Art review: Generation, Edinburgh

Generation

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art and Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh

***

For time, however, its success is less clear. It claims to represent the last 25 years of contemporary Scottish art, but a great many good artists are excluded, not because of space, but because they don’t fit the project’s narrow agenda. Although presented as comprehensive, it is actually highly partisan. The great majority of the artists are in their forties. Two or three are in their fifties. Except Steven Campbell, who would have been 61, none are older. Few are under 30. Most are Glasgow School of Art graduates from the Nineties. They are the generation this is really about. The rest is flannel.

Advertisement

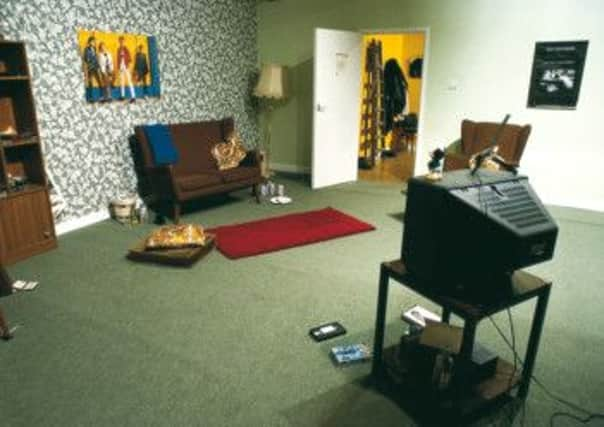

Hide AdThe National Galleries are at the heart of the project and their main show, involving 30 artists, is split between the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (SNGMA) and the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA). One of the most imaginative elements is a recreation in part of Campbell’s 1990 exhibition On Form and Fiction. Framed paintings hung and lit like cinema screens are set in a field of unframed monochrome works on paper to present Campbell’s constant concern with painting as an ally of cinema at the interface of truth and fiction. Nevertheless, this work is deeply concerned with painting and so hardly fits with the rest of the art on view, for on the whole painting is pretty much a stranger here. And, too, how can Campbell be included when his close contemporaries Ken Currie and Adrian Wiszniewski pointedly are not? There’s no logic in it. It is hard to find anyone to equal Campbell’s originality, but Christine Borland does come close. She too presents the elusiveness of truth with six busts of Joseph Mengele, the monstrous Nazi doctor, created by six sculptors, all working from the same remembered information, but with very different results: form is fiction, perhaps.

Less substantial in every sense is a puffy cloud of pink and blue plastic by Karla Black at the top of the stairs of the RSA: formless fiction?

David Shrigley’s black glazed welly boots and rough black woodcuts, however, are refreshingly forceful. On the other hand, Callum Innes’s beautiful abstract paintings, sufficient in themselves, are among strangers here. So too are Alison Watt’s four big drapery paintings at the SNGMA.

The label to Martin Boyce’s 2002 installation of fluorescent lights and steel mesh at the RSA tells us “This installation conjures up the idea or feeling of a place – the urban park at twilight as it shifts from the routines of the day to the wantonness of night...” Really? If anything it looks more like a half-dismantled prison yard to me, but who am I to quarrel with the authority of the label?

At GMA more labels tells us what to think. Simon Starling, we read, is “a great teller of stories”. He has built a henhouse modelled on a German building that served the Gestapo and has then used its timber to boil the eggs laid by the hens in an egg coddler designed in the Bauhaus. All true, no doubt, but the story exists only in the label. In ancient Greece, the Delphic oracle’s enigmatic utterances made little sense except through hopeful interpretation. Then as now, hopefully the labels interpret these mysteries for us. They do so, too, with a kind of breathless awe. Claire Barclay is another artist whose work is truly Delphic. She offers us no way in. Instead we are asked simply to admire her pursuing her private interests. Too often here, we are told that the artist is interested in this or that, but unless they succeed in making their art interesting, as Barclay conspicuously fails to do, it is an empty, solipsistic exercise.

But Ross Sinclair’s Real Life Rocky Mountain (also at SNGMA) needs no label. It is a brilliant, overflowing celebration of Scottish kitsch with rocks, waterfalls and stuffed animals, a nice piece for Referendum year. Charles Avery is much less convincing. He goes on creating his fantasy island in laboured pencil drawings. Some of the detail is amusing, but the whole enterprise has an unhealthy air of the boy’s bedroom about it. Graham Fagen’s stage set with, to hand, the script for a play with a lavatorial performance as its conclusion, is not as good as some later work. Conversely, some of Richard Wright’s earlier work, a little drawing called Deluge, for instance, is very beautiful, but too slight to justify his later reputation.

Advertisement

Hide AdKate Davis’s indignant take on de Kooning’s Woman paintings is persuasive, but Victoria Morton’s abstract paintings look to de Kooning for inspiration. Toby Paterson doesn’t actually paint, but inspired by the utopian geometry of modernist architecture, he gets close to abstract painting and one of two of his larger compositions are very beautiful. Alex Dordoy does something similar with paintings of yachts, though with much less point. Lucy McKenzie is another out of place painter. Her beautiful painted collages look back to the pin board still-lifes of the late 17th century, but here she has also added another link to the past in a lively baroque ceiling with statues seen from below against the sky and an impudent cat peeping over the balcony.

Henry Coombes’s The Bedfords is a short, surrealist costume drama. An amateur take on the films of Luis Buñuel, it is loaded with the pretensions of art, but wouldn’t survive a minute in a real cinema. Rosalind Nashashibi’s film at the RSA is much more sophisticated, but also raises the question of whether it is in the right place. Torsten Lauschmann’s collage of film and light show, on the other hand, is at least visually diverting.

Advertisement

Hide AdOther artists include Roderick Buchanan, whose preoccupation with football and sectarianism is really art as sociology and that is even more true of Jonathan Monk’s travel agents’ signs for cheap holidays. Jonathan Owen appropriates photographs to deface them with a rubber and turn film stars into ectoplasm. He also cuts up marble busts, again appropriating and defacing the art of others without apology. Douglas Gordon does the same in his 24-hour Psycho from 1993. The film slowly ticks away, its horror frozen. It is hypnotic, but it is also art feeding on art. There is too much in this whole show that either turns away from art altogether or turns inwards. It is as though, sustained for centuries by its role in the discovery of the world, but now exhausted, art has either abandoned the struggle or turned in on itself. Then like a starving organism, it starts to consume its own tissue. Paradoxically as artists give us less, we seem to look to them more to provide illumination. That is what inspires the breathless awe of the labels, but sadly illumination is far beyond the slender means most of these artists have at their disposal. There is some brilliant work here and some that may last. There is, however, also much that is overrated. Apart from Steven Campbell, there is no work of genius here. Too much of it feeds off a given culture and so is mannerist: everything has been said, everything done, and now we can only turn over the ashes, pick over the bones, or solipsistically turn inwards.

So what has driven this undoubtedly ambitious project? At the opening, Ben Thomson, Chairman of the National Gallery Trustees, gave the game away. “A quarter of recent Turner Prize nominees have come from Scotland,” he proudly claimed. I am not sure that we need share his pride. The Turner Prize has no universal authority. Dominated by a metropolitan clique, it has relentlessly promoted a very narrow vision of contemporary art. A group – a generation – in Glasgow have successfully tuned in to it. Good luck to them, but, in 2014 do we really need to look south for validation as this whole project implies?

RSA until 2 November; SNGMA until 25 January 2015