Edinburgh Festival Fringe theatre reviews: 9 Circles | The Golfer | Afghanistan Is Not Funny | Salamander | Dedication | Pip Utton as Dylan

9 Circles ****

Assembly George Square Studios, until 29 August

As the war in Ukraine grinds on, with all its atrocities and pain, it’s perhaps time, once again, to look back at the west’s recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and to reflect on what we might have learned from them. Bill Cain’s 9 Circles, playing at George Square Studios in a taut and absorbing production by Guy Masterson, follows the journey through nine of circles of hell of a young US serviceman, Daniel Edward Reeves, who is discharged from the army which is his life, and eventually put on trial in the USA, for allegedly running amok in Iraq, and raping and murdering a desperate teenage girl, after killing her whole family.

It is a terrible story; and as Reeves moves through years of hell, passed from lawyer to lawyer, first in denial then swept by waves of self-disgust, betrayed by former comrades, and finally confronted with the ultimate horror of execution by injection, it’s part of Cain’s skill to keep the fact of his crime firmly in focus, along with his own suffering.

Advertisement

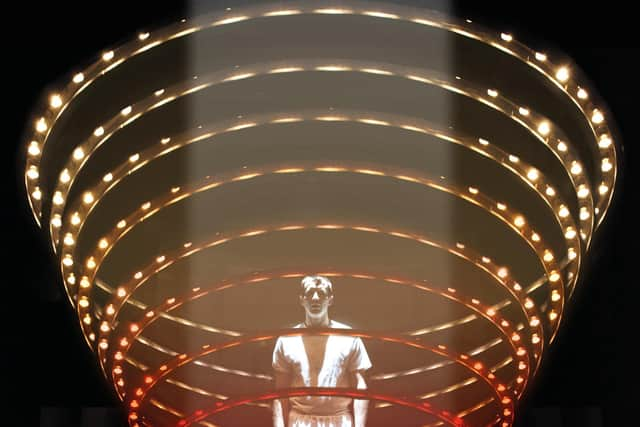

Hide AdOn a simple but powerful circular set by Duncan Henderson, lit by Tom Turner, Joshua Collins delivers a superb performance as Reeves, constantly in the spotlight, and undergoing a journey for which he seems desperately ill-equipped. He receives powerful support from David Calvitto and Daniel Bowerbank in a range of army and prison roles; and if the nine circles may seem one too many, for those unconvinced that anything but oblivion lies beyond Reeves’s painful death, this remains a powerful and well-crafted play about the damage war inflicts both on victims, and on those charged by the state to commit acts of violence, as their daily work.

The Golfer ***

Assembly George Square Studios, until 29 August

Playing alongside 9 Circles at George Square, The Golfer by two-time Scotsman Fringe First winner Brian Parks is a very different kind of American story; a piece of inspired absurdism involving an ambitious character called George who is struck by lightning while out playing golf, and transported into another dimension full of odd literary references, rich eccentrics, English aristocrats, and singing gonads detached from European castrati; “these guys are nuts”, he muses.

The show features a cast of six; and to say that its fast-moving comic dialogue often fails to land, in Edinburgh, is possibly to observe a cultural difference between off-Broadway New York and the Edinburgh Fringe, rather than any weakness in Park’s writing. In the end, though, George’s adventures in a world beyond the tedious demands of late-period capitalism seem more like an absurdist footnote to the 2022 Fringe, than a central piece of social comment; a vision just a shade too eccentric to hit home, where it really matters.

Afghanistan Is Not Funny ****

Gilded Balloon Teviot, until 29 August

On the Edinburgh Fringe, Henry Naylor is best known as a playwright and actor whose sustained concern with the world’s war zones and the west’s involvement in them has been a vital feature of the festival for the last two decades, shedding light on the victims of conflict, on the murky places of western policy that contribute to their suffering, and on the ambiguous and sometimes capricious role of British journalism in highlighting and sensationalising their plight, and then forgetting it again, for months or years.

He also, though, has another career as a well known writer of radio and television comedy for shows including Spitting Image and Dead Ringers; and in his new solo show Afghanistan Is Not Funny, which arrives in Edinburgh after award-winning runs in Adelaide and at the Hollywood Fringe, he brings together all these aspects of his life in a piece which tells the story of a trip he made to Afghanistan 20 years ago, along with photographer Sam Maynard, and which at one point – thanks to his comedy connections – almost became a film co-produced by Hugh Grant and directed by Stephen Frears.

