Scotland's seaweed eating ancestors who dined on the superfood more than 5,000 years ago

Today seaweed might have a reputation as a superfood, but "surprising” results of a new study of dental plaque taken from those buried 5,000 years ago suggest our ancient ancestors long valued the nutrient-rich offerings of the tide.

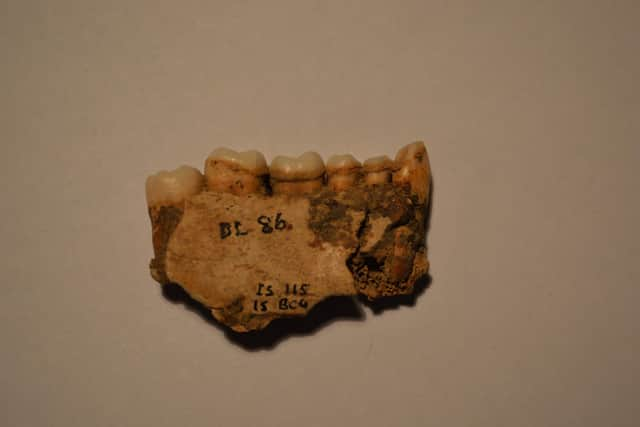

For thousands of years, those living in Orkney “widely consumed” seaweed as a key part of their diet, with teeth examined including those of a man aged between 40 and 50 and a younger male who could have been just 17 when he died.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSeaweed was also found to have been consumed by an individual found in Distillery Cave in Oban. Tests on those buried at inland sites in the Central Belt, including one at Juniper Green near Edinburgh, show people were eating freshwater plants, which might have included lily, to help sustain themselves during the Early Bronze Age period.

Previously, seaweed was thought broadly to be used for fuel, food wrappings and fertilisers, according to a study published in Nature Communications. Now this study shows seaweed remained “widely consumed” despite the advent of farming during the Neolithic.

Karen Hardy, professor of prehistoric archaeology at the University of Glasgow and principal investigator of the Powerful Plants project, started the analysis on remains left at the Tomb of the Eagles in Orkney. The Neolithic chambered tomb is located on a cliff edge at Isbister, South Ronaldsay, where bones of around 300 different people were placed around 5,000 years ago.

The remains have long helped illuminate life during the period and a civilisation beset by violence, disease and deformity.

Now, following test of dental plaque taken from eight individuals left at the tomb, evidence of diet has emerged. The results from the Isbister site have prompted a global investigation into seaweed as an ancient foodstuff in Europe, with the study spanning Lithuania, Spain, Portugal and France and a total of 74 individuals across 28 archaeological sites.

Prof Hardy said: “We began in Orkney at Isbister and had not really anticipated doing anything more than that, but when we got the results that we got they were so surprising and so definitive, we decided to expand the study.

"We went to the National Museum and got samples from Quanterness in Orkney and also sites in Central Scotland – and then we expanded internationally too. Seaweed was just not on the agenda at all. It is not part of a modern European diet, we don’t see it as a food, but it came out very, very strongly and on almost all the samples.

“We weren’t expecting it, it really surprised us. No-one has ever thought of seaweed before as a food in ancient Europe and I think that is what was really amazing to us. The reason we wanted to extend the study is that it was so consistent. We had it in almost every sample and we thought ‘gosh, there is something going on here’.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSea kale was also found to have been eaten by one of the individuals left at the Tomb of the Eagles.

A poem attributed to St Columba refers to the monks of Iona, a small island off the western coast of Scotland, collecting dulse, a type of red seaweed, off the rocks for food. It states: “Let me do my daily work/Gathering dulse/Catching fish/Giving food to the poor.”

Laws related to collection of seaweed in Iceland, Brittany and Ireland from the 10th century.

By the 18th century, seaweed was considered as ‘famine food’, including in the Scottish islands, and although seaweed and freshwater aquatic plants continue to be economically important in parts of Asia, both nutritionally and medicinally, there is little consumption in Europe.

There are about 10,000 different species of seaweeds in the world. However, only 145 species are eaten today, principally in Asia.

Researchers hope their study will highlight the potential for including more seaweeds and other local freshwater plants in our diets today, helping Europeans to become healthier and more sustainable.

Prof Hardy said: “Our study also highlights the potential for rediscovery of alternative, local, sustainable food resources that may contribute to addressing the negative health and environmental effects of over-dependence on a small number of mass-produced agricultural products that is a dominant feature of much of today’s western diet, and indeed the global long-distance food supply more generally.

“It is very exciting to be able to show definitively that seaweeds and other local freshwater plants were eaten across a long period in our European past.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCo-author on the paper, Dr Stephen Buckley, from the Department of Archaeology at the University of York, said “The biomolecular evidence in this study is over 3,000 years earlier than historical evidence in the Far East. Not only does this new evidence show that seaweed was being consumed in Europe during the Mesolithic Period around 8,000 years ago when marine resources were known to have been exploited, but that it continued into the Neolithic when it is usually assumed that the introduction of farming led to the abandonment of marine dietary resources.

“This strongly suggests that the nutritional benefits of seaweed were sufficiently well understood by these ancient populations that they maintained their dietary link with the sea.”

Seaweed is high in iodine, prebiotic fibre, antioxidants and plant protein, which naturally flourishes in Scotland given the clean, nutrient-rich waters and sheltered seas of sea lochs. Companies such as Mara Seaweed, which harvests in Fife, continue to push its virtues as a foodstuff and seasoning.

The country’s seaweed farming sector is growing at a healthy pace. A recent report suggested commercial-scale seaweed cultivation sector could generate over £70 million for Scotland annually by 2040. The raw material is used to replace resource-intensive products such as plastic, fuel and fertiliser.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.