Art review: Alberta Whittle: create dangerously, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh

Alberta Whittle: create dangerously, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh ****

Occasionally, an artist comes along whose work fits so seamlessly into the current moment that their rise becomes unstoppable. When she won the Margaret Tait Award in 2018, Alberta Whittle was a well regarded but largely unknown graduate of Glasgow School of Art’s MFA course who had never had a big solo exhibition.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn the last five years, she has won the Frieze Award, a Turner Prize bursary (in 2020 when the prize was cancelled), has had her work selected for British Art Show 9 and has represented Scotland at the Venice Biennale. Now, she is the subject of a major solo show at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art.

To make this point is not to cast aspersions on the quality of Whittle’s work, or her commitment to it, which is unarguable. It’s just that an artist’s success does not only depend on these things; it has to do with context, both in the art world and in wider society. In a world worried about racism, climate change and the shameful but inescapable history of colonialism, Whittle’s work arrived like a welcome thunderstorm. Not only was she unafraid to address difficult issues, she confronted them in a way which invited her audience to collaborate on a solution.

This major solo show, curated by Lucy Askew and occupying the entire ground floor of Modern One, is the homecoming of her Venice Biennale work, but was always intended to be much bigger. The film which was the centrepiece in Venice, Lagareh – The Last Born, is at the centre here, too (albeit on a strangely small screen) but with a much larger and more diverse body of work flowing around it. This is the most comprehensive insight we have had to date into Whittle’s multidisciplinary practice.

Until now, we have encountered her principally as a maker of films, which are the most immediately responsive and overtly political of her works. Given how prolific her film output has been in the last five years, it is surprising to find just two in this show, Lagareh and Holding the Line: A Refrain in Two Parts, which deals with (among other things) the treatment of people of colour during the pandemic. Most of the rooms, which are painted in glorious shades of purple, green and blue, house watercolours, oil paintings, digital collages, sculptures and textile pieces.

Whittle started making films in 2017 because she wanted to address immediate events, having witnessed first hand the Rhodes Must Fall movement during a residency in South Africa. Propelled forward by the events of the Windrush scandal and Theresa May’s hostile environment, she had more and more she wanted to say. Coming from the Caribbean, the history of slavery was already present to her. Then came George Floyd, Black Lives Matter, and the disproportionate number of black deaths from Covid-19.

Collage is her driving aesthetic, and her films work by collage and juxtaposition. On the one hand, she presents uncompromising footage of real events – police in riot gear turning on BLM protesters, a black man being stopped and searched during lockdown – but these are balanced with more meditative moments: often movement, voice and ritual enacted by Whittle herself or her “accomplices”, an extended family of black artists, writers, and musicians.

Advertisement

Hide AdLagareh – The Last Born is the most ambitious manifestation of this approach. Filmed in Sierra Leone, Barbados and Scotland, it interweaves the history of slavery with the present day story of Sheku Bayoh, the 30-year-old man who died after being restrained by police in Kirkcaldy in 2015. A dancer intertwines with a snake; another expertly wields two machetes; musician Kumba Kuyateh sings a power Mandinkan “praise song” for Bayoh in a London court room; a queer couple talk gently about the upbringing they want to give their children. It ends with a litany of names of people of colour who have allegedly died at the hands of the state in the UK and the words “We will remember”.

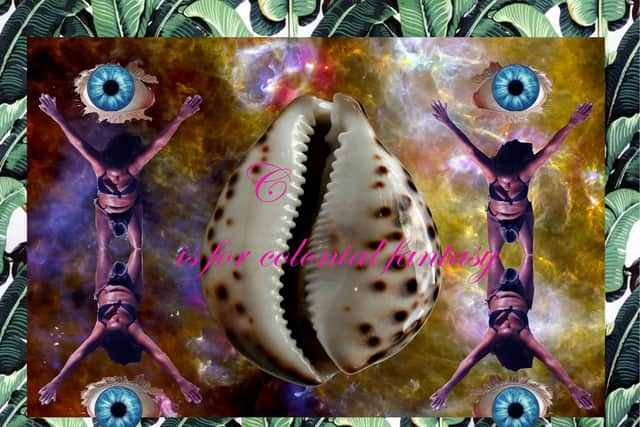

Experiencing Whittle’s wider practice, we see a similar balancing act at play. For every flash of anger – the drawing of a person being seized by three police, the sharply satirical digital collage ‘C is for Colonial Fantasy’ – there is a painting with the words “fill your heart with hope” or a tender portrait of Whittle as a child done by her mother.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe title “create dangerously” comes from Haitian-American writer Edwidge Danticat, who repurposed it from Camus making it into a invitation to the audience to become co-conspirators in an outworking of resistance and hope. A worked example of this is provided in the textile hanging included in the show made by members of Project Esperanza, a charity which supports women of culturally diverse backgrounds in Edinburgh.

At times, there are mixed messages. The ornate iron gates made for Venice will never be anything other than gates: they are always going to speak of confinement rather than freedom. The tapestry made for the Venice show by Edinburgh’s Dovecot Studios, titled Entanglement is more than blood, is a rich collage of imagery, colour and objects (whaling rope, Venetian beads, children’s hairclips, cowrie shells) but it is hard to disentangle its meanings. In the skeins of history, much is tangled which cannot easily be loosed.

What comes through particularly strongly is Whittle’s recourse to the imagery of the sacred in Caribbean and African cultures. Objects take on totemic force, from a cow’s jawbone to a giant sea shell. An installation in memory of the Barbadian poet Kamau Brathwaite is indistinguishable from a shrine. There are portals, rituals, women appear as goddesses, a libation is poured. Mami Wata, the African goddess of the sea, is everywhere. And these are often the moments at which the work is most visually powerful.

The fact is, the force of Whittle’s work – the driving momentum of its engagement with important issues – tends to carry the viewer along. She shifts so frequently between media – from assemblages of objects to bronze casts of the her tongue, from a lifesize Barbadian chattel hour to films and woven textiles – one has consciously to stop in order to consider the effectiveness of each work in turn. Whittle has trained in a context which favours ideas over skill, and while there is much skill here, the fact is that some pieces work better than others.

Her intense concern with looking after her audience, from comfortable seating in the shape of punctuation marks to a room given over to rest with handmade quilts to wrap up in, will appeal more to some than others. Some, I suspect, would prefer the work presented with all its sharp edges, but the additions don’t get in the way. What occasionally does is the tendency to overstate a point just to make sure we get it. Whittle looks after her audience well, but she needs to trust us too.

If her aim is to set out a manifesto to balance the black experience of hostility and oppression, she draws on a powerful arsenal of resources. She presents a vision of black culture which is both ancient, drawing on deep roots which go back beyond white interference, and one which is young, strong and full of imagination. Seeing it as a white person, one can’t help but be reminded of one’s complicity in systems of oppression. Yet there is no brow-beating, just a gracious invitation to live differently. Yeah, it sucks, Whittle seems to say. But we got this. Join us.

Until 7 January 2024