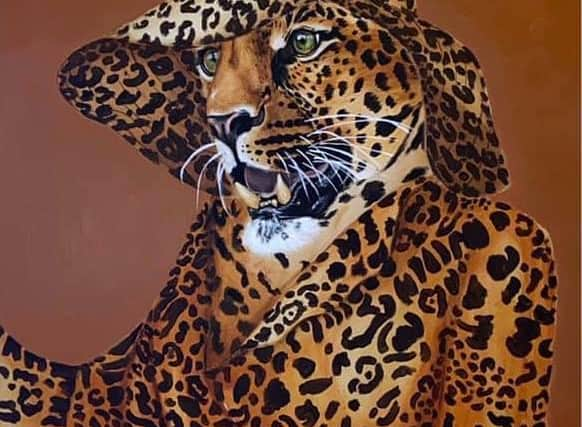

Elle Johnson makes fashion images out of leopards, not from their skins, but using fashion models that are leopards. The result is a startling set of images, though she also uses the leopard motif to create more conventional pattern repeats. In a series so paintings of fragments of construction Oscar Mateos explores the little-known story of Fascist concentration camps near Seville and the canal that Franco’s prisoners built as forced labour there. The erasure of the public memory of such things is also part of his theme.

The Sculpture Court, the College’s principal space, is dominated by a huge wooden slide made by Campbell Gittens. Accompanying images make it clear that he has had to work in the garden and the garden shed, but the results are impressive. He has not only made the slide, but also a life-size, jointed wooden figure that slides down it. It also mows the grass, or at least in a film it is dragged along behind the mower. The consequent semi-animation has a rather spooky effect. Sophie Templeton matches the scale of Gittens’s slide with a ten metre drawing draped over the balcony. Nearby Otto Gobey deploys a contrasting economy of means in a spare but rather elegant three-armed wooden cross.

Advertisement

Hide AdAlso in the Sculpture Court, Andrew Packham’s Human Construct is one of the most striking objects in the show. It is an enormous head standing on the ground. A rough, modular construction, grey painted, it has echoes of both Eduardo Paolozzi and Easter Island figures, but little staircases leading in and out also suggest a kind of vertical labyrinth in human form, or some strange totemic building.

There is much else of course. Most of the show is online, but the actual degree show, though minimal, is certainly worth seeing.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe Edinburgh College of Art Graduate Show 2021 runs until 25 June, https://www.graduateshow.eca.ed.ac.uk/

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions