Art review: Vija Celmins, North Uist

Vija Celmins: Artist Rooms

Taigh Chearsabhagh, Lochmaddy,

North Uist

Star rating: * * * *

Sometimes, during my visit to North Uist, it feels as if I am on water more than land. Arriving on neighbouring Benbecula on the Loganair flight from Glasgow feels like landing on a rare solid spot in a fractured set of skerries. The taxi ride to Lochmaddy is leisurely: my charming driver is in his eighties and appears to be a zen master when it comes to roadcraft, so there is plenty of time to look out of the window. The boundaries one might expect from an island are endlessly blurred: low slung and fragmented, North Uist barely reaches above sea level in parts. Where the land ends and sea or loch begins starts to feel like a moot point.

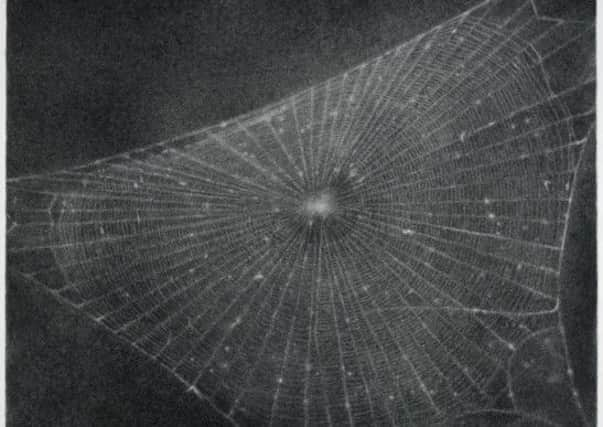

It’s hard to think of a more perfect place, then, to see the work of the Latvian-born American artist Vija Celmins, for the lack of a defined perspective or a secure set of boundaries is more than a hallmark of her work – it’s the heart of the matter in everything that she does. When Celmins draws the night sky, a choppy sea or the rough pockmarked surface of the desert, she does so with a distinctively neutral eye. All the things that make the visible word legible – the human perspective, orientation, habitation – disappear. When Celmins draws water, her drawing is all water, when she draws stars you are among them. A spider’s web might as well be a whole universe.

Advertisement

Hide AdCelmins is showing at Taigh Chearsabhagh, which itself is a centre of the universe in this bit of the world. As well as a small gallery, it hosts a shop, a decent café and a centre of education that offers both National Certificate and BA degree level courses in art, in partnership with Lews Castle College and the University of the Highlands and Islands. The arts centre boasts one of the best gallery views I’ve ever come across, as well as artist studios and digital media facilities under the development project UistFilm.

The Celmins show is part of Artist Rooms, the initiative set up by Tate and the National Galleries of Scotland when they jointly acquired the art dealer Anthony d’Offay’s collection in 2008. If Artist Rooms was the shot in the arm that the country’s public collections needed, when hopelessly outbid on the international art market, then Artist Rooms on Tour, supported by the Art Fund and, in this case, Creative Scotland is the mobile clinic. If public money is to be spent on our collections then it must mean the whole public: north, south, east and west. And national collections must truly understand themselves as national, as important in Dunoon as Dundee, in Lerwick as well as London.

This is the first time Artist Rooms has visited the Uists. The Celmins show also marks another important collaboration. It is part of Broadreach, an initiative that sees Skye’s redoubtable Atlas Arts curate a visual arts programme in the gallery and work with the wider community in the Uists.

The director of Atlas is Emma Nicholson, who with high-level education experience at the National Galleries of Scotland and the Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney, as well as roots in Skye, was a natural for the job. Atlas has an office in Portree but it doesn’t have an expensive building to maintain; instead it works with what’s out there, and with artists like Alec Finlay, Walker & Bromwich and Ilana Halperin it has done so well. At Taigh Chearsabhagh, Atlas can apply its hard-won knowledge in the communities it serves with the advantages of its expertise, a firm base and local knowledge. The project has also seen a new curator, Gayle Meikle, take up post.

All of this, however, will only be box-ticking if the work is no good. As a statement of intent Artist Rooms and Celmins is an intriguing and apposite choice. On the Artist Rooms roster she is in some ways the sleeper, without the imprimatur of Andy Warhol, the in-your-face fame of Robert Mapplethorpe. There is a slightly embarrassing interpretative film that goes with the show in which Anthony d’Offay explains that there is a ten-year waiting list to purchase her work, as though rarity or expense was measure of value – that’s the dealer in him unable to let go.

But the truth is that Celmins’ work is desirable because of its skill and discipline and importance in post-war art history. Celmins’ early work was a product of her disorientated roots: a wartime childhood in Latvia, a family flight to East Germany and on to Indianapolis at the age of ten in 1948. One of her most famous images, Suspended Plane, in San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art, is a painting based on a photograph of a B26 bomber. It is as though in that stilled moment she might stop the perpetual motion that had uprooted a continent and continued to disrupt the globe. The painting was made in 1966 during the Vietnam War.

Advertisement

Hide AdOn North Uist the focus is on the night skies and the sea. Celmins’ charcoal drawings, woodcuts, etchings and mezzotints appear mute at first, but they are compelling. In a simple room hung with 11 works you can see the way Celmins applies herself again and again to the simplest tasks and that out of this discipline she builds images of staggering complexity. She pictures the surface of one of Jupiter’s moons, the arc of light of shooting stars, the universe in reverse: dark matter where there should be pinpricks of light. Deliberately working from photographs, her art ran counter to the emotional volubility and machismo of abstract expressionism, whose reign in American art she quietly helped usurp.

For someone from the mainland visiting North Uist it is hard not to fall into clichés about island life. During my trip I meet the artist Sophie Morrish, who came to North Uist to teach and is now pursuing her art full time. Sophie has three dogs, but in recent days she has also acquired a lamb that has been rejected and abandoned by its mother. I meet the journalist Iain Morrison from South Uist, at the opening night. I stay up late looking at the stars, while he watches the clock: he is also a crofter, it’s lambing time, and he expects a 5am start. The island is, of course, also hugely cosmopolitan. The ferry terminal at Lochmaddy means that the settlement is a crossing point for this corner of the Hebrides. Taigh Chearsabhagh gets thousands of visitors a year. Among them, this month, has been Celmins herself. Every school across the Uists and Barra will see the show.

Advertisement

Hide AdIt’s time for me to go. On a beautiful and brisk spring day the water is choppy but sparkling, and everywhere there are birds on the move. Skeins of geese pass overhead, there are Hooper swans stiff-necked and ancient-looking where the mute swan is all artfulness and arch. I see two hen harriers hanging low over rough, wet turf, almost static. It is as though they are suspended mid-flight and I realise I am seeing the world through Celmins’s eyes.

• Vija Celmins: Artist Rooms until 28 June, www.taigh-chearsabhagh.org