Art review: William Blake: Apprentice & Master

WILLIAM BLAKE: APPRENTICE & MASTER

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

*****

If there was any lingering suspicion that such opinions may have had some foundation in fact, a major exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford sets out to put the record straight once and for all. It is a brilliant assembly of Blake’s art and that of his immediate followers, but it also tells the story of his life from his early years starting drawing school at the age of ten to his end, impoverished, but surrounded by devoted admirers. Like Turner, and indeed Hogarth, in an acutely class conscious society, Blake came from what was regarded as the lower ranks. Turner’s father was a barber, Blake’s a hosier. It is greatly to the credit of the parents of both artists, but also testimony to the opportunities available and the value put upon the visual arts at the time, that they were able to train. Thereafter too, if Blake did not grow rich as Turner did, at least he was able to develop his art with a high degree of real independence.

At 14 Blake began an apprenticeship to the engraver, James Basire, who counted the Society of Antiquaries among his clients. The exhibition not only shows the kind of work Blake did with Basire; work commissioned by the Antiquaries gave his young apprentice the opportunity to spend many formative hours studying the art of the Middle Ages in Westminster Abbey, for instance. The exhibition also explores the stimuli he found in London more widely. As a boy he frequented print sales, studying what he saw in diverse lots of unmounted prints. He learned to prefer the austere, linear style of the earliest print makers like Dürer or Mantegna to which he always remained loyal, rather than the chiaroscuro of Rembrandt. After seven years as an apprentice, by then able to keep himself, he went to the Royal Academy schools where he was taught by artists like Henry Fuseli and James Barry, but also by the Scottish anatomist William Hunter. From Hunter, friend of Hume and Ramsay, Michael Phillips suggests in the excellent catalogue, Blake learnt to value precision and minuteness in striking contrast to the “general ideas” advocated by the Academy’s president Sir Joshua Reynolds, whose art and theories he heartily detested as vague and imprecise.

Advertisement

Hide AdThrough his commercial work Blake became a successful and respected member of the artistic community. If later he lived in relative poverty, this was certainly partly because he was ahead of his time, but he was also a political radical and didn’t hide it. Indeed he gave his views full, if often rather cryptic expression in his art. Turner, also a radical, was more careful. He was also younger. Blake’s career began against the background of the French Revolution and then as now, the government took the opportunity of an external threat to limit personal freedom. Indeed, in a bizarre episode during a sojourn in rural Sussex, the only time he spent away from London, he was charged with sedition after an argument with a soldier who trespassed in his garden. He was acquitted, but suspected that the charge was political and it seems he may well have been right. This climate of repression eventually drastically curtailed his opportunities

CONNECT WITH THE SCOTSMAN

• Subscribe to our daily newsletter (requires registration) and get the latest news, sport and business headlines delivered to your inbox every morning

Blake’s small, neat printing room in the house in Lambeth where he lived during the most prosperous period of his life has been recreated from plans and contemporary accounts. On the wall hung two of his own largest engravings and Dürer’s great print Melancholia, which he may have bought when he haunted the auction houses as a boy. Here and throughout the exhibition we get a vivid sense of a man who was not always an outsider, but made his way professionally, enjoyed the admiration of his peers and derived enough support from them to pursue his wonderful art. If he had had more opportunity he would certainly have worked on a bigger scale. His largest surviving picture, Chaucer’s Canterbury Pilgrims – a treasure of Pollock House – is just five feet across. He did exhibit at least one much bigger picture in his only one man exhibition, but it does not survive. He detested oil paint, however, and the smaller scale dictated by working on paper certainly suited his genius. The show includes prints in various forms, mostly coloured either in the printing or by hand, together with drawings and watercolours.

The illuminated books were the most remarkable of his productions and are truly beautiful. The Songs of Innocence was one of the first, later paired with the Songs of Experience. The former is a wonderful evocation of the innocent vision of a child, the second a devastating excoriation of the corrupt reality of the adult world. There followed the prophetic books including Europe, America, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell and Jerusalem, in which he developed his philosophy of the supremacy of the imagination and its struggle with the structures of religion and politics that we erect and which control and distort it. Europe includes one of his grandest images, The Ancient of Days, the figure of God measuring out the universe with a pair of compasses. The opening plate to Jerusalem, his longest and most ambitious book, shows a man with a lantern entering a dark doorway. Blake’s young admirers called him the Illuminator, so perhaps obliquely it is a self-portrait. (The hymn Jerusalem, much loved anthem of the Last Night of the Proms, comes from his book Milton.)

Being a printmaker was integral to everything Blake did. Medieval manuscripts, seen as belonging to a purer, less corrupted age, were the model for his illuminated books, but these ancient books were laborious to produce and each was unique. Blake, however, devised an ingenious method that allowed him to print text and image in a single plate and so produce his illuminated books in multiples. The development of this technique is explored in detail, but it also had a metaphorical value to him as a practical expression of the unity of word and image. Like Hogarth before him, also an engraver and certainly his role model, Blake saw that engraving, as a form of publication, offered the artist a way of reaching a public far beyond the confines of wealth and good taste. That was the ambition behind the illuminated books, however limited their numbers were in practice. Hogarth too regularly added text to his plates, however, and even composed a poetic narrative for his Marriage à-la-Mode so the claim made here that Blake’s combination of word and image was unique has to be qualified.

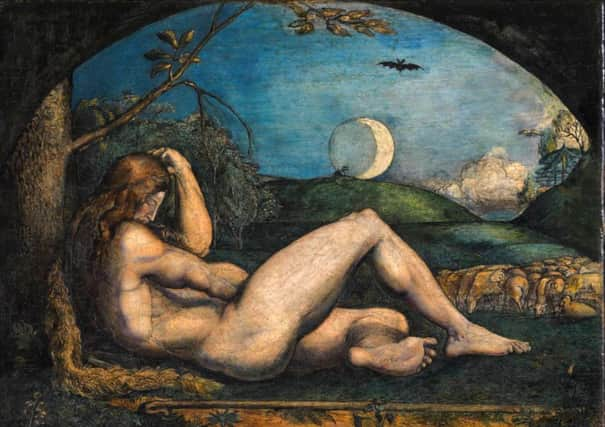

Some of Blake’s grandest designs have no words associated with them, however. These are the large, coloured monotypes – a process that he devised – that he made in his Lambeth studio. They include the memorable figures of Newton and of Nebuchadnezzar, but perhaps best of all is Pity, the marvellous illustration to Macbeth’s invocation of “pity, like a naked newborn babe” blown upon the wind. In the last years of his life Blake also embarked upon a series of large, watercolour illustrations to Dante. Many of these are in fact wonderful landscapes. We don’t usually associate him with landscape, but it was these pictures together with a group of tiny and intensely poetic landscapes made for an edition of Virgil that were the principal inspiration for the young painters who gathered round him in his final years. They called themselves the Ancients and a selection of their work closes the show. Samuel Palmer is the best known of them. His magical landscapes directly inspired by Blake are a fitting tribute to one of our greatest artists.

• Until 1 March

SCOTSMAN TABLET AND IPHONE APPS