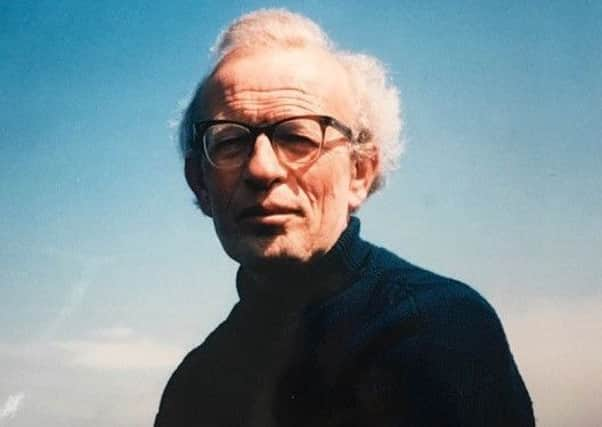

Obituary: Dr James Herbert Robarts, war veteran and GP whose interests included ornithology, botany and painting

James Robarts was one of a dwindling generation whose extraordinary breadth of knowledge and experience, coupled with an unshakeable sense of service, is virtually unmatched today.

Long before he served on the wartime convoy that made a major contribution to unlocking the Enigma code, he had developed a love of nature that would make him a Hebridean orchid expert and begun a medical career that would take him from duties in bug-ridden city slums to a large country practice across East Lothian and, latterly, the idyll of Barra.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA polymath whose talents included ornithology, botany, Latin, Greek, elementary Gaelic, writing, painting and photography, not to mention a role as wine caterer during his time as a naval surgeon lieutenant-commander, he was born on the rather inauspicious date of 1 July, 1916 – the start of the Battle of the Somme and the bloodiest day of the Great War.

His father served as a medical officer during the conflict and his son, known as Jimmy, grew up at the family home and surgery, Ennerdale in Haddington, which he would eventually take over as a GP. Educated at Knox Academy before going to Warriston prep school in Moffat, he completed his schooling at the Edinburgh Academy, where his interest in bird photography began.

After going up to Edinburgh University where he started his medical studies in 1934, he was helping his father in the practice, while waiting to start as a house surgeon at Carlisle’s Cumberland Infirmary, when the Second World War broke out. He volunteered for the Royal Navy but completed his stint in Carlisle and another six months as a house surgeon at Edinburgh’s Deaconess Hospital before being called up in October 1940.

As a surgeon lieutenant-commander on HMS Ranpura he was initially attached to the Bermuda and Halifax Escort Force. The Ranpura, a former P&O passenger liner converted into an armed merchant cruiser, later took up duties on the North Atlantic Escort Force and worked the Indian Ocean.

In addition to his sick bay duties, as the junior doctor it fell to Robarts to be the ship’s wine caterer and keeper of the wine book detailing officers’ drinks bills. He also spent a great deal of time on cipher watch, censored the junior ratings’ letters and was in charge of the naval education department’s programme to provide further education on board ship.

By the spring of 1941 HMS Ranpura was on North Atlantic convoy duties, sailing from Halifax, Canada, to the south of Iceland, escorting the merchant ships keeping Britain and Russia supplied with thousands of tonnes of goods and equipment. They faced a constant onslaught from enemy U-boats and Luftwaffe air assaults and, on the morning of 7 May, 1941, the Ranpura was escorting convoy OB 318, comprising 36 merchant ships, when two were attacked. One, the Eastern Star, blazed from end to end and the other was paralysed. Robarts’ recollection, many years later, illustrated the barbarity of the Battle of the Atlantic:

“Shouts were coming from the Eastern Star and men could be seen jumping into the water. It was heartrending to hear the cries of the burned and injured crew. I hoped that they might be picked up by the rescue ship… sometimes no sooner had they performed their act of mercy than they themselves were torpedoed.”

But two days later the tables were turned in what became one of the best-kept secrets of the war. After another escort vessel spotted a U-boat, depth charges brought it to the surface. Then, as one of the destroyers, HMS Bulldog, prepared to ram the vessel, its crew abandoned ship. The rash move allowed a boarding party from Bulldog to capture the sub, U-110, and its equipment, including a naval Enigma machine and codebooks. The crucial find, swathed in the greatest secrecy, allowed Alan Turing and the Bletchley Park code-breakers to crack the German naval Enigma code, a superb intelligence breakthrough that changed the course of the war in the Atlantic.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOver the next year Robarts voyaged from the Clyde, via South Africa, to the Indian Ocean before returning to Scotland in 1944 where the Ranpura, lying off Invergordon, accommodated hundreds of marines training on the Moray beaches for D-Day.

After the war ended he returned to medicine, taking up general practice in 1946 when the life of a family doctor was all-consuming: morning, afternoon and evening surgeries followed by more house calls, often as much of a social welfare visit as a medical necessity, then home by 10pm to write up patient notes.

Pre-war he had trained in the slums of Edinburgh and Dublin but some atrocious housing conditions in Haddington were particularly shocking – attending a woman in labour he noticed an odd wallpaper pattern, only to realise it was alive with dozens of bugs.

In contrast, for several years he was official ship’s doctor on the National Trust for Scotland’s Gardens and Castle cruise around the British Isles – a welcome week-long break back on the water. On retiring in 1977 he and his wife Zoe moved to Barra, where he sailed and fished with his Orkney long-liner boat, part of his farewell gift from patients. He also worked as a locum doctor up and down the Outer Hebrides and thoroughly embraced island life, learning peat cutting and Gaelic and indulging his love of nature.

Robarts’ passion was wild orchids and he discovered the rare Irish Lady’s Tresses growing near his croft, prompting a 15-year botanical research study during which he cared for them as carefully as any of his patients. Botanists regularly visited his orchids and in 2005 he wrote the guidebook Orchids of Barra, revised in 2016. He also continued to be a keen ornithologist, able to identify birds by their song, and a fine landscape painter..

He and Zoe celebrated 70 years of marriage in 2015 following their permanent return to the mainland, having latterly spent the summer in Barra and the winter in Edinburgh. Although he missed the open vistas of the islands, he settled happily back in Edinburgh where he often visited the Botanic Gardens and used his vast general knowledge to tackle cryptic crosswords, amassing so many gold pen and dictionary prizes that he resorted to entering under friends’ and family’s names.

In his 80s he mastered a laptop computer to begin writing short stories for the newsletter of Edinburgh’s St Ninian’s Church, Comely Bank.

Latterly Robarts relished trips to his old stomping grounds of the Lammermuir Hills and East Lothian.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor his centenary his reminiscences, stories, photographs and paintings were compiled in a celebratory book One Hundred Years, reflecting the achievements of an exceptional life.

Predeceased in 2015 by his wife Zoe, whom he cared for over many years, he is survived by their daughters Jacqueline and Rosemary, son Philip, five grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

ALISON SHAW