Art reviews: Allan Ramsay - Edinburgh and Glasgow

ALLAN Ramsay: Portraits of the Enlighten-

Ment

Hunterian Art Gallery, Glasgow

Rating: * * * *

ALLAN RAMSAY AT 300

National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh

Rating: * * *

Compared to the ballsy, blowsy art of Sir Joshua Reynolds, there is a kind of cool distance to a Ramsay portrait. Nicholas Penny, director of London’s National Gallery, has said that he makes us “aware of the space between us and [his sitters] and of the air about them”.

And yet it’s in this gap that you begin to realise there is an “us and them,” and that a portrait is something more than an image. His subjects were real people in a room. They were looked at by him, were appraised by him. They similarly appraised the Edinburgh man with a prominent jaw and some aptitude who somehow became exceptional.

Advertisement

Hide AdAnd there’s his career: it’s hard to fathom an artist who was so prominent and yet often talked about as though virtually invisible. His astonishing early public reputation was eclipsed by the raging debates about art between figures like Reynolds and Gainsborough and an art history that told other stories about his lifetime.

There’s a popular perception that at the height of his fame he somehow withdrew, when the truth is by 1767, when he became Principal Painter in Ordinary to King George III, he was so successful he could do what he damn well pleased. That meant churning out the royal portraits by the hundred, but he no longer needed to rely on the aristocratic patrons who made his name.

I often like to think of him in London, where he trained and later lived, as he clambered his way through posh drawing rooms and from studio to studio as that canny stereotype of the ambitious Scot. Like Alasdair Gray’s character, Kelvin Walker, he is another Scotsman on the make.

He was as dependent as any of his fellows on a tight-knit cabal of Scots in London, the Scotia Nostra of their day. When their luck ran out, when John Stuart, Earl of Bute fell from Royal favour after his short-lived run as Prime Minster, it is well to remember that Ramsay reconstructed the image of his Scottish friend and confidant, the philosopher David Hume, to make him a Brit.

The particular joy of the Glasgow show, which is small and measured, and not royal at all, is the focus on real friendships, relationships and intellectual portraits. The display reminds us of the tightness of the artist’s studio, the intimacy of the dinner table. The highlight is in its exploration of Ramsay’s female portraiture. Clever women saw a man who was unafraid of their abilities and prepared to portray them honestly. But we should be clear of the nature of the transaction: as sure as Ramsay made their likenesses, these women – smart, rich and well connected – made him, not the other way round.

The best is Frances Boscawen, the original bluestocking, famously, self-mockingly “unacquainted with beauty”. She is young, yet perceptive and she looks out of the picture unadorned and unafraid.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn Edinburgh, a small display of drawings at the National Gallery of Scotland exposes both Ramsay’s nascent talent and the workaday clunkiness that he strove hard to overcome. His earliest pictures might be those of any able teenager. But in his earnest sketchbooks, completed at the short-lived Academy of St Luke’s, wonderful copies of exotic animals like camels and lions show the sheer grit that would get him where he wanted to be.

It is the small studies that are most captivating: the beautifully rendered hand of his second wife, Margaret, holding a flower that she will put in a vase. Ramsay’s notable obsession with hands is an obsession with graft and doing, with making and manufacture. Like a manifesto for the Enlightenment his best portraits are all hand and eye.

Advertisement

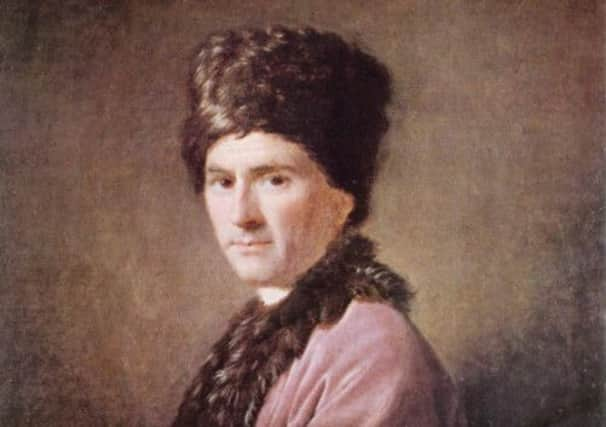

Hide AdSadly, at the heart of the Hunterian show is a lack. Whilst the gallery has obtained a loan from the Scottish National Gallery of Ramsay’s extraordinary 1766 portrait of the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, it hasn’t got his 1766 picture of David Hume.

These two portraits, made in one turbulent year, are amongst the best stories in the history of art and philosophy. Rousseau, cast out of Switzerland and unwelcome in France, makes his way with Hume’s protection from Paris to England. At first the philosophers are firm friends and with Ramsay a plan is hatched to paint the Genevan’s portrait. Ramsay will make it and gift it to Hume. And what a picture it is. Rousseau in his Armenian robe and hat, a curious costume first designed to disguise an ever-present catheter, but soon associated with the philosopher’s ideas on the primitive and nature.

But of course there is a catch. Ramsay’s studio assistant will make a copy and everyone knows it will make money and generate publicity. Rousseau had lots of reasons to feel paranoid that year and soon he begins to express his discomfort. It blows up into a full public row.

The catalogue must airily dismiss the whole debacle as simply too well known to rehearse again. But blimey, do take look at that portrait: Rousseau, his hand on his heart, has a furrowed brow, hesitancy in the eyes. He is caught in a light that is not just the blaze of the brilliant Enlightenment, but also the spotlight of paranoia.

Perhaps to view the Hunterian show is to see a moment when what an artist could be or do was changing, A figure like Reynolds was all about trying to put painting on a firm public footing, with its own institutions, language and literature. Ramsay was all about personal transactions and the status of the artist himself.

His social mobility was not accidental. His clever dad, the poet Allan Ramsay, and the great men of the Edinburgh Enlightenment, helped construct it. But for the trick to work one must never draw attention to it. Ramsay’s rise to fame must seem like it is case of natural genius and hard work, not a squalid scrabbling for royal favours or pensions.

Advertisement

Hide AdHe was an artist who gained the trust of his patrons sufficiently to look them in the eye as if they were equals and thus, for one of the first times in portraiture, let them truly look back at us.

• Allan Ramsay: Portraits of the Enlightenment runs until 5 January; Allan Ramsay at 300 runs until 9 February

Moira Jeffrey