Art reviews: Discordia | Lucy Skaer

Discordia

Patricia Fleming Projects, Glasgow

Star rating: * * *

Lucy Skaer: Leonora

Hunterian Art Gallery, Glasgow

Star rating@ * * * *

Moyna Flannigan: Stare

Star rating: * * * *

Nathan Coley: The Lamp of Sacrifice 2004

Star rating: * * * *

GoMA, Glasgow

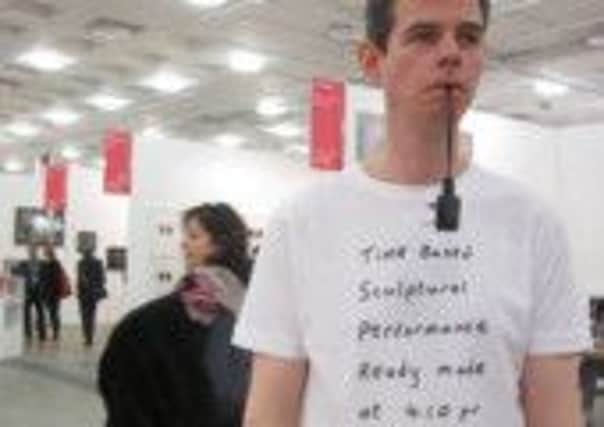

In a city whose art community is still reeling in the aftermath of the Glasgow School of Art fire I was much cheered by the energy of Discordia, a mixture of new and archive T-shirts designed by artists and hung in South Block artists’ studios by Patricia Fleming Projects. Here you can see history unfold, from a 23 year-old tee that marked Windfall, the 1991 exhibition that is often heralded as a breakthrough moment for art in Glasgow (yes, if you must know, it has the stubborn neck-grime to prove it) to new works by artists including Sue Tompkins, David Sherry and Scott Myles. I liked Christine Borland’s image of an ominous and scarred baseball bat, Kevin Hutcheson’s cruel appropriation of the Kappa sportswear’s notoriously louche logo and Ross Sinclair’s appeal for “free electric guitars for teenagers” – a mild suggestion compared to one of his T-shirts which, back in the mid-nineties, brought policemen unfamiliar with the popular music of the era to the door of a prominent art gallery. T-shirts are lo-fi: a simple and reproducible way of making art or communicating ideas.

A digital file can be printed up quickly and inexpensively. Like all the shows I am reviewing this week the show is part of the Generation programme and artists’ T-shirts have their own tiny little lineage in a much larger history of DIY culture. The new limited edition designs for Discordia are available to buy at £25 a pop. Lest we get entirely carried away with nostalgia, Torsten Lauschmann’s satirical work, an image of a rampaging, flesh-eating zombie beneath the words Glasgow Miracle, suggest that it’s time that much of the mythology around the city’s art scene is finally laid to rest. I’m very much hoping that those of us who make a living from such cultural soundbites and media simplifications might be forced to wear them as a fitting punishment.

Advertisement

Hide AdYet all artworks are, to some extent, like zombies: undead and untethered, neither living nor entirely inanimate. Once released by their makers they might come crawling out of the woodwork or at least out of storage without due notice. If Generation is to achieve its aim, it needs to convince us that recent art works have historical weight and sustained life. It’s that curious equilibrium that is such a key part of Lucy Skaer’s installation Leonora at the Hunterian Art Gallery. Leonora has its roots in a visit that the artist made to Mexico City in 2006. She was living and working in New York and had heard that the British surrealist painter Leonora Carrington, who was born in 1917, was still alive and living across the border in Mexico. Armed with a scrap of paper and a scribbled address she sought out the artist.

Skaer’s brief film, presented with whirring projector on show in the gallery, is a mute portrait of the older artist. Her hands riven with veins and placed firmly upon a table top, we see her simple surroundings and a row of plastic clothes pegs on a line. What does it mean, this image of the artist? How do we encounter the weight of history? Is this a chilly warning about our own futures, about the relentless movement from the present to past tense? But Skaer’s work is ambiguous, and she uses the encounter for her own ends, telling us less about Leonora than her own relentless pursuit of ideas and questions.

On the wall as part of the installation, which is largely drawn from a series of works in the Hunterian’s own collection, is one of Skaer’s “black drawings” a series of works made around 2007 in which her method of using black swirls of marker pen and crude pencil marks is both notably labour-intensive and deeply confusing. Peering through the darkness you gradually make out the image of a whale skeleton. The living is now the dead, the legible rendered illegible. You can’t recall the point in which the whale coalesced before your eyes. Are images reliable or unstable? Carrington died in 2011. We must now think through whether she lives on through her own work, through words or through her moving image, endlessly looping on celluloid in the gallery.

Not quite crawling out of the woodwork but emerging from storage at the National Galleries of Scotland and now on show at GoMA is Nathan Coley’s work The Lamp of Sacrifice 2004. Commissioned 10 years ago for a solo show at the Fruitmarket Gallery, it rests on the Victorian critic Ruskin’s assertion that there was a crucial distinction between buildings and architecture. What happens to bricks and mortar, poured concrete or fine Scottish sandstone when it is stripped of its symbolic context?

A decade ago Coley opened the Edinburgh Yellow Pages and listed all the places of worship each church, mosque and temple wedged in between a list of pizza deliveries and planning consultants. Every building was recorded and rendered anonymously in brown cardboard: a miniature village. For a work that is so clinical in many ways, it is still surprisingly physical. It took four months of slog with Stanley knives wielded by Coley and his assistant. There was a time when you couldn’t meet him without noticing the scratches and I remember the delicious irony about some of Edinburgh’s most distinctive architecture, including St Giles Cathedral, being reconstructed in corrugated cardboard in a light industrial unit in Dundee. The Lamp of Sacrifice has survived the intervening ten years remarkably robustly, the pencil lines still deliberately visible, the sharp edges still striking. Lit from above under natural light it looks more handsome than in any previous presentation I’ve seen.

Downstairs in the gallery the zombies are perhaps more literal, for there is more than a little of the walking dead in Moyna Flannigan’s marvellous, monstrous women in Stare, a group of new paintings that still smelled delightfully recent at the opening. Flannigan dwells on the expulsion of Adam and Eve, and of the perceived sins of women ever since. Revelling in the outsider status of both women and her chosen art form, her women are scarlet-lipped, open-legged, craven and disreputable, her paint swift and lurid in blue-blacks, orange and greens. Three giant Eves process like teetering statues of liberty, babies are abandoned by fearsome spider-women, skeletons left scattered in their wake. Part mother courage, part Lady Gaga these women simply will not rest.

• Discordia until 4 July, Lucy Skaer until 4 January 2015; Nathan Coley until 1 March 2015; Moyna Flannigan until 2 November