Teacher at remote school in off-grid Scottish Highland community takes a 'step back in time'

As teacher Claire Pepper safely arrived across the loch to see her new school, the boatman was paid in four cans of lager. After waving him goodbye, she started the half-hour walk up a track and across a field of wildflowers to the door of her new workplace, which was left unlocked.

For Ms Pepper, her arrival on the remote peninsula of Scoraig in the north-west Highlands, which is home to an off-grid community, proved to be one of her most inspirational postings yet.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

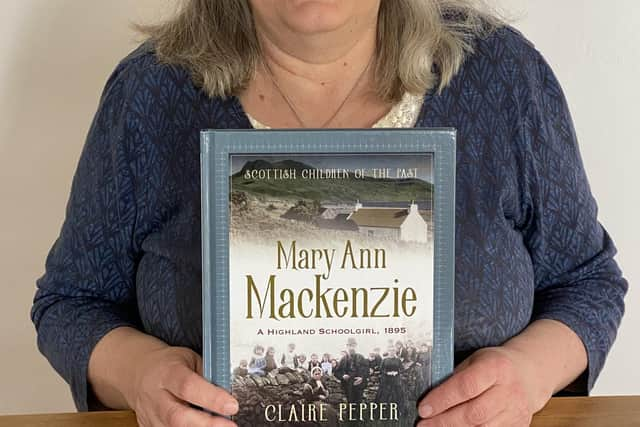

Hide AdHer year at Scoraig, which is home to around 70 people, led her to begin a new series of history books, written for the young reader in mind, called Scottish Children of the Past.

The first book, Mary Anne Mackenzie: A Highland Schoolgirl 1895, tells the story of a nine-year-old girl taught at Scoraig in the late 19th century, who sat in the very room where Ms Pepper led her class of initially just two.

"When I taught at Scoraig in 2014, some things had not changed since Mary Ann’s school days, including the high school-room windows, open fire places, and mice in the classroom,” Ms Pepper said.

The teacher’s time on the peninsula, she admitted, was challenging. She struggled with accommodation at first, living with no furniture apart from a couple of deckchairs. The weather meant that crossings over Little Loch Broom were often cancelled, leaving her at one point without access to a supermarket for six weeks. When she did get her shopping across the water, she ferried it home in a wheelbarrow, usually pushing against a headwind. Following the death of the school janitor, she had to clean and warm the school for several months.

Despite it all, Mr Pepper described it as a “wonderful” year where she had freedom to teach in a way that was best for her pupils and enjoyed the warmth and support of a community who threw her an afternoon tea in the bunkhouse, fixed her up a new home and rallied to fetch kerosene for the school generator when the classroom fell into cold darkness. At her previous school in the south of England, there was a bolt on the inside of the classroom door to keep the parents out.

She said: “When I arrived at the school and there was not even a lock on the front door, it just spoke of the trust of the community that I was about to live in – and it was wonderful.

“As you crossed the school threshold, it was like stepping back in time because there in front you were wrought iron stands with coat pegs on where the children for goodness knows how many decades had hung their coats on.

“The desks were quite old fashioned and up on the wall was a white glass cabinet full of encyclopaedias, which had been donated in 1908. And they were still on the wall.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe idea for the book series came on two fronts. With a long-standing interest in 19th-century education, Ms Pepper decided to organise a project on the ‘Victorian school day’. But when her resources arrived, not one book related to schools in Scotland or to Scottish pupils, except for a passing reference to use of the tawse.

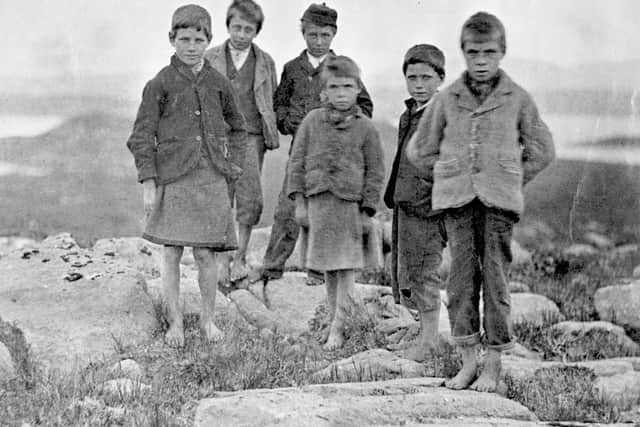

Meanwhile, discovering the school log book shed light on daily life at Scoraig – walking to school barefoot, mixing class with work on the croft and the punishments for speaking Gaelic in the classroom. Some of the challenges listed resonated decades later, Ms Pepper said.

“There were similarities – they ran out of coal in 1926, we ran out of kerosene in 2014,” she said.

While things changed at Scoraig over time, with its resident Gaelic-speaking community abandoning the peninsula in the 1960s as a new wave of residents seeking an alternative way of life arrived, it remains a place largely defined by its isolation, weather and geography.

Ms Pepper said: “When I was there, the youngest, who was five, walked three miles to school along the track. And the last bit of the journey was across the fields, which I think was a little bit taxing for her, although sometimes dad would give her a piggy back.”

Mary Anne Mackenzie was aged nine in 1895 and lived on a croft with her mother and four siblings following the death of her father, who drowned at sea in a storm.

She attended school with 30 other pupils, with the book illuminating everyday business of the Scoraig classroom. Poor attendance was noted at times of peat cutting with pupils arriving late due to the herding of cows. A ban on entering the school before 9am was lifted in 1908 so children could come in and shelter from the weather. School closures due to storms were also noted. Every day, pupils carried a brick of peat to help heat the school. A delivery of coal came by steamer.

Ms Pepper, who has now retired, received funding from The Strathmartine Trust and The Catherine Mackichan Trust to help towards the cost of publishing the book, with it now her “heart’s desire” to see it printed in Gaelic.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe next book in her series will be Jimmy and Ann – A Boy Miner and a Schoolgirl, Leadhills, 1841 will be published in November 2024 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of The Museum of Lead Mining in Wanlockhead.

"I just really wanted the children that I taught at the school, and children in Scotland more generally, to have a real appreciation of their heritage and their history,” she said.

Mary Ann Mackenzie- A Highland Schoolgirl, 1895 is available on May 1 from independent bookshops or online from www.scottishchildrenofthepast.com.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.