Art reviews: Louise Bourgeois, Edinburgh

Louise Bourgeois: A Woman Without Secrets

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh

* * * *

Louise Bourgeois: I Give Everything Away

The Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh

* * * *

As a child, Louise Bourgeois lived in Antony, a suburb of Paris on the banks of the River Bièvre. Her parents were in the business of tapestry restoration. The life of the artist, who by the time she died at the age of 98 in 2010 was understood as a towering figure of the 20th century, is now the stuff of legend.

We know she learned to draw to help in the family business: the extremities of tapestries were most likely to be damaged so she soon excelled in hands and feet. After studies at the Sorbonne, she trained under the painter Leger and moved to New York with her husband, the American art historian, Robert Goldwater, where she was surrounded by the exiles of a great European art scene.

Advertisement

Hide AdBourgeois was in her seventies when she was recognised as an artist of unique ferocity and personal insight. In an era that became known as the century of the self, her transformation of personal demons into monumental sculpture, her unusual and expressive materials such as old fabrics, wool and latex and her rigorous exploration of the contradictory and often masochistic lives of women all chimed with the age.

Her own story was true, but still somehow semi-fictionalised. Not because she was a liar but because she recognised the power of personal narratives both as healing and as intellectual fuel. There was her childhood discovery of her father’s affair with her English governess, which led to a lifelong rage, expressed in stitched sculptures of figures in anger and anguish. Then there was the double-edged evocation of her mother “neat and useful” as a spider, which found towering, intimidating expression in Maman, the giant arachnid sculpture that ushered in Tate Modern in 2000.

Viewing these two shows, the first a terse but well structured and representative sample of late works under the auspices of the Artist Rooms Collection, and the second a showing of Bourgeois’ Insomnia Drawings made in 1994-5, it is to the River Bièvre that one keeps returning. As the artist wrote in Ode to Bièvre, the 2007 cloth book on show at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, the river was important to the family business. The water was essential in washing the tapestries, it fed the family’s flourishing vegetable garden, but its tannin rich waters were also important for fixing dyes for the thread used in restoration. It is these contradictory impulses of movement, cleansing and flow, growth and nurture, fixing and restoration that drove Bourgeois’ mature work.

Thus the exhibition A Woman Without Secrets, moves register between formal sculptures in bronze and marble, fluid drawings, and the assemblages known as cells that formed her last body of major works. It shifts between big statements and provisional questions. Forms are either terribly fixed, like the haunting bronze Spiral Woman in which a female form is bound as though by a boa constrictor, or wide reaching and ambiguous, like the monumental drawing series Al’Infini.

There is a simple sternness to the layout of the SNGMA show, which makes it a sober yet rounded synopsis of her art. There are no great highs or set-pieces. The 1994 Spider, a metal monstrosity, carrying a ghostly pale marble egg in its sac, is room-sized but not overwhelming.

But where major recent shows of Bourgeois have often focused on her individuality, her dramas and her rages, there is an air of completeness and quietness to this selection of work that allows you to reflect on her career as a whole. This is a show about consistency and connections, the working and reworking of motifs. After Goldwater died, Bourgeois embroidered his old handkerchief, she used and re-used the material of her life to make sense of it.

Advertisement

Hide AdIf there is an emblematic work, it is the suspended sculpture, Couple, constructed from stuffed old clothes, that swings in the air currents in the gallery. It looks like two figures entwined. This work doesn’t seem to be some kind of triumphalist rendering of her marriage, but a recognition of the struggle to disentangle our own needs and motivations from those of others.

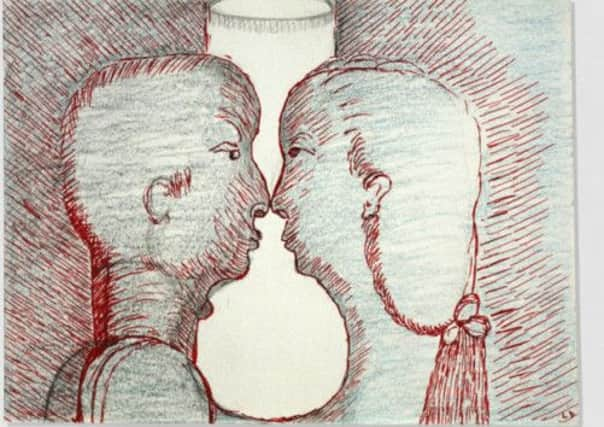

The Insomnia Drawings at the Fruitmarket Gallery in I Give Everything Away, were never originally intended for exhibition. The artist reached for her red biro and for scraps of lined paper or music manuscript to keep anxiety at bay, but these 220 works, representing months of sleepless nights, are neither vulnerable nor exposing. They document Bourgeois’ organising intelligence, her challenge to sleeplessness and doubt.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“The fear of fear will bring the fear”, she wrote in 1960. Awake in her house over a cold and wet winter in 1994, she made drawings to survive. She charted all the houses she had lived in, evoked gardens and feathery forms, the towering architecture of New York, buildings that are held up by muscled caryatids. Chaos always seems at hand. There are repeated images of rain and flooding. But when the artist appears nearly overwhelmed by rising tides, she restores order. The tidal rush is transformed into near images of uniform waves, flowers, neat squares, musical notation, clouds and circles, the ticking of the clock. Systems saved her from anxiety and being overwhelmed.

I’ve seen these works on a number of occasions, but they are usually installed as a dense and confrontational grid. At the Fruitmarket they are displayed in a single line around the walls, making you aware of the ticking circularity of the clock and the thread, or stream, of the artist’s life and work.

Late in life Bourgeois had a traumatic visit back to Antony. The river had disappeared, concreted over by town planners, pushed underground and out of sight. Bourgeois had learned over a long life that you couldn’t suppress a flood of feelings like that.

In her last works, she takes leave of us. In fierce etchings of throbbing red intensity she made images that might be flowers or ovaries, trees or spinal columns. There are words scrawled in pencil, “I am packing my bags, I leave the nest, I leave my home”.

These are works about her own departure, her final withdrawal, but for all their wild expression her art remains ordered to the last: “I distance myself from myself,” she wrote. “I give everything away.” In these final works the pulsing of her life’s blood runs through her like a river that is always contradictory: mirroring and mending, flowing and fixing.

A Woman Without Secrets until 18 May 2014; I Give Everything Away until 23 February 2014