Art review: Scottish Design Galleries & Ocean Liners - Speed and Style, V&A Dundee

The new V&A Dundee is a signature building, and in projects such as this aesthetic considerations usually trump function (and cost). After all, whatever a signature building looks like, the one thing it should not look like is an ordinary building. The comparison with Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Bilbao is explicit. It is meant to work the same magic and bring thousands of visitors. Dundee needs them. It already has an annual funding gap. But Gehry’s building is shiny and conspicuous. This one is grey. It is handsome certainly, but it makes no impact from a distance in the haphazard jumble of Dundee’s waterfront.

Architect Kengo Kuma’s buiding is a composition which consists of two irregular chunks. There are no visible walls. The whole building is hung with a screen of horizontal concrete beams. Nor are there any verticals or even right angles as the sides twist and slope and bend back on themselves. One sharp corner overhangs the sea like the prow of a half-launched ship. The two blocks join across a gap like a sea arch with a view to water beyond. This sparkled the day I was there, but it’ll be grey sea and grey building much of the time. The architect has said his inspiration was the cliffs of north-east Scotland. You can see the analogy. So will the seabirds. The ledges are angled downwards and there’s also a bird scaring system, but there are miles of ledges and the birds will find a way sooner or later. A colony of kittiwakes or fulmars would add a nice dimension to the Scottish theme.

Scottish Design Galleries, V&A Dundee *****

Ocean Liners: Speed and Style, V&A Dundee *****

Advertisement

Hide AdInside, the best space is not museum at all: it is the double height entrance hall with shop, cafe and ticket desk. The concrete ledges outside are echoed here in sloping layers of wood, like flaps on an aeroplane. Another maintenance nightmare. Apparently you can only reach the first four layers with a hoover and they go the whole way up.

This space flows into the first floor via a wide, shallow black marble stair. Windows offer views to the Tay beyond and this luminous space over two linked floors is the most impressive feature of the whole building. Nevertheless it could be an airport or a bank. It is anonymous. There are no lead objects to say “Design Museum” or even “Dundee.” On the upper floor, a deconstructed car shows design from model to finished automobile: even a sophisticated machine involves hands-on artwork. Yet, looking like one of those shiny airport raffle cars that no one ever wins, it compounds the airport effect. There is a big commissioned work by Clare Phillips on the wall here, but its isolation in this huge space, quite wrongly no doubt, suggests commercial tokenism rather than aesthetic commitment.

There is a restaurant on this floor. A small open exhibition area is the first thing to suggest we are in a museum. The show here is of the diverse outcomes of a collaborative design exercise by students from around Scotland. The two main suites of galleries open from this upper space. The first houses the permanent exhibition of 500 years of Scottish design. The second is a massive temporary exhibition space currently showing Ocean Liners. This is a V&A show, but that is coincidental. The museum will take exhibitions from wherever and also originate them. It is the partnership in the design history display that gives the museum its V&A handle. The parent museum has identified some 12,000 items of Scottish interest in its vast holdings. Few have ever been shown and none in a way in which their Scottish origin is really signified. From early on, the new museum’s director, Philip Long, focused his ambition on this great, untold story, and a good many of the objects on show do indeed come from the V&A, although others are also from collections all over Scotland.

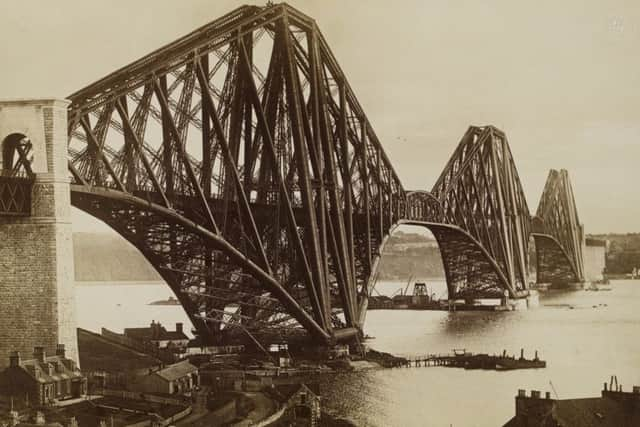

The story of Scottish design is far too diverse to follow a simple narrative and the display is limited to a manageable 300 objects. Grouped thematically, it manages to be remarkably comprehensive nonetheless. Certainly the received wisdom meekly accepted for too long – that Scottish design is clunky and provincial – must now be banished forever. A 16th-century silver baptismal dish by David Gilbert of Perth is both elegant and sophisticated. From the beginning, too, the story is international, not provincial. A chimney piece and mirror overmantel designed by Robert Adam reflects a high point in European design. Adam learnt his skills in Scotland, his style from the Antique in Italy and practised in England. Beginning with a bridge in St Petersburg, Scottish cast-iron buildings and the skills that went with them were exported worldwide. A picture of the magnificent suspension bridge that he built over the Menai Strait represents Thomas Telford, the Colossus of Roads, father of civil engineering and the first since the Romans to rebuild much of Britain’s infrastructure. Fittingly, too, the tragic first Tay Bridge gets a mention, as does the triumphant structure of the Forth Bridge inspired by its tragedy. Scotland was a leader in shipbuilding, as we see here from ship models and other things, but also in fashion. Paisley shawls were a must-have worldwide for much of the later 19th century. Since then tweed has established a similarly global market. Nairn’s linoleum from Kirkcaldy ably (and literally) backed by the Dundee jute industry covered the world’s floors.

Individual artists and designers stand out too. Phoebe Traquair, creator of some of the most exquisite objects of the Art and Crafts movement, and Sir Robert Lorimer, one of its greatest architects and designers, both get space. So does Patrick Geddes, the pioneering biologist, philanthropist and urban planner. Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s restored Oak Room is a centrepiece.

In the later 20th century Eduardo Paolozzi was an artist with international standing. An intriguing crossover object here is an elephant-shaped catalogue box that he designed for Nairn’s Linoleum. As well as Paisley shawls, there are other fashion designs and materials past and present. There is even an implicit interface between design and politics in John Byrne’s stage set for the travelling production of The Cheviot, the Stag and the Black Black Oil. Dundee’s own DC Thomson, creator of the nation’s favourite comics, is represented by drawings for Dennis the Menace. It is a shame though that neither the Broons nor Oor Wullie get a mention in this definitive Scottish show. There is beautiful early porcelain, but neither Scottish sponge ware nor Wemyss ware, but these are tiny omissions. There is so much more and it is a terrific story well told. (It is also backed by a book, The Story of Scottish Design, edited by Philip Long and Joanna Norman.) The whole enterprise is a memorable achievement.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe Clyde was the birthplace of some of the greatest liners and so Ocean Liners in the temporary galleries follows on easily from Scottish design. This too is stunning. The great liners that before the Second War raced across the Atlantic – 80,000 tons at nearly 40 miles an hour – were masterpieces of marine engineering, but also of design at is most extravagant and luxurious. You get a real sense of the first from the ship models and film and photos of the ships being designed and built. The second is vividly brought home by furnishings and art works, a life size mock-up of a swimming pool, complete with elegant swimmers, and by film and indeed actual costumes worn by very rich passengers out to impress. All that glamour led inevitably to on-board romance, not something you could illustrate perhaps, but in fact JD Fergusson’s painting L’Americaine makes very clear exactly what went on. Shame it’s not in the show. Overall though, the exhibition does record brilliantly a lifestyle as lavish as any lived by the ancient Romans, but one which flourished for barely the span of a single life.

Ocean Liners until 24 February