Art review: Eastern Encounters, Queen's Gallery, Edinburgh

Eastern Encounters, Queen’s Gallery, Edinburgh ****

A bit like flowers in spring, the galleries are gradually reopening. The private galleries are almost back to normal, but the public galleries are being a bit slower. We don’t have a date yet for the reopening of the National Galleries of Scotland, except that we are told it will be August. Of course for the galleries in general, the cancelling of the physical incarnations of the Edinburgh International Festival and the Fringe and the planetary system of festivals that surround them – particularly the Edinburgh Art Festival – is like cancelling Christmas for the toyshops. The greatest loss of all in the visual arts, however, is the cancellation of the exhibition of the Titian Poesie, or mythologies, the six astonishing pantings with subjects from Ovid that Titian painted for Philip of Spain which should have come to the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh. They include of course Diana and Actaeon and Diana and Callisto. They hung in the National Gallery for 50 years until the Duke of Sutherland sold them and the National Galleries of Scotland and the National Gallery in London bought them as a shared purchase. The six pictures were planned to be seen together, but they haven’t been seen that way for 400 years. They stand at the very fountainhead of western painting. It would have been a unique opportunity to see them together as the artist intended, but they are being shown in London and will be in Madrid and Boston but not now in Edinburgh. We know our place.

Some promises have been kept, however. The Queen’s Gallery was on the point of opening Eastern Encounters when lockdown happened. Open now, the Royal Collection deserves credit for being the first of the major public galleries to open its doors. The exhibition is of painting from the Indian subcontinent. The artists and calligraphers who worked for the Mughal Emperors in the late 16th and 17th centuries produced some truly glorious art. Their style is essentially Persian, and there were very close links with Persia, but there was also interaction with European models. One lovely little painting of the Madonna and Child is based on a Dürer print, for example. Although they were Muslim, portraits feature very significantly in the art of the Mughals and a collection of portrait miniatures do look strikingly like their western equivalents, but the influence could perfectly easily have been from East to West.

Advertisement

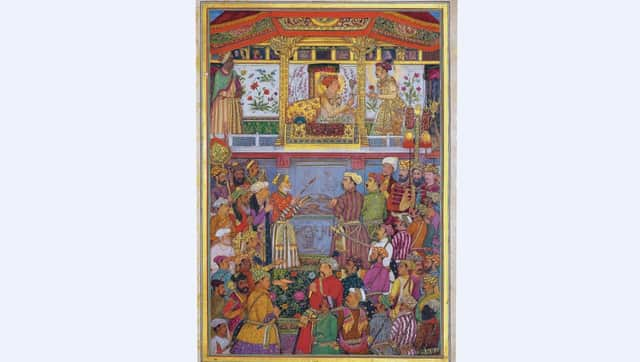

Hide AdThe star of the show, however, is one of the finest of all Indian manuscripts, a volume of The Padshahnama or Book of Emperors, commissioned by the Emperor Shah Jahan, also responsible for the Taj Mahal, “as a propagandist celebration of his reign and dynasty.” Propaganda was rarely so beautiful. What we have here is one volume of three and there are signs that it may also have been left incomplete when Shah Jahan was overthrown by one of his sons. It is, however, the only Imperial copy of the manuscript to survive with all that that implies in richness and quality both of painting and calligraphy. It opens with a portrait of Shah Jahan himself sitting face to face with Timur, or Tamurlaine, from whom the Mughals claimed descent. The painted pages that follow include hunts and battles, but what are really striking are the court scenes. Exquisitely painted and composed and brilliantly coloured, they give us a sense of the astonishing richness and sophistication of the Mughal court.

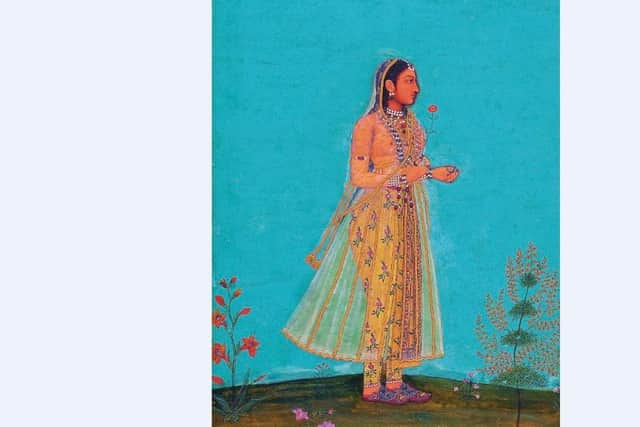

Nor was court life all politics. Among the other works here are lovely illustrations to poems and scenes of romance. One charming example shows the story of a great musician, Madhava Nal, fainting at the sight of Kama Kandala, a courtesan famous as he was for her singing but also for her beauty. A nayika waiting for her lover, half naked against the night sky, is a gorgeous erotic invitation. It was to this glamorous and sophisticated court that Sir Thomas Roe was sent as English ambassador by James VI and I in 1613. Poor Roe complained about the gifts which he had been given to present to the Emperor “that they laugh at us for such as we bring.” He and his sovereign from a small misty island far away were quite outclassed.

Shah Jahan’s empire encompassed most of the Indian subcontinent. Its wealth and power far outshone any European kingdom. Along with China, the subcontinent was at the time the world’s principal source of manufactured goods, particularly textiles. It was a honeypot for European traders. Eventually, after fighting with most of the others, especially the French, the British East India Company became the most powerful, exploiting and also promoting the increasing fragmentation of the once unified Mughal empire to seize control of most of the subcontinent. Eventually passing from the Company to the Crown, it became the British Raj and Queen Victoria its Empress. In this long story gifts of various kinds, often of astonishing richness, came from the rulers of the Indian states to the British Crown, usually with a letter expressing the donor’s hope of some intervention on their behalf against the rapacious East India Company. These letters are themselves things of beauty. Azim Jah wrote to Queen Victoria, not to ask a favour, but to offer his condolences on the death William IV and corresponding congratulation on her ascent to the throne. His letter is written on a page of gold. Over the 300 years over which the work here ranges, the quality does decline, but the show ends with a lovely painting of Queen Tisarashita by Abinindranath Tagore, a founder of a new nationalist school of painting at the beginning the last century.

We are assured that only two items here are actual spoils of war. Nor was everything else a gift. Individual monarchs did collect and indeed Queen Victoria became so enamoured of her distant empire that in her old age she endeavoured to learn Hindustani. Nevertheless, the whole collection does reflect the slow, corrupt process by which the once great Mughal Empire became the British Raj. The art is glorious, but indirectly it does illustrate a rather shabby story, though one the show and its catalogue tell very well.

Until 31 January 2021