Art reviews: Counted: Scotland's Census 2022 | Lorna Robertson | Rhiannon Salisbury

Counted: Scotland's Census 2022, Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh ****

Lorna Robertson: Thoughts, Meals, Days, Ingleby Gallery, Edinburgh ****

Advertisement

Hide AdRhiannon Salisbury: Chthonia, Arusha Gallery, Edinburgh ****

It seems appropriate given its brief that the Scottish National Portrait Gallery has echoed the national census conducted earlier this year with a show called Counted: Scotland's Census 2022. It is not an obvious subject for art, although there is one great European masterpiece that does have a census as its subject. It is one of Pieter Brueghel’s finest winter scenes, his painting of the Numbering at Bethlehem. It was in order to be counted – and also to pay tax – that Mary and Joseph were travelling to Bethlehem. Where the picture shares common ground with its modern equivalent is in its thronged diversity. The Holy Family arriving to be counted are lost in the crowd who are nevertheless all individuals, each fully engaged in their own life. There is a soldier in armour peeing against the wall. One of my favourite details is an old woman who has come out of her dilapidated shack to pick Brussels sprouts in the snow. These people and countless others yield no precedence to what subsequently came to be regarded as a pivotal event in history. It is that same sense which the SNPG has sought to capture: a census as a mass event, yet one in which individuality is key to the success of the outcome.

It is an exhibition exclusively of photography. Most of it is contemporary, but there is also a scattering of historical images going right back to the beginning of photography with Hill and Adamson’s marvellous pictures of the fishing community of Newhaven. This makes the point that photography is intrinsically anti-hierarchical and so the natural ally of the approach that a census requires. But to be meaningful a census also needs fixed points in space and time: who is living where on a precise day, as at Bethlehem on Christmas Eve. This entails family and home and so among the first images is a big picture of the extended family of Amar Latif in Glasgow by Verena Jaekel. Alongside are touching Victorian family pictures, all their names are lost, but they are still identified by the towns in which they were made. Opposite and in contrast to the 14 people in Amar Latif’s family is a group of pictures of single parent families from a series by Amara Eno called Twenty Five Per Cent. That is the proportion of all families brought up by a single parent.

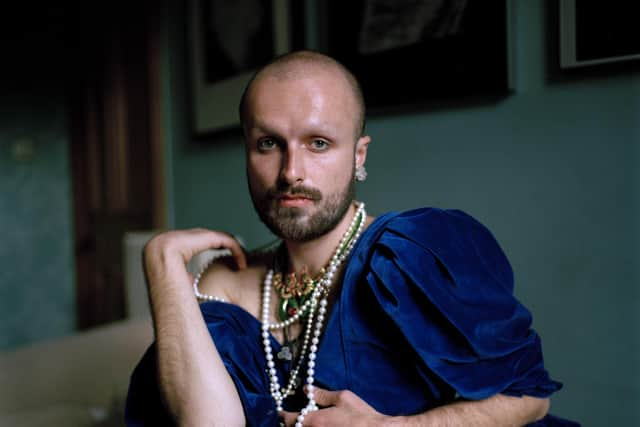

One of the most poignant sets of images concerns identity. It is from an autobiographical series by Edyta Majewska called Other White after one of the available categories of self-identification in the census. The series records the photographer’s experience of acquiring British citizenship. One picture, set against a wallpaper mosaic of a single image, shows her working for the minimum wage cleaning a polling station. This was in preparation for the Referendum of 2016, and she realised she was preparing the way for a vote that threatened her own future. Though the sitters are not named, two very fine portraits from the series Scots Jews: Identity, Belonging to the Future by Judah Passow are on the same theme of identity and reflect too a long history of insecurity. Dealing with another kind of identity, the non-normative or queer, six large rather wonderful portraits of cross-dressed individuals are from a series called Masc by Craig Waddell.

Most of the pictures are set in urban contexts, but several of Paul Strand’s portraits of the people of the Hebrides are set alongside a set of pictures called As I found her, by Danny North. They show members of the community of the Isle of Eigg, since 1997 freed from the blight of landlordism and managing their own affairs. These are mostly pictures of children. Indeed one of the most touching pictures in the show is a portrait of a little girl reclining on her hammock with a teddy bear against the misty landscape of Eigg. In its special context, it really is an image of possibility and of hope. Equally striking is a picture by Kieran Dodds. It is from a series called Gingers. The Scots have a larger percentage of redheads than most, but, identity again, Dodds’ point is it is not exclusive. His sitter, Alexander Soued, is a wide-eyed little boy with red hair. He lives in Inverness but his parents come, one from Eastern Europe and the other from the middle East. If the census records our diversity, it also suggests how enriching that is.

At first sight, Lorna Robertson’s big, semi-abstract paintings at the Ingleby Gallery might seem to be a very different enterprise, but at a certain level they too seem to be about identity, or at least about resisting the relentless generalisation of images of women which militates against their identity and individuality. The show consists of a group of six paintings in the main gallery supported by two more paintings hung in the stair and ten small drawings. Four of the paintings are big, horizontal canvasses. The other two are smaller and more or less square. Robertson paints on the back of a primed canvas. The effect is rather different from painting on unprimed canvas. The surface seems harder and less absorbent, almost scratchy, and this gives her paintings an improvised, provisional look, verging on gestural abstraction.

Advertisement

Hide AdTry see, try say, for instance, one of the big pictures, is covered in apparently random, mostly vertical marks. It looks abstract at first sight, but gradually something like an urban space takes shape, populated with flowers and a ghostly female figure. (The title is a quote from Samuel Beckett.) We are the Robots uses similar imagery but is more specific. It presents a row of women, or mannequins in a shop window behind a row of flowers in tall vases. The analogy is simple. Saints and Liars is one of the small paintings. It is also more legible and clearly shows a table top set with china and flowers, framed by roughly cut collaged canvas suggesting printed fabric. It seems to be a classic image of domesticity seen as a feminine province. It is rough and scratchy. She talks about avoiding sweetness and indeed she does, but she also seems to accept this image for what it is. Elsewhere her rejection of stereotypes is more emphatic and unambiguous. Dumb is a row of four mannequin figures with Dumb in large capitals written above their heads.

At Arusha Gallery, Rhiannon Salisbury’s exhibition declares similar preoccupations with its challenging title, Chthonia. Chthonia was an Athenian princess who was sacrificed by her father. Salisbury’s paintings are lush where Lorna Robertson’s are dry and scratchy, but she too paints female figures emerging from a confused image, or indeed apparently being dragged down into it as they are for example in Descending, or in Tangled Weed Pulled Me Under. She also paints poisonous or simply unpleasant plants like thorn apple and poison ivy. So much for flowers as images femininity, a perspective she shares with Lorna Robertson, and indeed one of her most striking pictures is of the evil smelling corpse flower. It is altogether a rather wonderfully outspoken group paintings.

Counted runs until 25 September; Lorna Robertson until 17 September; Rhiannon Salisbury until 2 October