Art reviews: Navid Nuur | Toby Paterson

Navid Nuur Render-ender

Dundee Contemporary Arts

Star rating: * * *

Toby Paterson

Fife Contemporary Art and Craft @Kirkcaldy Galleries

Star rating: * * * *

In the short interpretative video that accompanies Navid Nuur’s exhibition at Dundee Contemporary Arts, he introduces himself: “I’m from the Netherlands,” he explains. “But the skin,” he says, playfully grabbing his cheek, “is from Iran.” It’s an arresting little explanation that says something not so much about the artist’s ethnic origin, as his distinctive way of approaching an issue. There’s something both instantly poetic and oddly mechanical about describing yourself in that way. And that’s both the pleasure and irksomeness of an exhibition, of some 30 individual art works, that includes each quality again and again.

Renderender has rendered the gallery spaces of Dundee Contemporary Arts from stern white cubes into rather cute little playgrounds full of apparently improvised and recycled stuff. Go in one door and you enter through green felt underlay and a beaded curtain. Exit through another and you leave through walls of what looks like that fancy foam sound insulation you get in top rank video installations but which turns out to be cardboard egg boxes. Between the two you’ll encounter polystyrene, empty matchboxes, artworks made from lemon juice or nail varnish, an upended wheelie bin and a pigsty. In some ways it’s easier just to list the stuff that makes his art works than to draw a line between them: this is the one made of a clothes dryer, pegs, Mylar and aluminium roof paint. Over here it’s the hot water bottle on the marble table over the mirror.

Advertisement

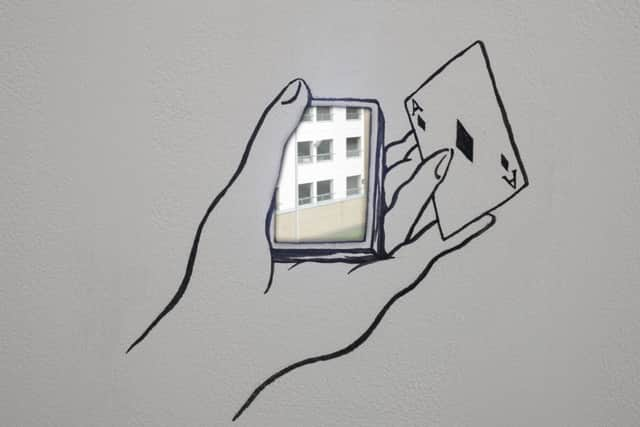

Hide AdNuur was a designer before he was an artist and in some ways his pieces show that – each involves an unusual process, a surprising material, a perceived problem to be solved, or a kind of trick in the creation, many of which might make you smile or nod in recognition. In gallery one, for example, the untitled work on the first wall is a series of weather maps of the prevailing conditions in Dundee during the installation of the show. The wall drawing has been made from ash, created by the striking of 5,000 boxes of matches. The empty boxes are strewn on the floor. On the adjacent wall is a drawing of a hand performing a card trick – the surprise is that one of the cards is created by cutting a card-shaped hole in the gallery wall, revealing that it is made of board and flashing a glimpse of the outside world through the concealed window beneath. Broken Concept is a series of ragged little polystyrene sculptures that turn out to be a grander scheme. The artist makes them according to a strict set of rules, but when the weak material can no longer bear the weight of his structure it snaps. It is these broken fragments he chooses to display.

Quite what weight Nuur’s work carries is the underlying problem for this show. In the darkness of the main gallery you find yourself clutching your visitor leaflet trying to read in the half light, because each work doesn’t speak directly but must be understood through explanation: the big blob that turns out to be a slide of the artist’s tear, the sculpture that is a three-dimensional model of an ink blot soaking through sheets of paper. There are flashes of insight, some sense that each work represents complex systems of physics or mechanics or representation. And a wonderful freedom with material: City Soil is a sculpture made by burning the excess waste materials in a giant wheelie bin, giving a sense that the work is circular in a positive way. Renderender is playful and delightful in both its energy and its representation of energy, but in the end it is a series of individual adventures rather than a coherent story, an attitude rather than a point of view.

In Kirkcaldy, Toby Paterson has just opened one of the first exhibitions of the Generation: 25 Years of Contemporary Art in Scotland project, the nationwide endeavour for this Commonwealth summer. I must declare an interest – not in this, or any of the more than 60 exhibitions that will take place from Stromness to Dumfries, I haven’t been involved in any of them – but I am currently editing two books on contemporary art in Scotland in the period that will be published in the summer under the Generation umbrella.

I make no secret of the fact that I think that Generation, which seeks in particular to give young people access to the mechanics and the mystics of the incredibly successful contemporary art scene in Scotland through exhibitions and projects in their own neighbourhoods, is a good idea. My life changed forever when an enthusiastic art teacher took me to see a tough and complex contemporary art exhibition when I was 17.

The proof of the pudding, though, will be in the individual shows and Paterson’s is a good start, a packed and coherent exhibition that along with paintings and prints uses Remnants, the series of sculptural elements he developed for a recent show at the Glasgow Print Studio gallery. Each sculpture, be it tall column, small cube or low wall, shows a building material, from brick to shuttered concrete, and thus the lovely but constrained parquet floored gallery is transformed from interior to exterior world, from civic elegance to city street.

Paterson’s work has long been an exploration of the concrete aesthetics that have once more come to the fore in recent debates about the final fate of Glasgow’s Red Road flats. What are we to make of the idealism and failure of post-war modernist architecture, what is good or bad about that built environment? How might we make the modern world a better place? In the past this has sometimes been evidenced by the Glasgow artist’s passionate attachment to the overlooked and the afflicted in our urban environments. These days it’s a kind of melancholy and an acute and poetic attention to detail.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn paintings on Perspex and aluminium, in new works and some welcome older ones showing church and hospital buildings, Paterson’s show is gentle and quite moving, transforming the unloved into the curiously lovely. A delicate new geometric screenprint, Tower, has a back to basics simplicity. Salt Corrosion is a singing new blue painting on aluminium inspired by the area around the car park on Kirkcaldy Esplanade. Young people from Fife College have worked on an interpretative video for the project and visited the artist in his studio. That art can be made, not always out of flights of fancy or New York high life, but out of grey days and grey concrete in Fife seems an essential and welcome reminder for any generation.

• Navid Nuur until 15 June. Toby Paterson until 22 June, and touring to Inverness, Dumfries and Peebles later this year