Art reviews: RSW Annual Exhibition | Gary Fabian Miller | The Archive of Modern Conflict

The Royal Scottish Society of Painters in Watercolour 137th Open Annual Exhibition, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh ****

Gary Fabian Miller: Voyage, Dovecot, Edinburgh ****

Collected Shadows: The Archive of Modern Conflict, Stills, Edinburgh ***

Advertisement

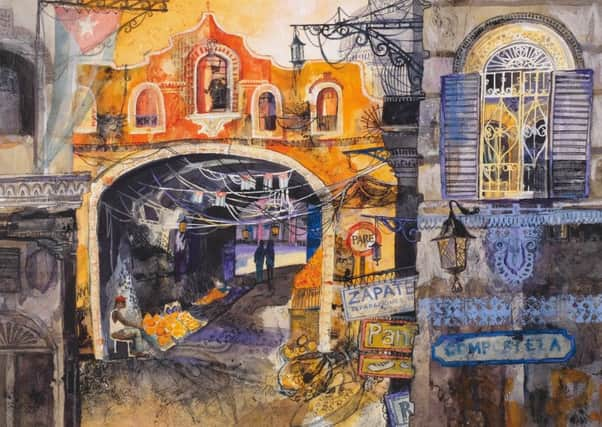

Hide AdThis year’s exhibition is in the lower galleries of the RSA. It is a space that suits the relatively small scale of works on paper. Some artists exploit the luminosity of the medium. Sylvana McLean, for instance, has a picture which she calls simply Luminescence. It is monochrome with light reflected on water beneath a dark sky. Beneath the Flow, by Susan Macintosh shows off all the qualities of watercolour and indeed of paper, its inseparable partner. A big sheet of paper hangs free and unframed. On it the artist allows the paint to flow and puddle and stain while the white of the paper provides a unifying light. Ian McKenzie Smith is a past-master in exploiting these qualities of watercolour. Night Tree is a diptych of a shadowy tree against a luminous, dark blue sky. Alison Dunlop has made an art form out of what seems little more than a single, arching brushstroke of transparent blue, but enlivened by all the subtle patterns that the pigment makes as the water that carries it flows and dries. Michael Durning’s River Gods of the Damnonii works in a similar way to present a blue paddle steamer casting long shadows across the water. In Rippling Landward, Marian Leven suggests waves and water with only the subtlest touches of transparent grey wash.

Others exploit the extraordinary precision that watercolour can achieve. David Evans’s Two Blush Pears sit by themselves in a softly lit field of grey. Every minute detail of both the fruit and the light that illuminates them is miraculously observed and recorded, but there is no hint of labour. Not to be outdone, James Fairgrieve paints a mango on a dishtowel with equally luminous exactness. Angus McEwan applies the same uncanny minuteness of observation to a roughly made picket fence in Essouaria and to a rusty lock in Locked and Loaded. Jim Dunbar’s Sandra, a painting of an abandoned boat by the Buddon in Angus, is also painted minutely, but with the even light and the flat sea beyond somehow the hyperreal leans towards the surreal.

This delicacy can also be highly decorative. Una Cartolina by Ann Ross is a beautiful example of how luminosity, transparency and delicate colour can create poetry. In Fragment of San Marco, Jean Martin incorporates collage and torn edges of paper to suggest a fragment of memory with a similar poetic effect. Sylvia von Hartmann also deploys beautifully the unique qualities of her medium in Toad Writes a Letter. A handsome toad wearing a wreath of flowers sits with its pen and a spilt bottle of ink amongst a wonderful assemblage of leaves and flowers.

There is much else to admire here. David Forster’s moody poetic landscape Here too she found shelter from the storms (Fabriano, Italy) is a tour de force of observation, but all seen under an uncanny, even sinister, altered light. Neil Macdonald’s view of the little harbour at Cellardyke is likewise at once observed and altered, though in this case towards the sunlit timelessness of memory.

If it seems quaint to persist with watercolour as a distinct art form, tapestry is positively medieval. A labour intensive craft, it is apparently quite out of joint with the times, but nevertheless it continues to flourish at Dovecot in Edinburgh as it has done for more than a century. Nor has Dovecot survived by remaining resolutely anachronistic. On the contrary, the workshop has embraced contemporary art with enthusiasm and remarkable success. The partnership with Gary Fabian Miller is a notable example of this. The latest result of this ongoing collaboration is the tapestry Voyage into the deepest darkest blue. Miller for a long time used the intense colours than can be achieved with dye-destruct photographic paper. It is – or was, for it is no longer manufactured – a paper in which the colour is actually in the paper rather than applied to it in some way. In consequence it can provide intense saturated colour. Exposing this paper directly to light without a camera provided Miller with images of stunning beauty and simplicity. Their iconography looks back to the abstract imagery of Josef Albers or Mark Rothko, but Miller achieves a glowing depth of colour that is unique. The original image for the new tapestry is a near-square divided on the horizontal into two equal parts. The upper part is deep blue, shading gradually to black at the horizon and abruptly to black at the edges. The lower half is in contrast like a glowing light, sunshine-yellow shading to orange.

With great subtlety, the four weavers, David Cochrane, Naomi Robertson, Emma Jo Webster and Rudi Richardson, have translated the unbroken graduation of colour in the photographic image into barely discernible waves of changing tone. The result is very beautiful. Like the photographic paper, the colour of the wool is saturated. The wool also absorbs light and does not reflect it. In consequence the tapestry almost has greater depth of colour than the original. One drawback, however, is that in the display the tapestry is lit so harshly that the yellow dominates and all the subtleties of the weaving are invisible unless you block out the light. Nevertheless it is superb. The remarkable way that this marriage of the contemporary with the medieval works invokes a sense of permanence and continuity which we don’t often find in contemporary art. A little bit like the persistence of watercolour, perhaps.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn contrast, Collected Shadows: the Archive of Modern Conflict at Stills displays too much of the myopic self-importance of the contemporary. It is a collection of 200 photographs, all drawn from a vast collection called the Archive of Modern Conflict. A few reflect their origin. There is a set of anonymous German snapshots of the Eastern Front, for instance. There are also aerial photos of bomb damage from both the Luftwaffe and the RAF. It seems typical of the loose way that this has all been assembled, however, that a German photo of Rotterdam airfield which is plainly labelled in the original is nevertheless wrongly identified, while an RAF photo of the breaching of the Mohne Dam is actually signed right on the breached dam by Guy Gibson, leader of the Dambusters raid, but this goes without comment. Most of what is on view seems to be completely random. There are pictures of the moon, of a solar eclipse, of buildings in India, people in various exotic costumes, almost anything in fact. Even if some of the images are fascinating there seems to be no apparent thread to link them. This is a Hayward travelling exhibition, so Stills is exonerated, but it is a frustrating experience all the same.

RSW until 8 March, Gary Fabian Miller until 7 May; Collected Shadows until 8 April