Art review: The Amazing World of MC Escher

The Amazing World of MC Escher

Star rating: ****

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh

Let’s get this clear from the start. This is an excellent, well-researched, and in some ways, groundbreaking exhibition of some of the most popular graphic art of the last century. It is the must-see show of the Edinburgh summer.

But while we’re at it, let’s get another thing sorted too. It is also a show of dry, self-regarding work by an indulged, and at times depressingly dried-up-prune of an artist who barely raised his head from his drawing board to watch the terrible 20th century whizz by.

Advertisement

Hide AdDid you see what I did there? The Amazing World of MC Escher is, like the 100 prints, drawings, woodcuts and lithographs it consists of, an unholy bundle of contradictions. Or to be more precise, the emotions it generates are themselves like the “Escherian double take”.

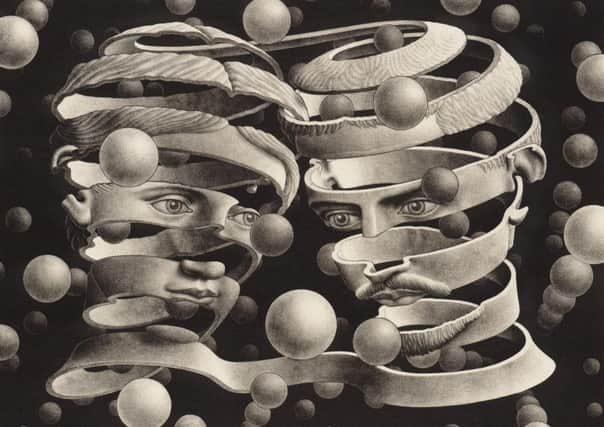

Maurits Cornelis Escher (1898-1972) was the enigmatic Dutchman who started out as a late art nouveau apprentice and ended up, through neither fault nor ambition of his own, the emblem of Sixties pyschedelia. He used his amazing technical skills, his interests in non-Euclidean geometry and his brother’s professional achievements in crystallography to persuade viewers to see seemingly irreconcilable contradictions in one take.

How could that mirror show the reflection of the street instead of the room? Is that a floor, a wall or a ceiling? How does water flow upwards in Waterfall?

This show has been accompanied by both a triumphalism that it actually exists (there is, apparently, only one Escher work in a public collection in the UK, it belongs to the Hunterian at the University of Glasgow and it got there by accident – it was the Geography department that acquired it) and a rather disingenuous harrumphing that Escher isn’t better loved by the museum world, as though museums were the arbiters of everything.

But it’s perfectly possible to think that Escher is both a brilliant image-maker and an awful artist. Twentieth century art was a social undertaking; a violent battle of codes and cliques, a connected and communal activity. Art wrestled with the world, not just as it looked but also as it was experienced. Escher was something else, a producer of perfect puzzles, and a patient cabinet-maker with a pencil.

If he genuinely and laudably explored the mathematical underpinnings of the universe, the attempt to draw deeper meaning in Escher’s work is often embarrassing. His wartime image Reptiles (1943), the famous still life in which a clutch of miniature lizards crawl from the flat plan of a drawing on a table top into three-dimensional fire-breathing life, was once thought to refer to the biblical trials of Job. The catalogue explains that no… it just so happened that the Job cigarette papers on the table were the most popular brand in Belgium where the Escher family had lived.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe exhibition is chronological and it is instructive to see Escher’s journey. The early self-portraits show a wealthy, self-regarding young man rather keen on his own image. We learn about the influence of Japanese screen techniques to create depth, his trips to Tuscany and Corsica, where the dizzying perspective of mountain and cliff-top villages must have been a revelation to a flatlander from the low countries, and where Escher first tried out simultaneous viewpoints, reconciling the bird’s eye view with that of the worm.

At the Alhambra and in Cordoba in southern Spain the dizzying impact of Islamic art and tiled splendour took him forward in developing tessellations, the complex visual patterns that became his signature. But there’s something rather sweet and chastening about discovering that some of the most complex of his visual puzzles were not sourced from the great examples of world architecture but in the white-walled hallways, dark stairs and corridors of his rather gloomy school in Arnhem.

Advertisement

Hide AdThere are works here that are such perfect examples of Escher’s intention that it is a thrill to see them in the flesh. Drawing Hands, in which the left-hand draws the right and vice versa, is an autobiographical summary of the left-handed artist’s own work with mirrors and devices and the reversals created by printing techniques, but also the perfect explanation of the strange meta world of all visual fictions.

But there are plenty of things, like the awful faceless figures, the strange invented lizard-like creatures he called “curl-ups”, the shameful stereotypical slit-eyed Chinese boys and the embarrassing gnomes that populate some of his works, that you wish never to see again.

It is hard to imagine Hogwarts without Escher, or the graphic imagery of much heavy metal, or the truly fantastic work of English album cover artist Storm Thorgerson. Isolated from artistic and wider cultural life, Escher didn’t partake in the cultural reception of his own work unless on his own terms. Famously he refused Mick Jagger’s request to use his work, and drew a blank at the name Stanley Kubrick when his people called. Interestingly, his current triumph perhaps sits better in the age of computer games, of solitude and solipsism and feedback loops than it ever did in the adventurous, transformative era of psychedelia.

Escher’s work doesn’t need the imprimatur of the museum curator to make it respectable. We can love Escher for what he was and did without ever needing to think he is a great artist, or a fine artist at all, for that matter.

Along with his technical excellence we must recognise his limitations. This brilliant exhibition highlights his strengths but it also exposes his dreadful weaknesses. I enjoyed this show. I learned a lot. I just wish that it could be a lot more fun and vulgar and rather less hushed and reverential.

• Until 27 September