Book review: The Way Of The Hermit, by Ken Smith with Will Millard

This is a most peculiar book. Let us start with the cover. The ostensible author, Ken Smith, also known as the Hermit of Treig, is first and foremost, but the collaborator or ghostwriter, Will Millard, is also acknowledged in a marginally smaller typeface. Smith has already been the subject of a Scottish BAFTA award-winning film, directed by Lizzie Mackenzie and described in the acknowledgements (by Millard) as “truly beautiful” and which “provided the inspiration to seek out Ken to write this book”. So I did wonder, more than once, why disrupt and disturb Smith, who by this account wants silence and the solitary over all? There is a strange passage towards the end where he says “I never imagined my words would make it into this book, or my photos into a film, but I hoped that the record I had kept of my life would one day form more than just a personal document for me to glance over every once in a while. I hope that doesn’t make me sound conceited”. There is a hint of humblebrag there.

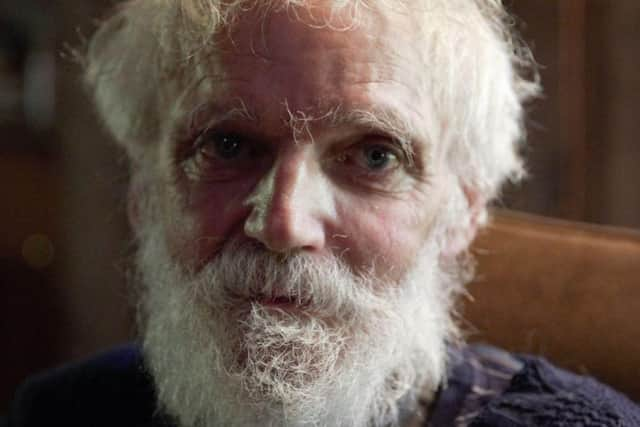

So: the bare bones. Smith was born in 1947 in Whatstandwell, Derbyshire, and as a young man went exploring in Canada and Alaska. He returned to an itinerant life, sleeping in bothies and under stars, until he managed to settle, somewhat, near Loch Treig, building his own cabin and taking work as a ghillie on the estate. He kept numerous notebooks and a camera, his one concession to modernity.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe book itself is a hybrid. The opening page has a kind of oral quality, such as daylight begging for “yer forgiveness”, “Aye, it’ll be getting”, “Yep. Put your faith in wood, not daylight”. (Why “yer” then “your”, I ponder). Later sections have “apologetic apostrophes” – “bloomin’” appears a lot – and words are italicised or capitalised for emphasis. But then there is the actual text from Smith, and not the ghost’s patina. It is an uneasy transfer. Here is Smith in his own words: “Little wood was within the bothy, but enough to light a small fire to reward I with a warming cup of coffee, a most desired drink to calm my motions and ache within my shoulders”. But then in other sections, the language strays towards the more effusive version of nature writing, such as “Do not forsake the beauty hiding in winter’s darkest hours though. When a full moon illuminates the snow, casting light on the white like a projector on an old cinema screen, there are wonders to behold”. I am categorically not saying Smith is incapable of uttering those sentences; I merely observe that there is a stark disjunction between the snippets and their frame.

Parts of the book are like good pub yarns. Did he encounter a supernatural presence in a bothy? I really couldn’t say, but he seems to have been shaken by it. Did he catch the biggest ever trout in Loch Treig? Maybes yes, maybes no. What is unusual is that some of the critical, even crucial moments are in a way glossed. Smith recounts being attacked by skinheads as a young man, and spending some time in hospital thereafter. Later in the book, he mentions almost as an aside the extent of the surgery he required. But what is missing is the why of this horrid incident, or even why the why is never raised. Was it sheer bad luck? Something that provoked someone? Class tensions? Being in the wrong pub at the wrong time? Whatever it was, the consequences were awful, and yet the story hangs in limbo, even though it seems to be the motivation to withdraw from the world.

Parts of this reminded me of a book I used to pore over with a friend: Whole Earth Catalog by Stewart Brand, a counter-culture manual that looked at self-sufficiency, ecology, different kinds of pedagogy and basically how to get away from the State and stick it to the man. So I now know from this book how to make wine from birch trees, but there is a serviceable Sauvignon Blanc in the village shop.

Being off-grid is fine, and is anyone’s individual choice, until you need the grid. The final section has the most of Smith’s own diary notes, after he had a stroke and was diagnosed with colorectal cancer. These are quite moving – he certainly feels caged in in an institution such as a hospital – but they do make a clear point. You might want your own private Walden, but a docken-leaf won’t cure all your ails. We do, as humans, rely on others.

The original hermits were the ones who “went into the desert” to be closer to God. In the final pages he says “I do believe in a heaven and a god, and I am a Christian… I have my own Christian beliefs and that’s that”. It is a perpetual dilemma: to be a recluse or to be a crusader? You can be good as a solitary, but can you do good as one? I suppose that any book that leaves you with more questions than answers is a good thing.

The Way Of The Hermit, by Ken Smith with Will Millard, Macmillan, £16.99