Alexander McCall Smith: Why you can't trust '˜books of the year' lists

Every year at about this time, if you happen to be somebody who writes books, you hear from the literary editors of various newspapers or magazines. Their message usually starts with that classic apologetic formula: “It’s that time of year again ...” This heralds the request for a small piece – usually no more than 200 words – on the books that you have particularly enjoyed over the year.

The temptation that faces anybody who receives this request is rarely admitted to, but it is certainly there. Which one of my friends/cousins/lovers has written a book this year? The answer to that may provide the necessary inspiration to respond to the editor’s demands. After all, if an author can’t expect a friend to nominate his or her book as a book of the year, then what sort of friendship is that? An alternative question, of course, may be: Which one of my enemies/rivals/hostile reviewers has written a book? By nominating a book by one of these – and the ranks of these people will always be legion, given the nature of the literary world – you may be able to induce a deep sense of shame in those who have wronged you. It is always better, after all, to treat those who despise and dismiss you with the utmost courtesy and consideration. Nothing will make them feel worse than that.

Advertisement

Hide AdOf course, neither of these options is acceptable, and so you then have to wrack you brains to try to remember whether you have read any books during the course of the year. Now there are many people, including many authors, who read nothing at all. Such people experience a momentary panic when asked to choose their book of the year, but this panic need only be temporary. It should be borne in mind that the question you have been asked is not what book you most enjoyed reading over the year – it is, rather, what book you consider to be the book of the year. That is something quite different. It is perfectly possible to choose as book of the year a book that you have never read, but that you nonetheless consider to be the best book of the year. This is not unlike the very common habit that people have of expressing an opinion on books that they have never so much as opened.

Publishers are very much aware that their lists include books that sell very well but that are read by virtually none of the people who buy them. These books often win literary prizes and are described as challenging, or seminal, or even vital. They are usually published with various quotes on the cover from a number of the author’s friends (or relations) in which the book is described as a work of life-changing importance. Such quotes usually do not refer to the book’s content, for the simple reason that the person providing the endorsement has not read the proof copy sent in advance by the publisher, and has no idea of what the book is about. That will not in any way prevent an enthusiastic endorsement.

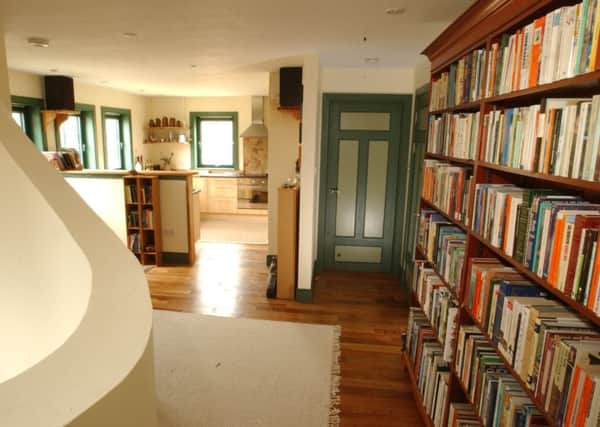

But if, when faced with a request for a book of the year piece, you remember that you have indeed read some worthwhile books over the course of the last 12 months, the next task is that of remembering where you put them, and this in turn raises the issue of the storage of books in the house. For many people, this is a very painful and complex issue that I should like to return to in a future column, when we might consider that classic pamphlet Lunacy and the Arrangement of Books. Unless you are one of those people who arranges your bookshelves alphabetically, you may find it very difficult to locate books of the year lurking among many books that clearly are not going to be books of this or any other year.

Another approach is simply to think of an author known for his or her consistency in producing at least one book of high quality every year. Then you can write something like, “The latest book by William Dalrymple is, in my view, head and shoulders above all other books published this year. It was a cracking good read and it does much to advance our understanding of the subject.” What subject? one may ask. Well, that does not matter too much, and it is not helpful to produce a spoiler in a books of the year column. So, if Willy Dalrymple has written a book this year – and he must have – it will certainly be my choice for 2018. If he hasn’t, then he is bound to write one next year, and one can always claim to be talking prospectively.

Having said all that, there is a wonderful book published this year by Madeline Miller, Circe. This is a Homeric novel. Every year there are several novels based on Homer’s Iliad or Odyssey, which were books of the year about 2,800 years ago. Circe is memorable, and I shall choose it if asked to nominate a book of the year this year, which is unlikely, I suppose, after this piece. That’s the trouble with frankness – it closes down so many opportunities. Oh, well. Give Circe a try. One of the best books of the year. Honest.