Art review: Stands Scotland Where She Did? Timothy Neat at 70

This article contains affiliate links. We may earn a small commission on items purchased through this article, but that does not affect our editorial judgement.

Stands Scotland Where She Did? Timothy Neat at 70

Peacock Visual Arts, Aberdeen

Star rating: * * * *

The paper was the Dundee Courier. The occasion was Timothy Neat’s 1989 triumph at the Barcelona Film Festival for Play Me Something which Neat directed and co-wrote with the eminent writer and critic, John Berger. Berger also makes an appearance in the film, which is an adaptation of one of his short stories. His co-stars are Tilda Swinton, Hamish Henderson and Liz Lochhead.

It’s good sport, of course, to poke fun at what looks like newspaper parochialism, but the intensely local and the passionately international seem essential to understanding Neat, whose 70th birthday is marked with Stands Scotland Where She Did? a major exhibition at Peacock Visual Arts in Aberdeen and the publication by Polygon of These Faces, a book of his photographs and drawings.

Advertisement

Hide AdA Cornishman who had trained at art school in Leeds, Neat found himself teaching in Lendrick Muir school in Perthshire in the late 1960s and at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art in Dundee through the 1970s and 1980s. As a writer, film-maker and photographer, his eye was trained on both the universal and the particular. But it was on Scotland’s nomadic traditions and its supposedly marginal people that it rested the longest. In Neat’s work the travelling people of Scotland such as the Stewart family and the singers, story-tellers and crofters of the Highlands become central, the standard-bearers of language and culture. In his film and photographs they are close to the earth and the seasons but neither simple nor without meaningful history.

Stands Scotland Where She Did? can’t begin to represent all of this, but in two large rooms it tries. The first looks at Neat as an artist and begins with a trip that he took, as a 19 year-old, to rural Spain. His photographs are not the most technically accomplished, nor the most systematic. However, his eye for human interest, for the rhythms of rural life in the streets of Andalucia and his sympathy for the continuity of ordinary human endeavour are touching.

There is something a little indulgent but disarmingly charming about the self-taught ceramics he is also showing. Most are practical vessels, some gently askew. The urge to make and to do provides a counter to Neat’s intellectual life, but also a manifesto, that making is a form of thinking itself.

In a glass vitrine are copies of Seer, the Dundee art magazine that Neat helped shape. They are a reminder of the contested political climate of the late 1970s and early 1980s, with red graphics and bitter editorials against the “shopkeeper mentality”. Here we can read the battle lines of radical Scotland versus Thatcherism; and that radicalism is writ large in a suite of new screenprints, A Baker’s Dozen: Twelve Stations of the Cross of Scotland. These are bold, graphic texts railing again injustice, with messages on everything from eco-politics to the Naked Rambler. Scotland is seen as “post war, post-industrial, post imperial”. And there’s an answer to the question posed by the exhibition title, stands Scotland where she did and free? – “no and yes.”

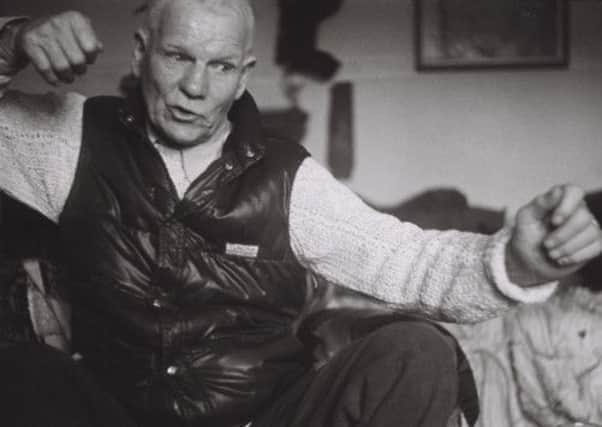

For many visitors it is the second room, a wonderful selection of archive materials and important photographs, that will excite. Neat’s relationships with figures like Berger, Henderson and Hugh McDiarmid is set down in portraits, scrawled correspondence, plans for monuments and memorials. The real glories, however, are his photos: the astonishing weatherbeaten face of Scots traveller Martha Mackenzie, pictured at Fortingall almost 40 years ago or Argyll traveller Duncan Williamson arms akimbo singing the ballad Jock o’ Monymusk in 1998.

Reading this complex chain of friendships, influences, and intellectual inheritance obviously begs questions of where Neat’s current influence might lie. Neat seems very much a product of his generation: he studied in the 1960s, but was able to reach out both to older peers and to his young students. But this exhibition is also timely because his work is gathering currency again amongst a new generation of artists, writers and musicians. The Scots-trained artist Ruth Ewan’s exhibition, Brank and Heckle, at Dundee Contemporary Arts in 2011 acknowledged its debt to Neat and to the shocking images of the singer Jean Redpath wearing a metal brank, or witches bridle, that featured in his film on Robert Burns, The Tree of Liberty. And I recently watched his wonderfully lyrical film about Scotland’s pearlfishers and travelling people, The Summer Walkers, in the company of a new generation of artists at Helmsdale.

Advertisement

Hide AdNeat himself is still making and doing. In his notebooks a gentle, pastoral ink drawing of beehives sits beside furious scribbled text on the war in Afghanistan. It’s the minute texture of lived life set against the desire for big ideas and big changes: the particular and the universal.

• Stands Scotland Where She Did: Timothy Neat at 70 is at Peacock Visual Arts, Aberdeen until 9 November, www.peacockvisualarts.com. These Faces is published by Polygon. Neat’s films will screen at the Belmont Picture House, Aberdeen, on 13 and 27 October