Art review: Mixed messages on Scottish independence

The Shock of Victory

CCA, Glasgow

Rating: ***

Document Scotland: The Ties That Bind

Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh

Rating: ****

Thirty six years ago, when the first referendum on Scottish devolution failed, wrecked by a Labour amendment, it seemed to focus minds. Frustrated politically, we gathered our cultural energy to prove who we were. A few straws in this new wind, for instance, were Steven Campbell’s degree show in 1982, the publication of Lanark in 1983, or the founding of the Scottish Poetry Library in the same year. In my own more modest case, it determined me to write the history of Scottish art. A flight from tartan and heather, the need was to put our cultural identity on a modern footing.

If, after the more dramatic events of 2014, two exhibitions, The Shock of Victory at CCA in Glasgow, and Document Scotland: the Ties that Bind, photographs at the Portrait Gallery, are again straws in a post-referendum wind, they suggest this time our reaction is less certain. They are in fact really quite small straws, but ostensibly both do relate to the referendum and to the general discussion of Scottish identity it brought about. They also seem to share a sense that our response is diffuse, muddled even – though in the CCA show some of the muddle may be the curator’s. It is billed as “a major curated programme of artistic responses to the Scottish Referendum.” “Major” is questionable, and only one of the five artists, Alec Finlay, actually reflects on the referendum. The work of the others, In the Shadow of the Hand (Virginia Hutchison and Sarah Forrest), Mairéad McLean, Antonis Pittas and Oraib Toukan, only have a tenuous relationship to it, if at all.

Advertisement

Hide AdAlec Finlay’s contribution is a better tale to tell: submissions to The Smith Commission. With his capitals, or lack of, it’s a ‘found’ poem, a collage of bits of text taken from actual submissions to the Smith Commission. Juxtaposing statements like “I voted No,” “I am proud to say,” “I voted yes,” reflects the divisions in the country. “Confidence has been severely knocked” and “There’s a sense of serious disorder in our communal life” are two negative comments placed nearby. There are more positive comments, Scottish voices and English voices, voices against Independence and voices for, voices for a federal solution, voices against Trident and fracking and much else and they consistently contradict each other throughout. If you look at the stars, the more powerful the telescope, the more stars you see. Looking this closely at the texture of the pubic response to the Smith Commission has the same effect. Overwhelmed by detail, there seems to be no scope for the generalisations that make politics possible.

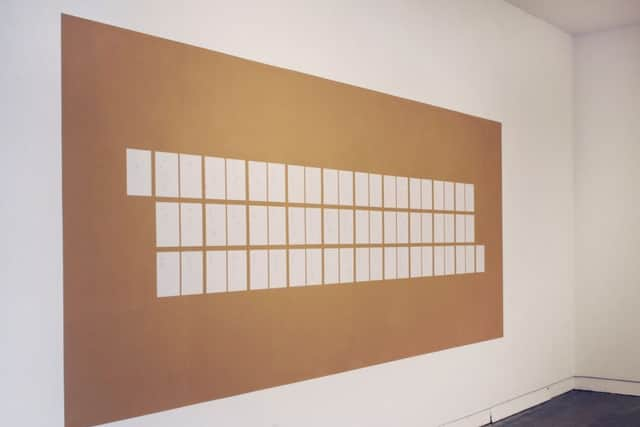

If only for that reason, Finlay’s poem is an interesting document, but I am not sure whether it is really a poem, or exhibition material either for that matter. It exists as a book and drifting elegantly across 64 pages in short, fragmentary lines without punctuation or capitals, it works rather well. So surely it is in a book, not on a gallery wall, that it belongs.

In spite of being billed as major, the rest of the exhibition is fairly sparse. The biggest work is by Antonis Pittas, a long beam of stone with the words projected on it, “Some people in this room simply want to shout down those who disagree with them.” Later in the exhibition’s run, rather enigmatically, this will change to “The people today reply to the right question.” Pittas is Greek so the referendum he is referring to is the one held in Greece earlier in the year. The rest of his contribution consists of gesturing hands, indicating disagreement no doubt, or at least debate, and to that extent they chime with Alec Finlay’s wider theme. I am not sure, however that “they undermine the notions of display, gestures of the political hand and a recycling of public language” as it is proposed they do.

Mairéad McLean’s father was interned in Northern Ireland and in No More, a video mostly of a man dancing and shifting periodically from positive to negative, she reflects on the Troubles there. The chilling voices of politicians are heard in the soundtrack and, we are told, “the dance is a bodily response to a political act”. If it is, it is pretty oblique and if it relates to the Scottish referendum at all, it is to remind us of the violence that lurks in the shadows of all such debates.

Oraib Toukan is Palestinian so she works against an even more violent background. Her contribution is a sequence of photographs of modern buildings, part of a forthcoming publication on “contested modernism” in Palestine. With the awful violence inflicted daily on one part of that unhappy state and the cruel indignities inflicted on the rest of it, any contest over modernism may seem a rather minor concern, but the existence of these buildings seems perhaps to be a sign of hope.

If these others relate at least to areas of political contest, the duo, In the Shadow of the Hand, seem to have wandered even further off the point. A video of two girls eating popcorn in front of an ancient structure half buried in the landscape is supported by two graphite skulls. If it proposes a contrast between transience and permanence, dare one say it, it does seem just a little corny. A long text nearby reflects on individuality, however, both historically and as it is experienced by each of us. This does perhaps have a bearing on the gap between the individual and the group that is inevitable in democracy and so in referenda. This is also apparent in Finlay’s piece and so, to that extent, they are connected, but as with his poem, is this really the place for such a text? It seems to confuse the intention with the act and in art at least realisation of any intention lies in the autonomy of the act: chrysalis and butterfly – this is still chrysalis.

Advertisement

Hide AdDocument Scotland is the ambitious title assumed by four photographers, Stephen McLaren, Jeremy Sutton-Hibbert, Coin McPherson and Sophie Gerrard. The Ties that Bind is a body of work they made working in and around the time of the referendum. In A Sweet Forgetting, Steve McLaren reminds us how the sugar trade created Scottish fortunes on the backs of West Indian slaves and how its legacy endures, although mostly unnoticed. Here are the great houses that the magnates built in Jamaica and in Scotland, schools and churches that they built, too, and modern Jamaicans with Scottish ancestry and a beautiful Scottish garden, poignantly but mysteriously named Slaves’ Paradise.

In When Saturday Comes, Colin McPherson has photographed some of the smaller Scottish football clubs, their supporters and their grounds, reminding us how, away from the mega-money of the modern game, football is still part of the life of local communities. Community is also very much the subject of Jeremy Sutton-Hibbert’s photographs of the Common Ridings of the Border towns, an ancient and dramatic expression of community.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe most striking photographs are Sophie Gerrard’s of women farmers. She has chosen half-a-dozen women working as independent farmers in various and often difficult conditions around Scotland. They all have interesting stories. Born on Eigg, Sarah Boden, for instance, became music critic of the Observer before returning to farm there, while Sybil McPherson, a lifelong farmer in Argyll, is regional chairman of the National Sheep Association. Gerrard’s pictures capture the lives of her subjects with candour and sympathy and give a vivid impression of the lives they lead. If, altogether, these works are bound to fall a long way short of documenting Scotland, like Alec Finlay’s poem, they are fascinating documents of small details of the country as it is now.

• The Shock of Victory until 1 November; Document Scotland until 24 April 2016