Art review: Mackintosh Architecture, Glasgow

MACKINTOSH ARCHITECTURE

Hunterian Art Gallery & Museum, Glasgow

Star rating: * * * *

When the architect of the new Scottish Parliament was chosen, the powers that be clearly thought that Enric Miralles, an “international” architect, would never produce a building that might encourage the foolish thought that with its parliament restored Scotland might once again think itself a nation. But Miralles was a Catalan and the Catalans have long recognised their parallel with the Scots. He also actually knew Scotland and its architecture very well and, in tribute, he based his whole design on a Charles Rennie Mackintosh flower drawing. Its stem grows out of the ground at the foot of Arthur’s Seat and its leaves and petals are the striking curves of the building’s plan. He also paid tribute, however, to the great Catalan architect, Antoni Gaudí. The sloping columns supporting the walls of the debating chamber come straight from Gaudí’s Sagrada Familia in Barcelona. Gaudi is the national architect of Catalonia and so clearly Miralles implied Mackintosh is Scotland’s national architect. Far from getting a neutral, international building, the bureaucrats and politicians got one that is twice national: Scottish and Catalan.

There is a delightful irony in that, but it is also interesting that Miralles links Gaudí and Mackintosh. Before the 20th century appropriated Modernism with a capital M as its own, the idea that art should be of its time, learn from the past, but not imitate it, and therefore be “modern”, had wide currency. In architecture it was a reaction against Victorian, eclectic revivalism. This idea of modernity inspired both Gaudí and Mackintosh and is the source of the striking originality of their architecture. (It is incidentally a nice model for our parliament too.)

Advertisement

Hide AdMackintosh Architecture, a display of architectural drawings at the Hunterian, offers a fresh insight into the work of our national architect, if indeed that is what he is. His drawings are often very beautiful, but here it is the professional architect we see in them and so, instead of the familiar image of a romantic young man with dark hair, full moustache and floppy tie, he is represented by Fra Newbery’s portrait. He is hatless and wearing an overcoat. He has no moustache, his hair is grey and he has grown a little plump. Newbery catches the alert intelligence in his face and with the plans of Glasgow School of Art in his hand, he is presented as a successful, established architect. There was a sad irony in that, however, for although he is now Glasgow’s principal cultural icon, in his lifetime the city rejected him. He left Glasgow in 1913 after the completion of the School of Art and built very little thereafter.

The portrait declares the intention of the exhibition to avoid the myth and focus on the work, not the man. The result is often surprising. In 1893, for instance, while he was making the fantastical designs that earned him and his friends the sobriquet the Spook School, as an apprentice in the office of Honeyman and Keppie he was designing an ash pit for two tenements formerly in Carrick Street, Glasgow and adding lavatories to each floor of their stair towers.

Honeyman and Keppie were good, professional architects. Their work was eclectic and they were happy to build in whatever style their client preferred. By the time Mackintosh joined the practice, Honeyman, the senior partner was doing less and less and as a gifted apprentice Mackintosh was evidently given an independent hand early on, but he naturally worked as they did. In 1901, for instance, he designed an extension to Aytoun House in Glasgow pretty much in the Italian Renaissance stye of the original building. It may seem surprising nevertheless to find him writing to a client in 1905, “If you want a house in the Tudor, or any other phase of English architecture, I can provide you with my best services.” His own sense of style was ultimately irrepressible, however. It is there in the detail of the Glasgow Herald building from 1894, for instance, but his imagination is even more strikingly apparent in the dramatic perspective drawing that he did for this project. The partnership also designed the Daily Record building in 1901. Here Mackintosh seems to have had a fairly free hand, but the impact of the design is also immeasurably enhanced by his spectacular perspective drawing.

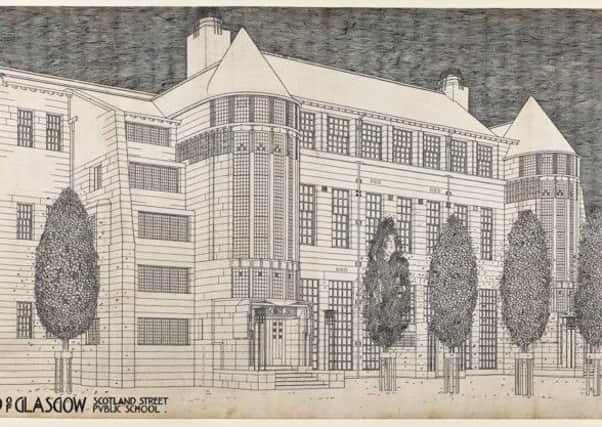

Recognising the dramatic impression such drawings made, the partners evidently encouraged Mackintosh to prepare competition drawings. One striking example is a proposal for Liverpool Cathedral made in 1901 or ’02. In outline it is a conventional gothic church, but closer to, especially in the tracery of the windows, he has let his imagination run wild. If it had been built, we might more readily see the analogy that Miralles suggested between him and Gaudí. The one church he did build, Queen’s Cross Church, does show some of this richness of detail, although it too is conventional in outline. In his dealings with the Glasgow Schools Board for the two schools that he designed, Mackintosh’s imagination proved to be an obstacle rather than an asset, however. His proposal in 1904 for what would in effect have been a glass wall as an improvement for his earlier design of Scotland Street School was rejected with some acrimony.

Already in 1901, no doubt in prospect of his marriage to Margaret Macdonald, Mackintosh designed a town and a country house for an artist and in these, working independently of the partnership, his characteristic style is fully evolved. The windows are asymmetrically placed and vary dramatically in size. The profiles of the walls slope inwards avoiding the rectilinear discipline of conventional architecture. These features are even more pronounced in his two major houses built in the following years, Windyhill and The Hill House. In them he looked to the massive walls, simple lines and asymmetrical compositions of Scottish castles and tower houses, but transformed them into something radically modern.

In 1906, he became a partner in the firm and for the next seven years was able to work more independently leading to his masterpiece, Glasgow School of Art. Here too, Scottish traditional forms were an important part of his inspiration. He also looked much more widely at the architecture of the past, however, and the exhibition of his architectural drawings is supported by a display of his sketches. This reveals how far he travelled in search of inspiration, but also what sort of buildings he favoured and how indeed he studied them to learn from them – not to imitate them as his Victorian predecessors would have done, but to create from them a modern style. The buildings he draws are often barns, cottages and country churches, strangers to the conventional architectural disciplines of symmetry and the perpendicular. He spent a long time studying the castle on Holy Island, for instance (before it was restored by Edward Lutyens). Its irregular massing, eccentric windows and battered (sloping) walls perhaps find an echo in some of his most characteristic later designs. The timber construction of a barn in Norfolk suggests the open timber roof of the gallery in the School of Art and indeed the barn’s brick ventilation windows offer a model for his signature chequerboard motif. A church in Dorset proves to be the model for the tower of Queen’s Cross Church.

Advertisement

Hide AdThese drawings are beautiful, but they are also a vital witness to Mackintosh’s insatiable curiosity and to the way his imagination worked, studying not just the shapes of buildings but the details of how they functioned. One remarkable drawing, for instance, is of the kitchen of a cobbler’s cottage on Holy Island analysing how the kitchen range worked and itemising the functions of its parts. This is indeed the work of Mackintosh the dedicated professional, just as Fra Newbery, artist and director of the Glasgow School of Art, saw him.

• Until 4 January 2015