Misogynistic media reports that victim-blame women who have been raped or murdered must be challenged – Karyn McCluskey

First impressions matter. They shouldn’t, but they do. There’s a school of thought based on scientific surveys that says it takes around seven seconds for our brains to form an impression after we first meet a stranger. And most of us take about half a minute to decide a person’s nature. It all feels remarkably shallow. For those of us who take a while to warm up or hide our talents until we know others, that’s a problem if we are interviewing, dating or taking part in other social interactions.

What if the impression is led by a third person? It’s a fair guess that few of us have met Donald Trump or any public figures, but your view will have been shaped by what’s written about them or what you’ve seen on TV, which has all been curated by someone else.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI love the movement online, where people change inaccurate, biased or just plain offensive newspaper headlines to reflect the reality of the crime that’s occurred. A recent example was when children and young girls, raped and sexually abused by grooming gangs, were referred to in some media articles as having “had sex with more than 100 men”. This odious representation of these horrendous crimes was quickly changed and shared by that online community.

Humanising murder victims

These headlines create a ‘first impression’ of those who’ve been harmed leading us to make value judgments about their worthiness and value, promoting victim blaming. It’s a story as old as time: ‘the fallen woman’. In 2024, we should have moved far beyond this, but here we are. Misogyny writ large.

Creating these impressions in the public mind can impact whether people come forward with information which could help solve serious crime, as well as play into conscious and unconscious biases about the importance of the victim or perpetrator.

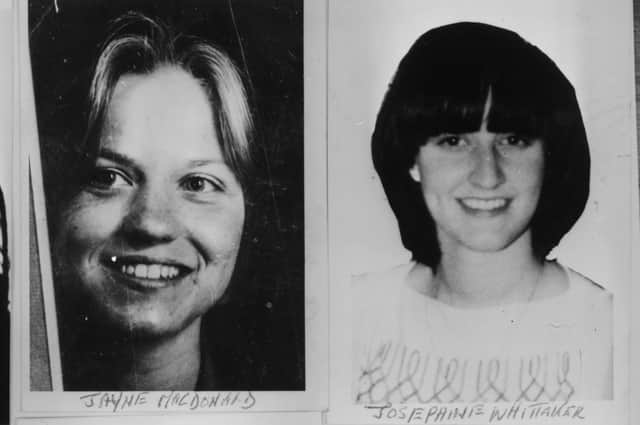

Tropes around ‘prostitute’ and ‘drug addict’ still feature in media depictions of victims. A ropey photograph (and we all have those) can cement an impression and indeed an investigation (literally). Peter Sutcliffe’s victims – and, closer to home, the three women murdered in Glasgow by the nebulous ‘Bible John’ – were all othered by descriptions in the press. Audrey Gillan’s podcast on Bible John has done much to humanise the murdered women, but comes too late for the victims’ families.

The media have critical importance when it comes to raising the profile of heinous crimes and filtering information into communities in a way which could lead to detection. I speak to journalists often about the role of the headline – the first few lines of a news article that draw you in (and often the only words read by many readers). These are the seven seconds of reading that set the impression and shape our ideas and interest. We need to make those seven seconds of reading count; for it to be accurate and full of human connection.

Journalism has the power to move us, but we all need a moment of hesitation when we encounter the clickbait headline. Stop and question who you are being asked to judge, and why. Not everyone can be a journalist, but we all have the power to rewrite the first impressions for those who need it most.

Karyn McCluskey is chief executive of Community Justice Scotland