Naylor’s story of media complicity and voyeurism in the tragedy of Afghanistan is more complex and unresolved than those which shaped some of his earlier plays; and it’s sometimes tempting for the audience to focus on his satire on London media life, rather than on the tragedy at the show’s heart. There are moments in his writing, though, that simply arrest the soul, particularly as he describes a strange encounter in a refugee camp outside Kabul; and as betrayed Afghanistan once again falls under Taliban rule, Naylor’s show provides a vivid and necessary reminder of the west’s profound complicity in a tragedy we have no right to forget.

Salamander ****

Greenside @ Riddle’s Court, until 27 August

Advertisement

Hide AdThe place is Leith, the year is 1983; and after the murder of a local prostitute, Lothian Police have sent in a woman police inspector to try to get to know the women working on the streets in the area, and to find out what can be done to make them more safe.

Mhairi McCall and Cal Ferguson’s new musical Salamander – playing this week only, at Greenside in Riddle’s Court – therefore opens in a local church hall, where working girls Tiff, Violet, Candy and Roxy have come along to meet policewoman Pat and a church volunteer called Joan, who provides tea and home-made tray-bakes.

Advertisement

Hide AdWith occasional pauses for powerful and pointed songs, the women slowly begin to understand one another, as the apparently hard-as-nails prostitutes open up about their problems and fears, and cast a new light on the state of Joan’s miserable traditional marriage; and if the Leith of 40 years ago seems a distant place now – the area is now less mixed and more fully gentrified, and the business of prostitution has largely moved online – there’s still something timely and recognisable, in the age of #MeToo, about a group of women from very different backgrounds gradually learning how much patriarchal attitudes shape all of their lives.

Mhairi McCall delivers a memorably complex and beautifully sung performance as Tiff, a young teenage prostitute who loves to write poetry despite a dangerous drug habit; and Claire Docherty is memorable as a hard-bitten older street-worker who takes Tiff under her wing. At its heart, though, Salamander is a powerful and fast-moving ensemble show, full of the energy generated by a six-strong female cast – plus on-stage guitarist Lewis Lauder – working brilliantly together; and creating a funny, powerful and poignant tribute to the full dignity and humanity of women whose way of life is still often stigmatised and “othered”, 40 years on.

Dedication ****

Greenside @ Nicolson Square, until 27 August

Born in the USA in the early 1960s, Roger Peltzman is a New Yorker who spent most of his childhood and youth knowing little or nothing about his mother’s past, as the only member of her Jewish family to survive the Nazi holocaust. Like many survivors, she preferred not to talk about it; and it wasn’t until after her death, in the late 2000s, that Peltzman began to piece together the little he did know, and seriously to research his family history.

By that time Peltzman had moved on from early flirtations with many interests, musical and otherwise, to pursue a growing passion for classical music, and for his career as a pianist; a transition that drew him into an ever more urgent quest for a sense of connection with his uncle Norbert Stern, his mother’s elder brother, a hugely gifted and acclaimed young pianist who was studying at the conservatoire in Brussels – where the family were living – when he and his parents were arrested and sent to their deaths in Auschwitz.

In a sense, this is a familiar story of Europe’s most horrifying genocide; but Peltzman’s one-hour solo show is put together with such grace, beauty and sorrow that it offers a richly rewarding and thoughtful experience. There are powerful visual images of Peltzman’s lost family, of the Brussels streets where they lived, and of the Conservatoire where Peltzman is finally able to play on the same stage as Norbert; there are reflections on the growing evidence that trauma as profound as that of the holocaust can be passed down generations, through our very DNA.

And at key moments during the show, Peltzman takes to the grand piano on stage, and plays like an angel, connecting us profoundly both to a lost European past and to our living present; not least through the music of Chopin, the composer Norbert Stern loved best, and through whom he sometimes seems to communicate with his living nephew, even today.

Pip Utton as Dylan ***

Pleasance Courtyard, until 29 August

Advertisement

Hide AdThere’s something subdued about Pip Utton’s performance in this new monologue, set just before a concert advertised – accurately or not – as Bob Dylan’s final live appearance. In a sense, the muted tone is hardly surprising; Dylan is now over 80, and has never been fond of grandstanding in public about his life, times and music. Utton’s performance is also burdened with a truly distracting black curly wig, which somehow seems more obtrusive than any headgear worn by Dylan himself; and the result is a low-key performance with a slightly provisional air, more like an initial tryout than a full production.

What the show does boast, though, is a glorious 55 minute script by multiple Fringe First winner John Clancy, brooding powerfully on Dylan’s influences, the pattern of his career, and his relationship with his own fame, in a profoundly American story that meshes deeply with 20th century history, but also has searching things to say about the complex relationship between the artist and his work. Utton is word perfect as ever in leading us through Clancy’s text; and although I hope to see a more dynamic and vivid version of this play one day, Pip Utton as Dylan remains a rewarding show, for those who care about the work of one the great poet-songwriters of the last 60 years.