Art review: Boyce, Büchler and Hiller, Glasgow CCA

Sonia Boyce, Pavel Büchler, Susan Hiller: Speaking in Tongues

CCA, Glasgow

Rating: * * *

For weeks now our TV screens and our Twitter feeds have been filled with the most extraordinary scenes of storm tides and terrifying waves. In many of these images there is a poignant counterpoint to the towering walls of foam: in the foreground you can usually spot a tiny band of shrieking bystanders. But if recent weather conditions have been unprecedented, our current obsession with standing near a sea wall or on a pier and getting soaked turns out to be at least as old as photography itself.

Advertisement

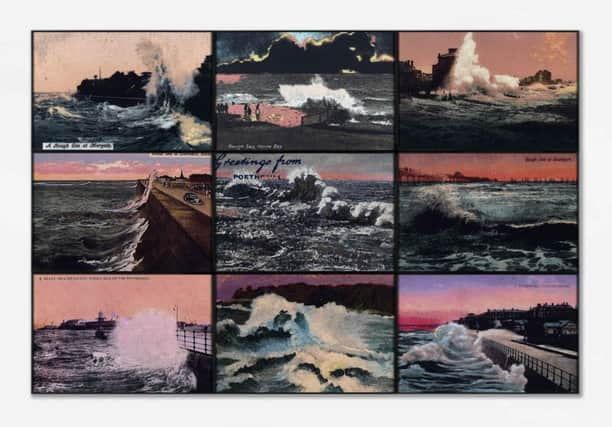

Hide AdBetween 1972 and 1976 the London-based artist, Susan Hiller, collected more than 300 postcards of British seaside towns showing such scenes, which often bore the label Rough Seas. The images turned out to be as popular in Victorian postcards as in recent times. Hiller, an American who trained as an anthropologist, applied the tools of her former trade. She laid the postcards in grids, analysed the words on front and back, expended what seemed to be a disproportionate amount of energy on what might have seemed a trivial matter. But the work revealed something of the deeply peculiar relationship between Britons and the sea and a kind of national masochism about bad weather that we can now see as a longstanding phenomenon. The final artwork, consisting of her archive and notes was named Dedicated to the Unknown Artist. For there was also something odd about the pictures themselves. If Britain had no shortage of rough weather or folk who wanted to stand in it or write a postcard home about it, the technology to capture it was often limited. On closer examination many of the postcards had been retouched, the vast spumes and broiling seas were the result of the human hand and not the hand of god.

Those rough seas have blown up again at Glasgow’s CCA this month, with a handful of the original postcards enlarged into a riotous display entitled Rough Sunsets. It is part of a three-handed exhibition in which the gallery has invited back key figures from the contemporary art world who showed there during the 1980s. The gallery text suggests that we think of the postcards as an early version of Internet memes. If I’m not quite buying that, that’s not to say that Hiller was not prescient – much of her early body of work turned out to be the template for the contemporary art of the next few decades, and her interests in the subconscious, in cinematic representation, and her presentation of archives as art works in themselves are now mainstays. One of her best-known works, An Entertainment, virtually invented the video installation as we know it today.

Hiller, of course, remains a working artist rather than a historical figure. At the CCA a series of works explore her longstanding interest in the phenomonena of spiritualism and of automatic writing, themes that have interested avant-garde artists since the late 19th century. A sequence of lightboxes shows the strange writings and drawings that figures from Victor Hugo to George Yeats believed to be the results of supernatural or subconscious forces,

The history of the avant-garde is also of interest to Pavel Büchler, a teacher and occasional writer as well as artist, who remains an important figure for Scotland’s artists after he taught at Glasgow School of Art. In his work, Nodds, two video monitors show tiny still images of Samuel Beckett, clumsily animated to make him appear to nod. It’s an enigmatic little piece, the great playwright trapped in perpetual motion, the kind of fate he might have written for his own characters. Büchler, who comes from Czechoslovakia, often plays with the ways that ideas travel, translate or are misunderstood as they cross borders, formats or simply cross our horizons. Now a professor at Manchester Metropolitan, among his many near invisible works is the Manchester Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. It was a joke of sorts, as it was simply an ordinary local bar, where people met for a drink at the Biennale in 2001, 2003 and 2005. But it was a serious endeavour in that it played with, and played havoc with, the elaborate hierarchy of national presentations.

At the CCA, his works are both simple and dense at the same time. Idle Thoughts is a sequence of 12 pages on which the artist wrote his diary day after day for a year. Each new word is written over the previous entries. The text is unreadable, so that it is the complexity of experiences and the sheer weight of time passing that is noted rather than the clarity of individual memories and experiences. Hung on the wall opposite an old Sanyo cassette player plays a tape. The tape is of the clacking sounds of typing. The sound is a typist transcribing an old forgotten tape of two artists in conversation. On the wall you can now read the clumsy typewritten transcript. The technology is obsolete, but somehow in the process a lost history has been made visible again.

In a coda to a show that is often austere, Sonia Boyce also marks the forgotten or the sometimes invisible with her joyful work, The Devotional Collection. Friends and colleagues have contributed to her ever-growing archive of black female musicians who have made their careers in Britain. The result of a chance conversation some 20 years ago, The Devotional Collection allows you to browse magazines or play some great records, whether you like pop, soul or punk. It feels like a necessary balance, because while Speaking in Tongues, is a stimulating show of art about ideas, sometimes you also need pleasure, or something like good music, to break over your head like an enormous wave.

Until 23 March