Scotland's universities are crucial to wider economy but Tony Blair's home truths aren't the only sign of trouble – John McLellan

And for thousands of young people just emerging from lockdown, this is the stress season; the first full exam programme since 2019.

Nat 5s and Highers, college and university exams and finals loom, each one a staging post for hopes of a bright and prosperous future. And it’s what constitutes a prosperous future that has driven debate about the future of higher education.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIs it prosperity for the individual or the country as a whole? Do the two amount to the same thing? Is prosperity only to be measured by future financial benefit, or should it include the current buzzword of “well-being”, however that is calibrated?

Is there not a broader social benefit from people being happy in what they do, even if there’s not much dosh in it? And, of course, who pays for it all? Should all tax-payers shoulder the responsibility because ultimately everyone gains from a well-educated workforce, or should it be those individuals who go on to enjoy higher than average earnings?

The latter question appears to have been settled in Scotland, with all main parties, since the last Scottish election including the Scottish Conservatives, agreeing there should be no undergraduate tuition fees, following then First Minister Alex Salmond’s adaptation of Burns in his declaration that “the rocks will melt in the sun” before Scottish students paid for their teaching.

The cost of that commitment in 2022-23 will be £328m, yet the umbrella organisation for higher education, Universities Scotland, points out their total budget is being reduced in real terms, and since 2014-15 the Scottish Government’s funding had fallen by 13 per cent, with £869 less spent on teaching each undergraduate.

“This leaves universities with less resource to meet the very real needs of our students and staff and less resource to invest in university research as a driver of economic growth,” said the Universities Scotland convener Sir Gerry McCormac.

Total Scottish university funding actually rose by £21m, but the extra money is needed to cover the cost of teaching the extra students who qualified because of the inevitable grade inflation from replacing exams with teacher assessments during lockdown.

Better than predicted pass marks might explain the fall of students entering further education down from 28.1 to 23.3 per cent of Scottish school leavers in 2020-21, but they now face a cut of £51.9m through inflation and the end of emergency funding.

The result for them will be the same as the universities: fewer course choices, bigger classes, reduced contact time, and more pressure to streamline assessment. I’m only a part-time lecturer and as Stirling University’s Principal, Gerry McCormac is my boss (you’re doing a great job, sir) but he and I both know that at the sharp end of undergraduate teaching those effects are very real, on top of ever-increasing administrative demands.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUniversities are becoming the meat in the sandwich between a recognition that a better educated workforce and cutting-edge research is the key to economic growth, and being expected to do more with fewer resources at a time when, if the International Monetary Fund is to be believed, the economy will be desperate for a boost.

If UK growth will stagger to just 1.2 per cent next year, as a lag Scotland will almost certainly be even slower, but universities can’t deliver instant results and like laying down whisky or wine need investment now to produce results years from now.

Otherwise, they will produce new degree programmes designed to pass popularity tests, not focussing on what the economy needs, a numbers game in which students become the raw material in a factory producing goods for which there is no guaranteed market.

Yet, the Scottish record for technology businesses spun out of universities is good, with Edinburgh, Glasgow and Strathclyde in the top 20 in the latest Beauhurst/Royal Academy of Engineering survey, and Heriot-Watt and Aberdeen at 21st and 22nd, but that should be expected because Scottish Enterprise supports 232 spin-out ventures, considerably more than any other investor, so the building blocks for increasing the higher education impact on the wider economy are there.

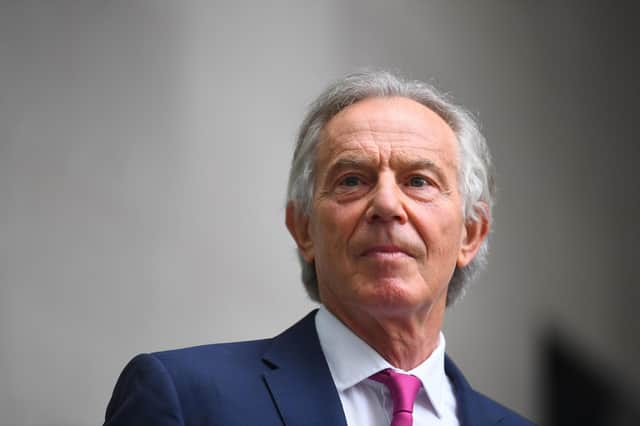

Into the fray has stepped former Prime Minister Tony Blair, whose Institute for Global Change published a paper this week calling for the number of school leavers going to university to be increased to 70 per cent by 2040, to match the proportion in “high-innovation” economies like Japan and South Korea.

The principle is sound but the implications in Scotland where the resources must all come from general taxation are vast, given the latest Scottish Government data on school leaver destinations, shows 45.1 per cent in 2020-21 went into higher education, up from 44.2 per cent the previous year.

By a very rough calculation, if that 0.9 per cent increase in undergraduate numbers equates to the £21m extra the sector is to receive, then the Scottish Government would need £580m at today’s prices to pay for a 25 per cent leap in undergraduate numbers, a quarter of the current £1.9bn colleges and universities budget. Cash switched from further education wouldn’t come close to covering the cost of four-year degree programmes.

Although widely criticised, the Blair proposal does contain some home truths, such as deteriorating educational attainment in school, substantial and worsening shortages in high-skill occupations, and the reform of courses which don’t build valuable skills, and if anything the problems in Scotland run deeper.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA political barrier to increasing funding, a limpet-like adherence to an out-dated and needlessly costly basic degree structure, and a faster decline in literacy, numeracy and technical standards in schools all need addressing to level the playing field. For Scottish universities, the stress season is likely to last for years.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.