Book review: A Book of Noises, by Caspar Henderson

Even though the idea of “Nature Writing” has undergone a transformation in the past quarter of a century, it is still thirled to certain tropes and priorities. Setting aside questions of bio-ethics, the Anthropocene and irreversible tipping points, as a genre, nature writing is predominantly visual. It is rooted in metaphor and simile. Footage of the Trinity nuclear test is visceral in a way that tinny recordings of the blast seem like draft versions of sci-fi soundtracks.

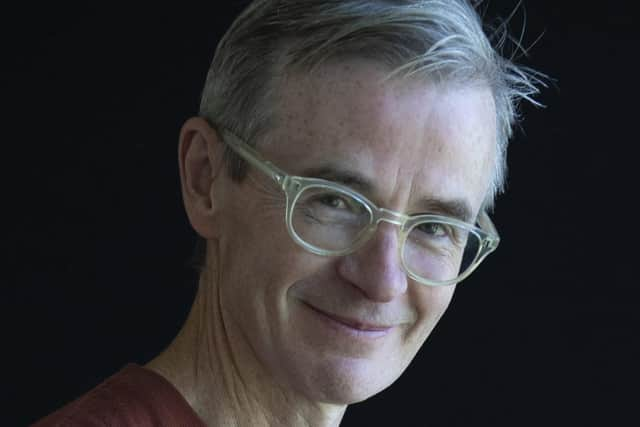

In this book, Caspar Henderson aims to shift our focus to the world of sound. In the wrong hands, the story he has to tell could come across as an arch combination of 17th century eccentrics like Browne and Burton and the hyperactive, hyperbolic style of most television nature documentaries. Instead, this is an immensely measured book, where the idea of wonder emerges naturally. It us subtitled “Notes on the Auraculous”, a neat neologism on miraculous, and also a mild rebuke on the notion that some of the material here is outwith the natural. (There are, of course, exceptions).

Advertisement

Hide AdSo, to start with some truths of which we are automatically distrustful: baby sperm whales have a cetacean equivalent of “goo goo ga ga” before we get whale song proper; live flames have been shown to move sympathetically to Schubert; and elephants hear through their feet and also grieve through them. We are accustomed to the immensity and diversity of shape, colour, magnitude and the microscopic, but are tone deaf or stone deaf when it comes to noise, music and silence.

It is an eerie thought that around 300 million years ago, living beings began to make sounds. The world was silent except for wind, rain, thunderstorms and volcanic eruptions. But a kind of grasshopper, permostridulus, was discovered in amber tens of millions years old. It featured the raised veins which, when rubbed together, create the familiar chirrup sound. There are two contrasting theories for such “palaeozoic intersex calling interactions”. Both are essentially by-products of a solution to a different problem. Either the insects are making themselves sound bigger to trigger more nectar, or they are to signal presence and mark territory. Henderson is charmingly cautious about explanations while remaining a committed Darwinian. I would duel with anyone who can listen to the dawn chorus and think, “Oh, they’re just marking their patch or showing off to the females”. I don’t sing Die Zauberflote in the shower as a “keep out” sign or to lure my Papagena. Are some animal noises merely expressions of pleasure?

Part of the picture is confused by elisions between taxonomy and hierarchy. Can anyone reliably identify indigo? How good an a ear do you have to have to differentiate C-sharp and B-flat? Or is there something aesthetically pleasing built into triads, fives, sevens, dozens and other numbers it pleases us to see as an unseen order? Imagine the brouhaha if CERN announced a definitive atomic number and it was a prime.

Henderson’s taste in music is gloriously eclectic, taking in McCartney’s Blackbird as well as Willie Ruff and John Rodgers’ musical version of Kepler’s the Harmony of the World, which the New York Times helpfully described as making a six year old dizzy and as “cacophony of tweedling, wailing, thumping and droning”. Its co-creator later called it tiresome, but you learn something even from a failed experiment, like Darwin playing the oboe to earthworms. Henderson is much more generous to Max Richter’s Sleep – I think I have heard all of it, but part of its glory is its soporific nature.

Every page in this book has a fact or observation that trills in me and thrills me. Henderson could, I think write on anything: it is not the data he imparts but the glee with which he does so that enthralls.

A Book of Noises, by Caspar Henderson, Granta, £16.99