Birth of CSI style forensic evidence did not go down well with some of Scotland's 19th century judges – Susan Morrison

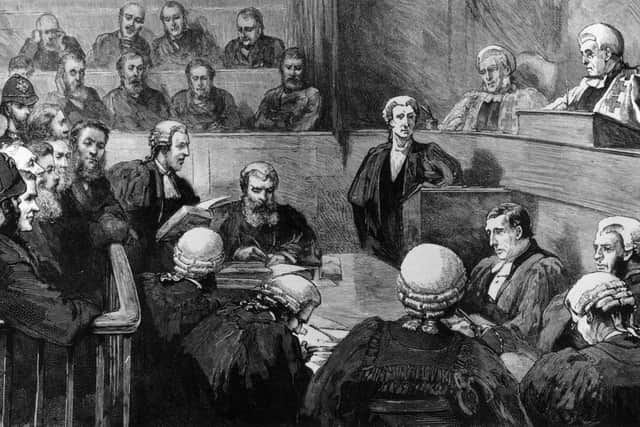

Scotland’s Victorian courts were pure theatre, and a murder trial was the hottest ticket in town, as Dr Kelly-Ann Couzens, a historian at the University of Western Australia, has been uncovering in her research. Court police regularly battled over-enthusiastic crowds swamping the public gallery. Those who did get a seat probably weren’t very comfortable. The judges liked their comforts. Huge blazing fireplaces kept the judiciary cosy, but must have made the atmosphere stuffy. No wonder His Lordship occasionally nodded off.

As the 19th century moved on, those judges in their blazing bright red robes and their white wigs increasingly found themselves facing a new creature in court, the black-clad medical man, bringing expertise on bloodstains, poisoning and decomposition. A few really didn’t like it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne of several case studies investigated by Dr Couzens concerned the 1890 trial of Giuseppe Colacicco, an Italian organ grinder, who was accused of stabbing James Kane, an Irish labourer, with Lord Young presiding.

There had been an argument in the Grassmarket, the witnesses said. They were deeply shocked by the killing. Giuseppe was not known for violence. Drink, however, had been taken. Kane suffered a violent death. Today we would expect a medical report. Lord Young, however, saw no need. When Colacicco’s advocate, Mr Guthrie, called his next witness, Dr Alexander Bruce, Lord Young was unimpressed. Judge and lawyer crossed verbal swords over the use of this testimony.

The Scotsman’s man in court reported the cut and thrust of the argument: Lord Young: “Upon my word, I do not see the use of medical evidence here. The deceased was stabbed by the prisoner and died from the wound... I suppose that is not in dispute – that he received the wound at the hands of the prisoner?”

Mr Guthrie: “No, my Lord.”

Lord Young: “Then what in the world is the use of having medical evidence?”

Mr Guthrie: “A medical man will tell us about the deceased’s stomach, liver and kidneys (laughter).”

Dour, dark Scottish doctor

Despite the unenthusiastic judicial welcome, Dr Bruce started his evidence. Lord Young couldn’t help himself, interrupting to ask if the state of the dead man’s face was relevant and was there anything of importance in this report? Dr Bruce ploughed on until he announced that the "deceased died from haemorrhage, the result of the wound”. Lord Young, clearly unimpressed, barked: “We could have had all that in the space of a moment.”

Today we would be deeply shocked at such scant regard for expert witnesses in a murder trial, but in the 19th century, skilled reporting from doctors wasn’t always welcomed by the judiciary. The doctors knew that, but they were also only too aware of the vital role they played in court. Their evidence could send a man to the gallows for murder. The way you played your hand in the witness box was crucial, and maintaining your cool before a cranky judge was utterly vital. Presentation was as important as the hard facts.

Men such as Robert Christison, Sir Andrew Douglas Maclagan and the near-legendary Dr Henry Littlejohn began to engineer that most iconic of figures, the dour, dark Scottish doctor, especially the pathologist. Edinburgh University was the first in the UK to set up a “Regius Chair of Medical Jurisprudence and Medical Police” in 1807. Originally in the School of Law, it aimed to improve the forensic examination of crime, before moving to the School of Medicine in 1822.

Pioneering poison tests

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdForensic medicine made impressive leaps in the 19th century, particularly in the field of toxicology. Just as well, since poison had a bit of a day of it in Victorian Scotland. It was an easy way to dispose of a well-insured lodger or wife. Poisons of all kinds were readily available in 19th century homes. Cleaning products and household cures for common ailments contained ingredients such as strychnine, arsenic and prussic acid.

Doctors like Littlejohn pioneered new tests to uncover what really killed that wealthy relative. Explaining the methods of detecting and the resulting outcomes calmly, steadily and clearly in a court of law so that judges and a non-medical jury could understand became as much a part of the doctors’ training as the medicine itself. Everything counted, from their clothes to their voices.

Littlejohn, always clad in sober black, recommended monochrome for court appearances. He was also fond of deploying his dry humour and never hesitated to turn it on judges and lawyers.

The voice was a vital tool. Sir Douglas Maclagan, in 1880, encouraged his students to always "speak loudly and distinctly... avoid using technical expressions [and] ... avoid using metaphors”. The Scotsman's obituary of Dr Christison in 1882 fondly remembered that he was “gifted with a magnificent bass voice”.

Penal servitude better than Grassmarket

Failure to communicate could earn a crackling reprimand from the bench. Dr Gilmour of Linlithgow was called to be an expert witness in an 1889 trial. A tourist had been brutally murdered on Arran. There were competing accounts of the man’s death. Dr Gilmour, a man with a distinguished military medical career, blew his chance in court and gave a long, rambling forensic report of his examination of the body. He couldn’t be heard and used jargon. The Scotsman recorded that “Lord Justice-Clerk hinted at some of the terms used as being ‘Greek to them’, an observation which created some laughter.”

If your expert got the science and the presentation right, there was no laughing. Dr Couzens describes these dark clad doctors as men of “persuasion, authority and medical expertise”.

Oh, and Giuseppe Colacicco, the Italian organ grinder? Lord Young pronounced a sentence of penal servitude for seven years. The Scotsman reported that His Lordship had added that after the prisoner was “liberated from penal servitude, he hoped he would return to his own country… [and] in penal servitude he thought his life would be less miserable than in lodging in the Grassmarket and spending the day on the streets as a noisy beggar”.